(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1834

Died: 1896

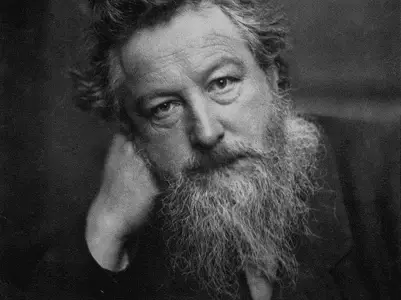

Summary of William Morris

William Morris was one of the most influential artists of the second half of the nineteenth century, influencing the art, culture, and politics of the time. Before abandoning both to work with the Pre-Raphaelites on his visions of mediaeval arcadia, he trained as a priest and then an architect before switching back and forth between the two throughout his career. Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti influenced his early work, but he soon moved into architecture and interior design, creating some of the most enduringly popular and commercially successful textile patterns in British art history. At the end of his life, Morris concentrated on the radical political ambitions that had always been at the heart of his practise, publishing utopian socialist fantasy literature, and consolidating his lifelong work as an author and poet. It is impossible to overstate the importance of his work in shaping the next century’s artistic, architectural, and political landscapes. He died in 1896.

Many consider William Morris to be the forefather of the worldwide Arts and Crafts movement. For him, the Middle Ages’ idealised craftwork and cottage industries were a utopian vision of what was possible in the modern world. According to Morris, art could not exist without being the result of a collaborative effort that was imbued with the spirit of community and a deep sense of connection to the natural world. From Art Nouveau to Futurist and Dadaist artists’ books, Morris’ arts and crafts aesthetic was an important influence on a wide range of artistic and literary movements in the following decades.

He was the first artist of the modern era to combine words and images to express his ideas. Morris developed an aesthetic in which the words printed on a hanging tapestry or in a hand-printed manuscript, for example, are as dependent on their surrounding pattern-work for meaning as the images are on the text, following in the footsteps of that other great London-born radical and luminary, William Blake. From Constructivist book design to Concrete Poetry, the more overtly radical experiments in art and language of the twentieth century were influenced by this idea of a multi-media art practise.

Friends and creative collaborators who shared his artistic and spiritual worldview were William Morris’ preferred method of working. As a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Morris was part of a group of artists who shared a belief in the importance of collective endeavours, like those of the Brotherhood’s members. Morris and his fellow avant-gardists certainly fit the bill if the term avant-garde is defined as a radical, collective aesthetic vision infused with utopian political goals.

Childhood

The third of nine children, William Morris was born in Walthamstow, Essex, in 1834. Because of a wise investment in the Devonshire mining company to which William’s father belonged, his family was able to enjoy an upper-middle-class lifestyle. His father, William Morris Sr., died at the tender age of 13, but his fortune allowed the artist to enjoy a comfortable life well into his adulthood.

Morris grew up in a large country house near Epping Forest in Essex, which was surrounded by ancient woodland and mediaeval architecture. When he was sent to Marlborough College in Wiltshire to attend high school, he boasted that he had “learned next to nothing” In place of doing schoolwork, Morris read, followed his own interests, and explored the surrounding area, which included ancient ruins, mediaeval churches, and even a Neolithic settlement. Morris’ early letters, written when he was just fourteen years old, reveal a passion for architecture and a keen eye for design. Morris would carry the memories of his childhood with him throughout his life, informing his design work and serving as nostalgic touchstones in his writing.

Early Life

Morris enrolled in Exeter College, Oxford, in 1853 to pursue his mother’s dream of becoming a priest. Since that time, his reading in the library has changed dramatically: from religious matters to history and ecclesiastical architecture to the art criticism of John Ruskin, his outlook on life has dramatically changed. While attending the same university as Edward Burne-Jones, a budding artist and designer who would go on to be one of his closest friends for the rest of his life as well, he discovered poetry writing, and that was that. Charles Faulkner and Richard Watson Dixon were part of a group of Oxford undergraduates known as the Birmingham Set, which shared an interest in theology, medievalism, and Tennyson’s poetry.

