Graffiti, a highly contentious and often misunderstood art form, has engrained itself deep into the annals of human history. Steeped in societal meaning, graffiti has evolved and transmuted from primitively etched cave drawings to vibrantly adorned urban landscapes. Often representing the pulse and sentiment of societal undercurrents, it channels the voice of the unheard, breeding potent conversation within its strokes. However, it often finds itself straddling the controversial line between expression and vandalism, art and crime. This discourse delves into this fascinating world of graffiti, embarking on an informative journey through its history and influence at the intersection of art, law, and society.

Historical Overview of Graffiti

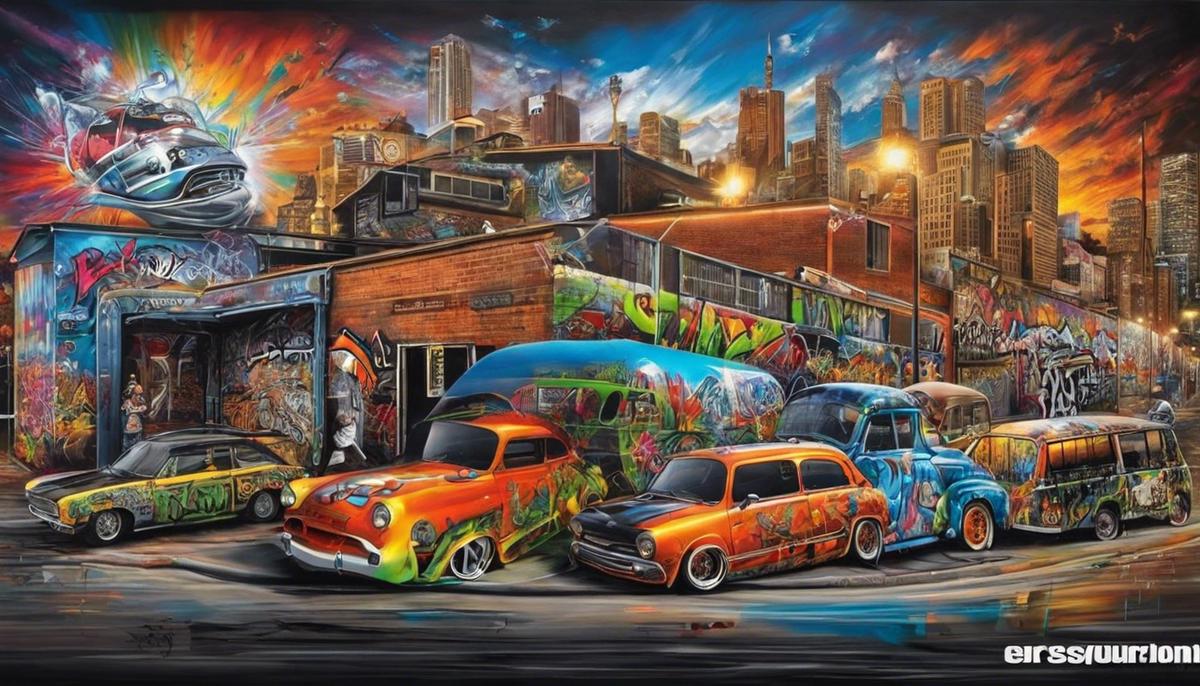

The realm of graffiti artistry, a compelling fusion of visual aesthetics and public political dialogues, has seen a drastic evolution in its perception and impact on society throughout history. Graffitists have used urban landscapes as their canvases, having unprecedented roles in reshaping the societal impressions of street art, with ancient scribbles on Roman architecture being the precursor to today’s visually striking murals.

The origins of graffiti date back to ancient civilisations. Traces of wall-etchings have been found in Egypt, Greece, and Rome, illustrating themes from everyday life to political propaganda. On the walls of Pompeii, graffiti remains were found, varied in nature ranging from electoral slogans to poetic verses. Such early forms of graffiti showcased the public’s emotions, ideas, and movements of that era.

Fast forward to the mid-20th century, graffiti saw a revolutionary metamorphosis with the advent of hip-hop culture in the United States, mainly in Philadelphia and New York City, where street walls became dynamic canvases of expression for the youth. A unique language of codes and symbols emerged, allowing individuals to make bold, anonymous statements about socio-economic and racial realities, hence earning graffiti the title of ‘voice of the youth.’ This usage of graffiti was a rebellion against the established norms, developing a new space for social critique, protest, and assertion.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, graffiti has continued to navigate the boundary between art and vandalism. On one hand, it is being celebrated in galleries and exhibitions, turning street artists into globally recognised personalities like Banksy and Jean-Michel Basquiat. On the other hand, the illegal side of graffiti, tagged on public and private properties, often results in it being denounced as vandalism that embodies societal anarchy and defacement of public spaces.

The impact graffiti has on society is thus multifaceted. As a subculture, it offers a platform to marginalised voices, fostering social dialogues and influencing political change. Yet, the law enforcement sector views it as a crime, leading to urban policies towards ‘cleaning up’ public spaces. Nonetheless, the conversation around graffiti’s legitimacy as a form of public art continues, and its influence remains profound on urban culture.

