Tuberculosis Glamour

Tuberculosis, once a deadly scourge in 18th and 19th century Europe, was wrapped in an unlikely shroud of beauty and allure by artists, poets, and society itself. In an era ravaged by the disease, the sickly pallor and emaciation it caused were perversely idealised as traits of ethereal beauty and fragile femininity. This odd reverence can be traced back to influential figures and artworks of the time, who, perhaps unconsciously, wove the symptoms of the illness into the Victorian beauty ideal.

Henry Peach Robinson's photograph "She Never Told Her Love" from 1857, shows a serene girl in repose, untouched by the visible agony that tuberculosis wrought. This divergence from reality into a more palatable narrative illustrates the period's readiness to overlook the grim realities of the disease for an aesthetic idealisation. Such depictions mirrored a widespread fascination with a 'consumptive chic' that infiltrated fashion and popular culture.

It wasn't merely about looking the part. François Gregoire & Co. capitalized on this obsession by marketing products in 1866 that promised the sought-after pallor, disregarding the health implications of using poisonous substances for skin whitening. Similarly, the beauty routines of the era, involving arsenic wafers and toxic enamels, underline a societal commitment to achieving an ill-fated aesthetic at any cost.

In literature and opera, the theme persisted with characters like Violetta from Verdi's "La Traviata" (1853), who embodied the tragic yet romanticised figure of the consumptive woman. Her death, emblematic of the era's conflicted relationship with tuberculosis, presented a poignant mix of despair and desirability, casting the disease in an alluring light.

This romanticisation wasn't confined to fictional narratives. Known figures, like Charlotte Brontë, echoed these sentiments, calling consumption a "flattering malady," despite its fatal nature.1 The intermingling of tuberculosis with concepts of beauty demonstrates a troubling interplay between disease and desirability in Victorian society, challenging our modern perceptions of health and attractiveness.

"Beata Beatrix" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, painted roughly between 1864 to 1870, captures this macabre fascination by presenting the illness not just as a condition but as a transformative state, imbuing the afflicted with a luminous, albeit somber, grace. Beyond mere individuals, tuberculosis shaped an entire aesthetic mode, affecting fashion trends that embraced corsetry to mimic the disease's thin likeness and celebrated pallor over health.

John Singer Sargent's "Madame X" (1884) encapsulates the era's vanity and its dark undercurrents. The painting scandalised society not because it brazenly displayed the implications of such beauty norms but due to its sexual implications. It symbolizes the broader historical oblivion to the deadly implications of such romanticised concepts of health and beauty.

The enigmatic allure of tuberculosis in the Victorian era illustrates a complex legacy where morbidity entwined with beauty standards. This historical narrative highlights a time when the glamourisation of sickness masked the grim realities of tuberculosis. It speaks volumes about Victorian society's capacity to romanticise even the deadliest conditions for the sake of maintaining an aesthetic ideal.

Aesthetic Movement

The Aesthetic Movement, flourishing in the latter half of the 19th century, emerged as a buoyant counter-current to the industrial grimness and moralistic norms of Victorian England. It championed 'Art for Art's Sake,' detaching art from didactic conventions and societal obligations, and injecting into the Victorian ethos a fresh conceptualisation of beauty. This movement was not just a passive escape from reality but a radical reimagining of how art and beauty interacted with life.

Central to the movement were trailblazers like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris, whose creative output fundamentally challenged and reshaped Victorian ideals of beauty. Rossetti, with his richly-hued canvases and ethereal depictions of women, untethered feminine beauty from its traditional Victorian bonds, showcasing a heightened, almost otherworldly allure. His works, such as "Proserpine" and "The Day Dream," epitomized the Aesthetic creed, extolling beauty and sensuality unmoored from moral or narrative constraints.

William Morris shared Rossetti's commitment to beauty, but his influence expanded beyond the canvas into the very fabric of Victorians' daily lives. With an encompassing view of art that included architecture, furniture, and even poetry, Morris advocated for beauty that was not only to be admired but lived with. His designs for wallpapers and textiles drew on natural forms and medieval craft, embodying the Aesthetic Movement's penchant for blending inspiration from various eras and cultures. Through his work, Morris offered an alternative to the ornate clutter common to Victorian homes, arguing instead for simplicity, functional use, and intrinsic beauty.

The rallying cry for art's sake led to an interesting paradox; while eschewing didacticism and utility in one sense, the Aesthetic Movement managed to influence society very directly—by transforming notions of beauty and decorum in public and private spaces. The embrace of Eastern influences, particularly Japanese art, further expanded the Victorian aesthetic palette, inspiring a more minimalist elegance that contrasted sharply with the period's earlier preferences.