At the age of 21, Burne-Jones moved to London to pursue a career as a painter and stained-glass designer, while Morris changed careers to become an architect, a decision that his family did not approve of. Morris, on the other hand, decided to begin an apprenticeship in the pursuit of his dreams. When he met Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his career took a new turn. Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais formed this close-knit group in 1948, but it had disbanded two years earlier. Rossetti’s meeting with Morris and the creation of a new creative triumvirate with Burne-Jones would have far-reaching effects on British art in the years to come. A wave of artistic creativity washed over Morris, and he found himself among painters whose subjects included nature and mediaeval knighthood. Morris had fought for these principles since he was a child, and now he had the opportunity to put them into practise with others. Because of the influence of Rossetti and Burne-Jones, Morris decided to forgo a career as an architect and instead focus on painting in the Pre-Raphaelite tradition.

Mid Life

Even though Morris’s paintings never received the same critical acclaim as those of his Pre-Raphaelite peers, he embraced the bohemian lifestyle of the group and painted long-haired mediaeval women in natural settings similar to those depicted in Rossetti’s watercolours. They returned to Oxford in 1857 to decorate the Union Library’s walls with murals by Morris, Rossetti, and Burne-Jones. Jane Burden, a beautiful, working-class girl, began to model for Morris and Rossetti’s paintings in the year that Morris met her. They were married in 1859 after Morris fell for her.

Morris’s creative imagination began to take him beyond painting at this time. Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics and ethics, including a love of nature, mediaeval aesthetics, and Gothic architecture, as well as a dislike of mechanisation, interested him. At the same time, he longed for a place outside of the city where he could start a family and raise a family. Red House, a collaboration with Gothic architect Philip Webb completed in 1860, was the culmination of these aspirations. The Red House is a work of art that epitomises the Arts and Crafts movement. As the Pre-Raphaelite artists had defined in their paintings the new paradigm of beauty, the Arts and Crafts movement realised these ideals in three dimensions, typifying the new paradigm with its sloping gabled roofs, painted brick fireplaces, and meandering cottage gardens. Located just outside of London, Morris’s artistic associates made Red House their country retreat for the next five years.

Many of the principles of Arts and Crafts interior design were established by Morris and his friends after the house was completed, through their creative collaboration. The stained-glass windows were designed by Burne-Jones, while Morris collaborated with Rossetti and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle to create the murals. He turned his attention to wallpaper and textile design around this time, and some of these designs still remain in the home. Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. was founded as a result of this collaborative effort and is now known as ‘The Firm,’ an art and design firm that promotes traditional methods and handicrafts with a strongly medievalist aesthetic. P.P. Marshall and Charles Faulkner were also members, along with Rossetti, Webb and Burne-Jones.

The company established a presence in London and soon began to see significant growth in its bottom line. However, Morris’s personal fortunes began to deteriorate around this time, and he was forced to sell Red House in 1865, despite the fact that it was inconveniently located far from the Firm’s London headquarters. Despite the fact that he and Jane had lived happily at Red House for some time with their two daughters, Jane had recently begun an affair with Morris’s friend and mentor Rossetti. During the 1860s, Morris became one of England’s best-known poets thanks to his dedication to hard work and metered verse. In 1871, he and his family moved to a country house in Oxfordshire called Kelmscott, where they were joined by Rossetti. When Rossetti arrived at Kelmscott, Morris was said to have allowed him to join them because he was concerned about his wife’s well-being. However, the domestic situation caused friction between the two, and Rossetti eventually left in 1874.

Late Life

When Morris founded Morris & Co. in 1875, it was nearly 50 years after he had disbanded The Firm that the firm would continue doing business. A British fabric and wallpaper company purchased the design rights to Morris’s designs after his company was liquidated in 1940. Morris’s designs are still sold under his name to this day. In an unprecedented expansion of floral wallpaper and fabric designs, he developed a mercurial inventiveness that fueled the company’s success. He immersed himself in the design process, immersing himself in the theory and practicality of the design process. To express his admiration for the past’s art, he helped found the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings, a group that opposed the restoration of historic structures using modern methods. The anti-scrape movement is alive and well today, and the ideas that underpin it are now widely accepted.