As modern-day beholders of this expressive art, we must broaden our understanding beyond the artistic surface and tap into graffiti’s historical foundations. This examination will foster an appreciation for graffiti as a medium of societal expression, bearing witness to the canvas that society itself has painted over time.

Graffiti as a Medium of Expression

Despite the understanding of the origins of graffiti and its evolution, the artistic and political essence of graffiti practices continues to pique curiosity. This multifaceted, public art form, pushing the boundaries of conventional aesthetics and political expression, is the central focus of this exploration.

On the surface, graffiti might appear as a mere spray of nonsensical symbols and signs that scrawls hastily over city walls. However, peering through the lens of an expert reveals a depth that extends beyond aesthetics. Examining graffiti through the guise of semiotics, a study of signs and symbols, unfolds its complex fabric interwoven with intricate layers of communication and expression.

In a laudable effort to define their identity and claim their ‘piece’ of the urban landscape, graffiti artists leverage the language of the streets. Their work embodies a semantic richness, with every colour, tag, and technique carrying specific implications. This improvised vocabulary, embedded within the urban culture, speaks volumes about communities and their experiences, often resonating with a socio-economic or political commentary packaged in artistic form.

Political graffiti, being a formidable tool in the hands of the socially or politically oppressed, packs the punch of a visual protest. It vindicates the rights of the silenced voices, echoing their sentiments on the canvases of urban landscapes. It was evidenced during the Arab Spring, where graffiti became the voice of the revolution, or closer home in the walls of Belfast during The Troubles. Their power lay in their simplicity and viral potential, rapidly disseminating messages and challenging the status quo.

In a world overwhelmed by digital media, graffiti retains its place as physical annotations of public spaces. The ephemeral nature of graffiti elicits a dialogue between the artist and the viewer, affirming the space as a dynamic structure of interaction. Moreover, the strategic placement of their work within the public sphere allows artists to confront their audience directly, forging an immediate connection beyond institutional art boundaries.

In recognising the transformative potential of graffiti, one must not dismiss the legal argument associated with it. While some perceive graffiti as an act of disorder and defacement, others laud it as the voice of the unheard, challenging rigid property laws. This overlap of artistry and legality stirs up a debate, catalysing dialogues on public space, urban development and social inclusion.

Navigating the world of graffiti is a fascinating journey through the arteries of urban landscapes, discovering the pulse of its identity and culture. This multi-dimensional art form reveals compelling connections between artistic practice and socio-political contexts. Therefore, graffiti functions not merely as sprayed paintings on walls, but as integral, vibrant threads weaving together stories of community identity, protest, and resistance. Just as the walls adorned with this urban ideography bear testimony to the changing sociopolitical landscape, we too can sense and appreciate the reverberations of this vibrant form of artistic expression in our everyday lives.

The Graffiti and Urban Decay Theory

On moving to more critical nuances, it appears significant to analyse the correlation between the prevalence of graffiti and perceptions of urban decay. The presence of graffiti is often seen as a key indicator of social disarray within neighbourhoods, a notion born from concept called the “Broken Window Theory.” This sociological theory suggests that visible signs of social disorder, including graffiti, contribute to a further slide into unplanned degeneration and a breeding ground for more serious offences.

However, the correlation between graffiti and urban decay is not simple or direct, as it is riddled with complexities. Firstly, it is important to acknowledge that graffiti’s social impact can be both positive and negative, depending on a myriad of contextual variables. For example, neighbourhoods with a high prevalence of stylised graffiti or murals may be viewed as culturally vibrant, contributing to aesthetic diversity and character. Areas featuring such artistic outbursts often attract tourists, foster community pride and potentially, spur on economic growth.

Various studies interlink socio-economic status to graffiti prevalence. Often, disadvantaged areas experience higher instances of graffiti. Here, graffiti can be a form of dissent, subtly marking inequality and eliciting societal change. It is these areas that most often face perceptions of disorder or decay. Consequently, graffiti becomes a scapegoat, blamed for the degradation while deeper societal issues such as poverty, inequality and political neglect remain overlooked.

Legal ramifications also play a part. Bylaws against graffiti have been implemented in some regions, contributing to the perception of graffiti as criminal activity rather than a form of artistic expression or political statement. The consequence is, graffiti becomes a symbol of lawlessness, thereby reinforcing perceptions of urban decay.

Research also unveils a counter-intuitive phenomenon- gentrification, commonly associated with urban renewal, often sparks an upsurge in graffiti. As neighbourhood demographics shift, graffiti can act as a decrying voice against socio-economic changes. Thus, even in burgeoning, upmarket neighbourhoods, graffiti can be seen as a sign of an undercurrent of discontent.

In essence, the correlation between graffiti and perceived urban decay, is vastly intricate and subjective. It is contingent upon a myriad of factors from societal attitudes, economic context to the nature of the graffiti itself. Hence, it may be reductive to set graffiti as a direct measure of urban health. While it can sometimes mirror underlying societal tension, in others it may merely be an exhibition of vibrant urban culture.

