Vincent van Gogh's artistic journey was profoundly influenced by various elements, ranging from literature and Japanese prints to the works of French Impressionists and the Barbizon School. His personal struggles and psychological battles also played a significant role in shaping his art. This exploration offers a look at how these multifaceted elements intertwined to create the masterpieces we admire today.

Early Literary Influences

Van Gogh's artistic voice was shaped deeply by the literary world he grew up in. His early exposure to writers like Hugo and Zola played a significant role in how he perceived and portrayed the world through his art.

At his parents' parsonage, the family ritual of reading together became a daily practice that ingrained a deep love for literature in young Vincent. This practice wasn't just about passing time; it was a way to bond and find solace amidst life's uncertainties.

The impact of these early readings is evident in Van Gogh's art. His admiration for Victor Hugo's Les Misérables resonated deeply, as he often saw himself as the tortured Quasimodo, contending with his inner demons while finding beauty in the world around him. This identification extended into his artwork, where his expressive brushstrokes captured not just the physical world, but his emotional landscape.

Zola's novels, especially Le Ventre de Paris, had an equally powerful influence on Van Gogh's thematic choices. The book's celebration of bohemian life over bourgeois norms resonated with Van Gogh, who saw himself in the characters he read about. His compassion and humanity echoed in his personal life too, particularly in his relationship with Sien Hoornik, a prostitute he took under his wing.

Literature also shaped Van Gogh's artistic techniques. His confinement in the asylum at Saint-Rémy provided ample time for him to revisit his favorite books. The vivid descriptions of night skies in these novels inspired some of his most famous paintings, like Starry Night. His extensive reading habits helped him develop a unique narrative voice in his letters, allowing him to articulate his vision in a way that was almost poetic.

Through a blend of personal struggle and literary influence, Van Gogh crafted a new kind of art, one that was deeply intertwined with the novels and characters he cherished. His story remains a compelling narrative of human emotion and artistic genius.

Impact of Japanese Prints

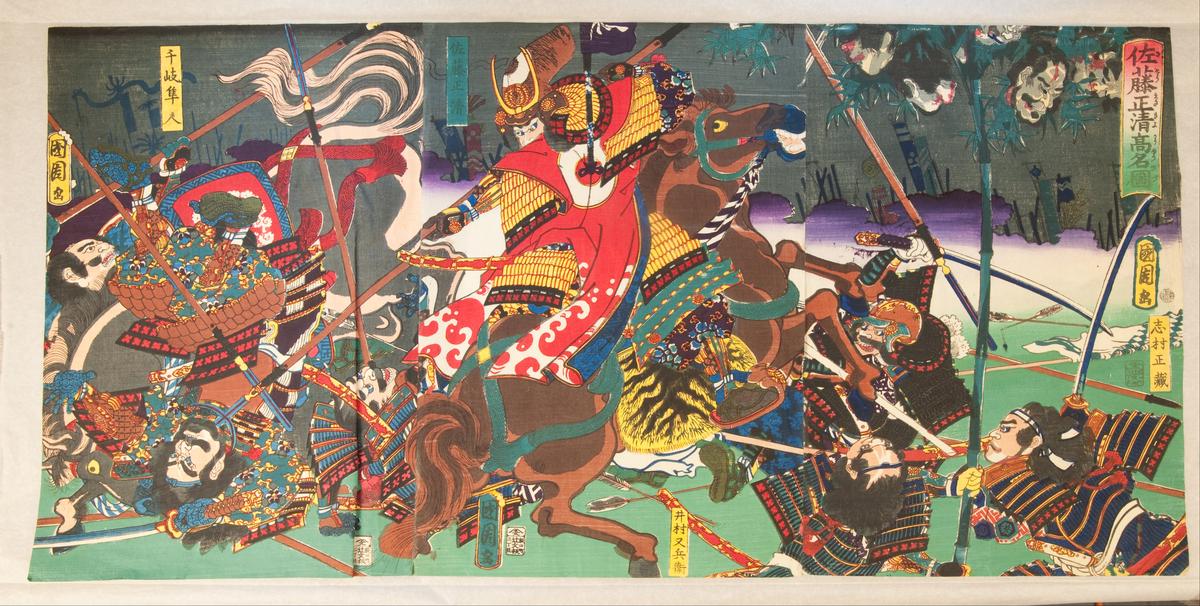

Van Gogh's fascination with Japanese ukiyo-e prints was transformative. The vibrant colors, daring compositions, and bold outlines of these prints spoke to him on a deeply instinctual level, revolutionizing his artistic direction. From the moment he was introduced to these works in Paris, he started to avidly collect them, amassing a substantial number that would go on to influence some of his most iconic pieces.