Morris was also becoming more socially aware at this time. Prior to this, his views on craftsmanship and opposition to modern industrial methods had already pushed him toward progressive movements. Morris, on the other hand, became a radical socialist after seeing the stark inequalities of class in Europe and learning more about current politics. The utopian socialist fantasy travelogue News From Nowhere (1890) was one of his many popular works related to his cause. He also founded the Socialist League in Hammersmith, West London, where his family had relocated in 1879. Morris’ political views were inseparable from his aesthetics, just like John Ruskin’s undergraduate hero, Morris. The products of artistic labour should be returned to the working classes, according to his philosophy.

Morris died at his new home in West London, which he named Kelmscott House in homage to his former country estate in the county of Buckinghamshire. Kelmscott Press, his final creative venture, was established in 1891. He had long been fascinated by mediaeval ecclesiastical manuscripts, which he drew inspiration from when he decided to start his own publishing house to produce beautiful, illustrated books. After that, he spent most of his time between Kelmscott Press, his design work, and his socialist activism until his death in 1896.

William Morris has left behind a legacy that is as vast as it is difficult to track down. Art, architecture, design, poetry, and political thought were rocked by his artistic and poetic prowess, as well as the radical new ethos on art and society he advocated.

The Arts and Crafts Movement, of which he is widely regarded as a founding father, was his most visible legacy. Art Nouveau and the North American Arts and Crafts Movement were both influenced by his work, as well as by a number of friends and acquaintances of his including his daughter May Morris, who took up his slack.

‘The Firm’ and the building of Red House were examples of his vision of an artistic community based on cooperative, artisanal work. Morris’s ideals of combining beauty and function through design and decorative lettering would soon be carried forward by Eric Gill, who founded his own Catholic arts circle in Sussex. Some decades later, the 1951 Festival of Britain was inspired by Morris’s socialist beliefs and his understanding of the role of the community in artistic production, introducing these principles to a new generation of creatives such as Terence Conran and Lucienne Day. Avant-garde art’s golden age in the early twentieth century can be traced directly back to William Morris’s utopian collectivism.

Furthermore, Red House’s architectural and decorative unity had a lasting impact on architectural philosophy, influencing the way buildings were conceptualised and designed for many decades to come. It was Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who built his buildings as a “total work of art,” with interior design, furniture and architecture all working together as a cohesive whole. Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Gropius, two modernist masters known for their sleek and refined designs, both acknowledged the influence of Morris’s work on their early careers. There is a sense of Morris’s thoughts on how to combine country and city in Welwyn Garden City, an early twentieth-century project that exemplifies the socially egalitarian concept of the Garden City.

Morris continues to serve as an inspiration to many modern artists. David Mabb, for example, has said that Morris’s work is both a contrast and a compliment to much twentieth-century art’s production methods and political ethos.

Famous Art by William Morris

La Belle Iseult

1858

The only easel painting by Morris that has reached this level of near-completion and is a quintessential work of Pre-Raphaelite-era portraiture, despite the fact that it has been listed as ‘unfinished’ since its creation. Jane Burden, Morris’s soon-to-be wife, was the model for the painting, and it is widely believed that he began working on it during their courtship. During the composition process, the artist reportedly struggled with the human body’s proportions, which he was never able to achieve as effectively as his peers. “I cannot paint you, but I love you” is said to have been written on the back of the painting when he finished it.

Red House

1860

Philip Webb, the architect who collaborated with Morris on this project, is widely regarded as Morris’ crown jewel. His dreams of mediaeval romance and collaborative creativity were realised in the country home Morris built for the family following his marriage to Jane. Red brick construction with pointed arches, Tudor gabled roofs, and turrets from mediaeval fairy tales resulted in a strange and magnificent red brick structure. For Rossetti, the house was “more a poem than a house” and not just a place where he lived.

Green Dining Room

1868

One of three refreshment rooms built for the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) in the 1860s, the Green Dining Room (also known as the Morris Room) is an example. Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., the firm known as The Firm, received this commission, not just Morris. Since the establishment of The Firm in 1861, Morris and his collaborators had enjoyed considerable critical and commercial success. Morris, Philip Webb, and Edward Burne-Jones were the main players in this project. In keeping with their previous joint endeavours, they each focused on the parts of the room that suited their particular strengths. That spirit of collaborative artisanship has been embodied in the Green Dining Room.