As the movement swelled, its philosophies trickled into the fabric of Victorian life, becoming not just an artistic stance but a broader social phenomenon. Vernon Lee, a follower in the Aesthetic tradition, perceptively noted that this devotion to beauty might shallowly skim the surface of life without underpinning deeper values or critiques.2 Yet, even so, this pursuit of beauty for its own sake had an undeniable impact—softening rigid class distinctions by uniting connoisseurs and public alike under the shared banner of art appreciation.

The Aesthetic Movement stands as a pivotal era that did more than challenge contemporary notions of beauty. It redefined the interplay between aesthetics and utility, presaging modernist movements that continued to explore and elevate 'Art for Art's Sake'. Its legacy touches upon the evocative power of art to transcend temporal concerns, cementing its place in the comprehensive narrative of Britain's artistic heritage and its ongoing discourse on beauty.

Female Representation

The Victorian era was marked by a palpable dichotomy in the representation of women, reflecting a broader societal rigidity. Artists both celebrated and constrained feminine beauty, crafting images that resonated with idyllic virtue while simultaneously reinforcing the gender norms of the time. This portrayal highlighted the pedestal of female beauty; however, it also served to underscore the limitations placed on women within the public and private spheres.

Artworks from this period frequently depicted women as embodiments of purity, sensuality, and domesticity, a reflection of the Victorian mindset which extolled women's roles as caregivers and moral beacons for the family. Paintings such as Frederick Leighton's "Flaming June" and Edward Burne-Jones's series on the "Briar Rose" enchant with their romanticized, languorous portrayals of feminine beauty. These works underscore a prevalent idealisation; women are to be admired, the object of the male gaze, yet their portrayal remains confined within the bounds of passivity and decorum.

This idealisation of female beauty in Victorian art often glossed over the harsher realities of women's lives during this period. Behind the canvas and gilded frames lay a narrative far removed from these depictions—of women campaigning for their rights, managing households in the absence of men-folk seeking fortunes, and contributing to the literary and reformist fabric of society. Artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who famously painted powerful yet ethereally beautiful women, wavered between reality and idealisation. His models and muses were not mere vessels of pictorial allure but were often strong-willed and independent individuals, like Elizabeth Siddal, who was an artist in her own right.

The critique and celebration of womanhood surface through subtler, more nuanced representations too. The 'fallen women' depicted in Pre-Raphaelite works – from Rossetti's 'Found' to Augustus Egg's 'Past and Present' – delve into the consequences of societal neglect and moral judgment, offering a counter-narrative to the glorified domesticity of Victorian womanhood; they unmask beauty to expose the societal costs of maintaining such ideals.

Moreover, the contrast between these idealised representations and the lived experiences of women sparked an undercurrent of discomfort—raising questions about the narratives celebrated in Victorian art. Activists and writers like Mary Wollstonecraft and later, suffragettes chafed against these glorified constraints, pushing for representation that mirrored women's evolving roles and realities.

In the intimate details of drapery, the reserved postures, and even the choice of subjects themselves, Victorian art evokes a tension between beauty as an abstract ideal and the functional confines of gender norms. As much as these artworks immortalize certain standards of beauty, they equally serve as mirrors reflecting a society grappling with its own contradictions and change.

The idealisation of female beauty in Victorian art overlaps with societal expectation, leaving echoes that questioned and shaped the evolving narrative of women's emancipation. While these works offer a study in contrasts—between celebrated ideals and stark realities—they nonetheless contribute a vital dialogue to the ongoing discourse concerning gender, representation, and identity.

The depiction of women in Victorian art serves as a compelling lens through which to explore the tension between societal norms and the burgeoning dialogue on gender equity—a narrative woven in the strokes of Victorian brushes yet resonating far beyond its era.

Art vs. Morality

In the labyrinth of Victorian art, every brushstroke and chisel mark more than merely crafted beauty; they sculpted contentious conversations between aesthetic pursuits and moral imperatives. This era's artists found themselves at the crossroads of an age-old debate: Can art exist purely for beauty's sake, or must it bear the burden of moral messaging? The tension this question stirred within Victorian society is emblematic of a period characterized by its strict moral codes and an insatiable appetite for beauty.

Artists like James McNeill Whistler and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood stood defiant in the face of this question, challenging the conventional wisdom that art must serve as a vehicle for moral education. Whistler's "Nocturne" series is a quintessential champion of the 'Art for Art's Sake' movement, presenting ethereal landscapes that eschew narrative for a celebration of form and color. His infamous libel trial against John Ruskin, who had accused Whistler of "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face," epitomizes this clash between aestheticism and moralist art criticism.3 In defending his work, Whistler argued for the artist's right to pursue art that delights the senses without conferring didactic lessons, positing beauty as an autonomous entity.