The direct impact of Japanese prints on Van Gogh's work can be seen in his approach to composition. The flat, unmodulated areas of color, and the use of bold, contour lines became a staple in Van Gogh's pieces. This shift is palpable in works like The Courtesan (after Eisen), where he pays homage to the Japanese aesthetic.

One cannot overlook how these prints redefined Van Gogh's color palette. Prior to his exposure to Japanese art, his color choices were more subdued. Post-Paris, Van Gogh embraced a bolder palette, using colors to evoke emotions rather than mirror reality. This change enabled him to express the inner vibrancy of his subjects, whether it was the sun-drenched fields of Arles or the swirling night skies above Saint-Rémy.

The thematic influence of Japanese prints was also significant. Van Gogh embraced the ethos of depicting ordinary subjects with extraordinary emotional intensity, a perspective that aligned with his own artistic ambitions. His renditions of blossoming orchards nod to the Japanese reverence for transient beauty—a concept known as mono no aware.

Moreover, Van Gogh's integration of Japanese stylistic elements allowed him to break free from the conventional rules of Western art. His almond blossoms, with their delicate, decorative branches set against tranquil backgrounds, are infused with a distinctly Eastern sensibility. Here, he blends his appreciation for natural beauty with a structured elegance that speaks volumes about his respect for Japanese craft.

Van Gogh's fervor for ukiyo-e was a profound artistic awakening. It empowered him to harmonize the visual and emotional, crafting pieces that resonated with his tumultuous spirit while celebrating the serene beauty around him. This blend of expressive passion and technical refinement became characteristic of Van Gogh's mature works, setting him apart in the annals of art history.

Influence of French Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists

Van Gogh's time in Paris marked a pivotal point in his artistic journey, fueled by his interactions with the French Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists. Upon moving to the city in 1886, Van Gogh was thrust into an environment brimming with artistic innovation and vibrancy, a stark contrast to the somber tones he had been accustomed to in the Netherlands.

The Impressionists, with their groundbreaking approach to light and color, captivated Van Gogh. Figures like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas used loose brushwork and a luminous palette that resonated deeply with the aspiring artist. This collective, with its emphasis on capturing fleeting moments and the transient effects of light, inspired Van Gogh to lighten his own palette dramatically.

Particularly influential was Camille Pissarro, whose advice and guidance helped Van Gogh refine his technique. Pissarro's blending of small brushstrokes and careful study of nature's colors found a kindred spirit in Van Gogh. This period saw a marked stylistic evolution, with Van Gogh adopting a more broken touch, capturing the essence of his subjects with a sense of immediacy and spontaneity.

Parallel to this exploration was Van Gogh's encounter with the Neo-Impressionists, particularly Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Their scientific approach to color theory fascinated Van Gogh. The technique of pointillism offered Van Gogh new possibilities in achieving vibrancy and luminosity. He began to place complementary colors side by side, not just to imitate reality but to evoke a powerful emotional response from the viewer.

The culmination of his Parisian experience was a synthesis of Impressionist spontaneity and Neo-Impressionist precision, resulting in a style that was uniquely his own. His iconic self-portraits from this time demonstrate this blend. The use of complementary colors creates a striking visual effect that captures both Van Gogh's mental state and the innovative techniques he was absorbing.

The interactions with his contemporaries also played a significant role in fostering Van Gogh's belief in the expressive power of art. Paul Gauguin, who would later join Van Gogh in Arles, shared Van Gogh's quest for a more profound, meaningful form of artistic expression. Though their collaboration was fraught with tension, the exchange of ideas between them was instrumental in pushing Van Gogh toward a more symbolic and expressive use of color and form.

Van Gogh's exposure to French Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism catalyzed a transformation that was as philosophical as it was technical. His approach to painting became more about conveying his inner world than replicating the external one. The vivacious colors and liberated brushstrokes that characterized his later works were a direct consequence of the Parisian avant-garde's influence, combined with his inherent need to inject his profound emotional and psychological experiences into his art.

Barbizon School and Millet's Influence

Van Gogh's reverence for the Barbizon School, particularly for Jean-François Millet, played a significant role in his artistic development. The Barbizon School's realistic depictions of rural life and landscapes resonated with Van Gogh's love for nature and the working class. For Van Gogh, Millet's work offered a profound reflection on the human condition, depicted through the grit and toil of peasants.