Strawberry Thief

1883

One of Morris’s best-known decorative textile designs, Strawberry Thief took Morris months to perfect before he was able to successfully print it. The artist envisioned the fabric being used as a medieval-inspired wall hanging or as a curtain. The design, on the other hand, was inspired by the thrushes that would raid his country kitchen at Kelmscott Manner and thus infused with sentimentality. Although the foliate patterns are intricate and striking, there is little separation between the foreground and background, so the birds remain the design’s most prominent feature due to their light colouring and realistic renderings. They also serve as the mischievous protagonists of a storey that plays out on the fabric’s surface, entertaining with their song while stealing the precious berries.

Woodpecker Tapestry

1885

Artists like Philip Webb and Edward Burne-Jones collaborated on many of Morris’ most well-known tapestry designs. For his Woodpecker Tapestry design, his imagination and technical ability are all that are required. Originally intended for a billiard room in London, the three-meter-tall piece was conceived on a grand scale. Morris’ poem “Verses for Pictures” was later published in Poems By the Way (1891) as an inscription on two scrolls above and below an image of a woodpecker and a songbird perched in a tree. “I once a king and chief/ now am the tree bar’s thief/ ever twixt trunk and leaf/ chasing the prey” To punish King Picus for rejecting her advances in sexual relations, the sorceress Circe casts a spell that turns him into a woodpecker, as recounted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer now Newly Imprinted

1896

The Kelmscott Chaucer is a well-known example of Morris’ final major artistic endeavour, the Kelmscott Press, and one of its most important products. Morris had been translating and illustrating mediaeval stories for more than two decades, and he had given several hand-made manuscripts to family and friends. It took him months of research and scouting to find the perfect handmade papers, woodblock carvers, and typefaces for his Kelmscott Press, which opened its doors in 1891. After initially selecting a medieval-style typeface to represent Kelmscott Chaucer, it was decided to create an entirely new typeface called “Chaucer” for the project.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- William Morris was one of the most influential artists of the second half of the nineteenth century, influencing the art, culture, and politics of the time.

- Before abandoning both to work with the Pre-Raphaelites on his visions of mediaeval arcadia, he trained as a priest and then an architect before switching back and forth between the two throughout his career.

- Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti influenced his early work, but he soon moved into architecture and interior design, creating some of the most enduringly popular and commercially successful textile patterns in British art history.

- At the end of his life, Morris concentrated on the radical political ambitions that had always been at the heart of his practise, publishing utopian socialist fantasy literature, and consolidating his lifelong work as an author and poet.

- It is impossible to overstate the importance of his work in shaping the next century’s artistic, architectural, and political landscapes.

- He died in 1896.Many consider William Morris to be the forefather of the worldwide Arts and Crafts movement.

- For him, the Middle Ages’ idealised craftwork and cottage industries were a utopian vision of what was possible in the modern world.

- According to Morris, art could not exist without being the result of a collaborative effort that was imbued with the spirit of community and a deep sense of connection to the natural world.

- From Art Nouveau to Futurist and Dadaist artists’ books, Morris’ arts and crafts aesthetic was an important influence on a wide range of artistic and literary movements in the following decades.

- He was the first artist of the modern era to combine words and images to express his ideas.

- Morris developed an aesthetic in which the words printed on a hanging tapestry or in a hand-printed manuscript, for example, are as dependent on their surrounding pattern-work for meaning as the images are on the text, following in the footsteps of that other great London-born radical and luminary, William Blake.

- From Constructivist book design to Concrete Poetry, the more overtly radical experiments in art and language of the twentieth century were influenced by this idea of a multi-media art practise.

- Friends and creative collaborators who shared his artistic and spiritual worldview were William Morris’ preferred method of working.

- As a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Morris was part of a group of artists who shared a belief in the importance of collective endeavours, like those of the Brotherhood’s members.

- Morris and his fellow avant-gardists certainly fit the bill if the term avant-garde is defined as a radical, collective aesthetic vision infused with utopian political goals.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.