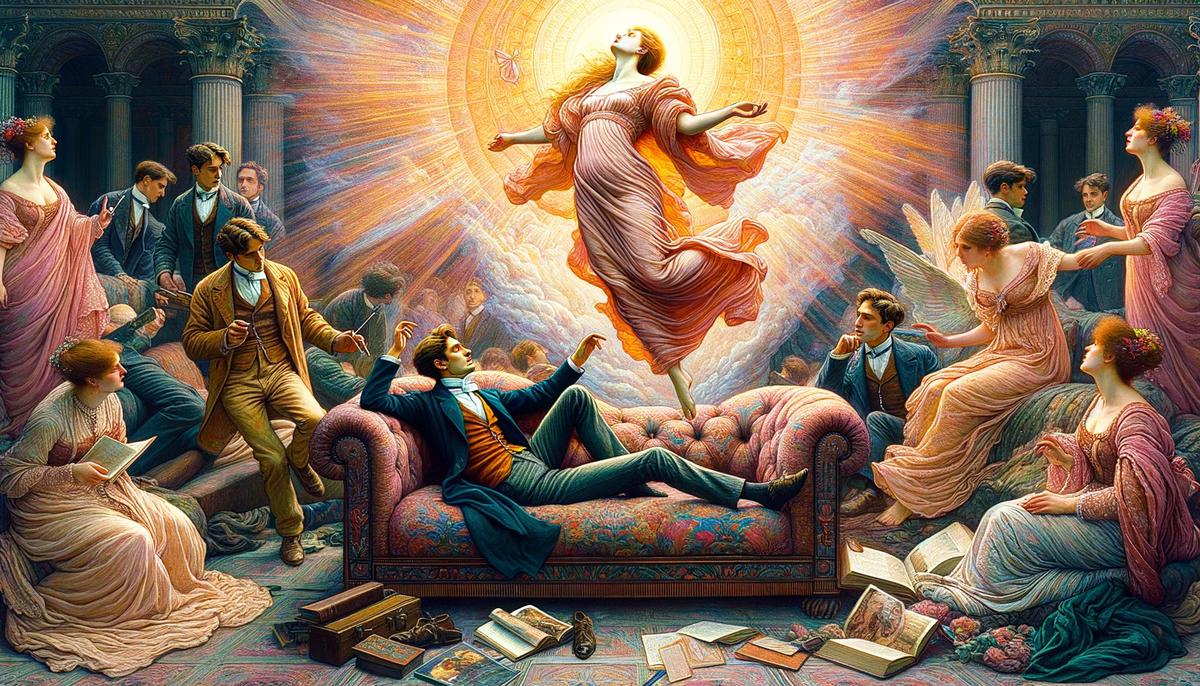

Conversely, the Pre-Raphaelites, while equally committed to artistic beauty, did not shy away from embedding their works with strong moral undertones. Their meticulous attention to detail and vibrant colors captivated viewers, but beneath the surface lay a critique of societal norms and a veiled yearning for reform. Ford Madox Brown's "Work," beyond its visual allure, provides commentary on the division of labor and the nobility of toil in an industrial age. Similarly, William Holman Hunt's "The Awakening Conscience" portrays a woman rising from her lover's lap, an illuminating moment of moral reckoning and spiritual enlightenment beneath its visually stunning surface.

The negotiation between art and morality often materialized in subtler, more private forms. Domestic art began to serve as an unspoken moral compass for the Victorian household, embodying ideals of purity, family bonds, and piety in aesthetically pleasing forms. The fusion of aesthetic beauty with symbols of moral righteousness within one's home acted as subtle reinforcements of societal values, blending visual pleasure with ethical guidance.

Furthermore, the exhibition spaces of Victorian England underscored this tension between the aesthetic and the moral. The Royal Academy was often criticized for maintaining rigid stances on moral respectability, making the Grosvenor Gallery and later venues like the Savoy Chapel preferred sites for artists seeking to escape such constraints.4 These alternative spaces became sanctuaries for the beauty-first philosophy, showcasing works that prioritized aesthetic innovation over moralistic narratives, thus broadening the public's exposure to art that defied conventional expectations.

Victorian art's oscillation between beauty and morality elucidates the complex tapestry of societal values, personal convictions, and artistic liberties of the time. As much as these polarities created friction, they also fostered a rich dialogue that propelled Victorian art into new realms of expression. The works birthed from this dynamic not only decorate galleries but also narrate a pitched battle for the soul of art—a battle waged in the studios, salons, and dining rooms of Victorian England.

In reflecting on this era, it becomes clear that such tensions never truly abate. They morph and resurface across generations, reminding us that art's beauty often lies in its capacity to question, to challenge, and to inspire discourse—not merely in its alignment with or defiance of societal mor