Millet's impact can be traced back to Van Gogh's early years. Millet's empathetic portrayals of peasant life provided a template for blending social realism with emotional depth. Works like The Gleaners and The Sower left a lasting impression on Van Gogh, who saw a divine dignity bestowed upon ordinary people.

Van Gogh's focus on rural themes was undoubtedly shaped by this reverence for Millet. In The Potato Eaters, Van Gogh channels Millet's influence, striving to depict the harsh realities of peasant life with unvarnished honesty. This painting is one of Van Gogh's most potent visual homages to Millet, presenting a family bound by labor and meager sustenance.

The Barbizon School's commitment to painting en plein air inspired Van Gogh to engage more directly with his environment. In Nuenen, he painted not just landscapes but also the weathered faces of peasants, finding beauty in their worn features. His numerous sketches of peasant heads reflect Millet's mission to exalt the common man.

Van Gogh also embraced Millet's technical approaches, such as his muted color palette conveying the simplicity and austerity of peasant life. Van Gogh studiously analyzed Millet's compositions, honing his ability to convey emotional depth through a limited range of colors.

Van Gogh's fascination with Millet extended beyond mimicry; it was an ideological alignment. Millet's empathetic view of the rural poor resonated with Van Gogh's desire to convey a deeper message through his art. He saw his work as a way to uplift the downtrodden and reflect their inherent worth.

Even as Van Gogh's style evolved, Millet's influence persisted. During his time in Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh created several "translations" of Millet's works, reinterpreting them with his emotional intensity and vibrant palette. These works reveal as much about Van Gogh's inner world as they do about Millet's original scenes.

In essence, Millet's influence helped Van Gogh craft a narrative through his art about human dignity and visual beauty. The Barbizon School provided Van Gogh with not just artistic techniques but a framework for understanding and depicting the profound beauty in everyday struggles, establishing him as a true heir to the Barbizon spirit.

Personal and Psychological Influences

Van Gogh's personal struggles and mental health issues are deeply intertwined with the emotional depth and psychological resonance of his artworks. Every element of his life seemed to feed directly into his creative process, making his art an authentic expression of his inner world.

Van Gogh's fraught relationship with his father is palpable in works like Still Life with Bible, where the colossal tome represents his father's rigid beliefs, juxtaposed against a French novel symbolizing Van Gogh's embrace of modernity and secularism. This painting is a visual manifestation of the ideological battles within him.

Similar inner battles echoed throughout his relationships, especially with women. His unrequited love for Kee Vos-Stricker and tumultuous relationship with Sien Hoornik, a prostitute and muse, left indelible marks on his psyche. Sorrow, a stark drawing of Sien, is a raw, poignant portrayal of despair mirroring Van Gogh's own struggles and empathetic connection to her plight.

Van Gogh's psychological state oscillated between fervent mania and debilitating depression, significantly impacting his artistic practice. The infamous episode where he severed part of his ear marked a turning point. Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear is not just a portrayal of physical injury but a profound illustration of his mental anguish.

His episodes of mental disarray didn't just hinder his artistic output; they became the crucible in which his most compelling works were forged. Starry Night, painted during his time in the Saint-Rémy asylum, is an emblematic vision encapsulating both the beauty and terror of his mental state.

Through his time in the asylum, Van Gogh continued to explore themes of isolation and contemplation. His renditions of the hospital's walled garden, such as Irises, take on a confessional tone, with the canvas becoming a therapeutic space for processing his thoughts and emotions.

Van Gogh's profound relationship with his brother Theo was a cornerstone of his psychological landscape. Their correspondence provides a window into Vincent's turbulent mind, filled with yearning, frustration, and sporadic joy. Theo was a pivotal source of emotional and financial support, reflected in paintings like The Bedroom, the embodiment of Vincent's desire for stability and comfort.

Even at the end of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise, Van Gogh's work continued to convey his inner turmoil. Wheatfield with Crows, often considered a premonition of his tragic end, radiates with foreboding and melancholy, evoking a sense of an imminent and inevitable conclusion.

Van Gogh's personal and psychological struggles were the lens through which he viewed the world and expressed himself. His art, with its rhythmic brushstrokes and emotive use of color, stands as a testament to his resilience and quest to reconcile beauty with suffering, leaving behind a legacy of profound, unguarded humanity.

Photo by gambler_94 on Unsplash