Public Perception of Graffiti: Vandalism or Art?

Public perception towards graffiti drastically influences its societal impacts, serving as an axis on which the so-called ‘graffiti discourse’ spins. For many, the devil lies in the detail; for some, graffiti is an invasive commentary on urban decay and lawlessness, while for others, it’s an avant-garde mode of creativity, personal expression and communal dialogue.

The correlation between graffiti and the perception of urban decay is intriguing. Drawing from a sociological standpoint, this can be partly traced back to the so-called “Broken Window Theory” postulated by Wilson and Kelling (1982), which advances the notion that visible signs of disorder in urban spaces, epitomised by graffiti, incite further nuisance and criminal activities. In other words, graffiti understanding is often fraught with the burden of symbolising lawlessness.

Graffiti’s prevalence in economically disadvantaged areas unveils a deeper narrative. Much more than mere scribbles on a wall, it becomes an outcry against inequality and social exclusion. The graffiti covered walls begin to reflect the discontents and frustrations of marginalised voices, and in the process, sometimes become a catalyst for social change and justice movements.

This perception of graffiti as a form of criminal activity brings with it certain legal implications. Graffiti is frequently seen as an act of vandalism with ensuing legal consequences, which continues to fuel its notoriety. However, it’s essential to contextualise these attitudes in society’s broader framework, where graffiti vandalism can arguably be seen as a form of resistance against the aesthetic hegemony of urban spaces, a claim of right to the city.

There prevails a widespread belief that graffiti indicates urban decay, but this perspective warrants scrutiny. The emergence of graffiti in certain areas often parallels gentrification processes. Sometimes, it’s the participants of this urban makeover who actively engage in graffiti artistry, causing a conspicuous increase in the occurrence of graffiti, highlighting the complexity and subjectivity of the correlation between graffiti and urban decay.

In conclusion, graffiti is a many-sided prism. Each individual lens fragment reveals a panorama of insights: From urban arguments to symbolisation of societal concerns, graffiti encapsulates a multitude complex perceptions. As vividly as the sprayers that populate the urban canvas, the differing public perceptions of graffiti helps shape its societal presence and propagate its impacts – whether as an emblem of revolution or as a sign of dereliction. The final drop of paint strikes the wall, standing testament to the enduring enigma of graffiti in contemporary society.

Legal and Social Policies Concerning Graffiti

Strategies to Manage Graffiti: Shaping Attitudes and Societal Impacts

In attempting to manage graffiti, society has adopted a myriad of strategies. Historically, these have ranged from punitive measures to proactive support. With the varying degree of effectiveness, these strategies have been integral in shaping societal attitudes and impacts of this unique form of artistic expression.

Among the most common approaches is the criminalisation of graffiti. Many cities around the world have established strict anti-graffiti laws, treating it as an act of vandalism punishable by fine or incarceration. This strategy aims to deter potential graffiti artists through fear of legal repercussions. Despite the clear intent, studies have revealed that it only has a minimal deterrent effect.

To address the concerns of graffiti as a symbol of urban decay, some municipalities have resorted to the “Clean Walls” strategy. Here, high visibility graffiti hotspots are persistently cleaned. The underlying principle is symptomatic of the “Broken Window Theory”; the belief that visible signs of crime, anti-social behaviour, and civil disorder create an environment encouraging further crime and disorder. However, many critique this approach for its ephemeral success and high maintenance cost.

Another common policy in managing graffiti is the establishment of Graffiti Free Zones. Here, designated public spaces are provided for graffiti artists to express themselves legally. While this grants a sense of legitimacy to graffiti, it is also seen as a form of containment. Additionally, its effectiveness varies greatly across different contexts. The cultural perception of graffiti and the artist’s intent are among factors that affect the success of such initiatives significantly.

Increasingly, local councils are turning to education and community-led initiatives to effect change in attitudes towards graffiti. This involves graffiti reduction workshops, mural art programs, and youth education campaigns. These initiatives are targeted at providing constructive outlets for artistic expression, and promote a healthier dialogue about graffiti in society.

Importantly, the ongoing academia-industry partnerships aim to balance graffiti’s cultural value and the societal desire for order. Well-coordinated efforts aim to transform the perception of graffiti – from unwanted public defacement to a respected form of public art – using scientific evidence and community engagement.

In conclusion, the key to managing graffiti lies not merely in implementing punitive measures, but in fostering an understanding of its cultural implications and giving credence to its artistic value. Only then can both society and artists gain mutual benefit, shaping urban aesthetics and maintaining the rich tapestry of human expression.

The discourse on graffiti remains a complex labyrinth of legal, ethical, and aesthetic dimensions. As a derivative of societal evolution, its perception is multifaceted, fluctuating between destructive criminality and a progressive form of artistic expression. Its undeniable influence on urban dynamics, socio-economic conversations, and policy making has moulded it into an inseparable, albeit controversial, element of human societal narrative. Unravelling such intricate conduits of perception, understanding, and governance, graffiti reigns as an enigmatic arena of research and dialogue. Its continued exploration is imperative to nurture a shared, evolving understanding of art, space, law, and society.