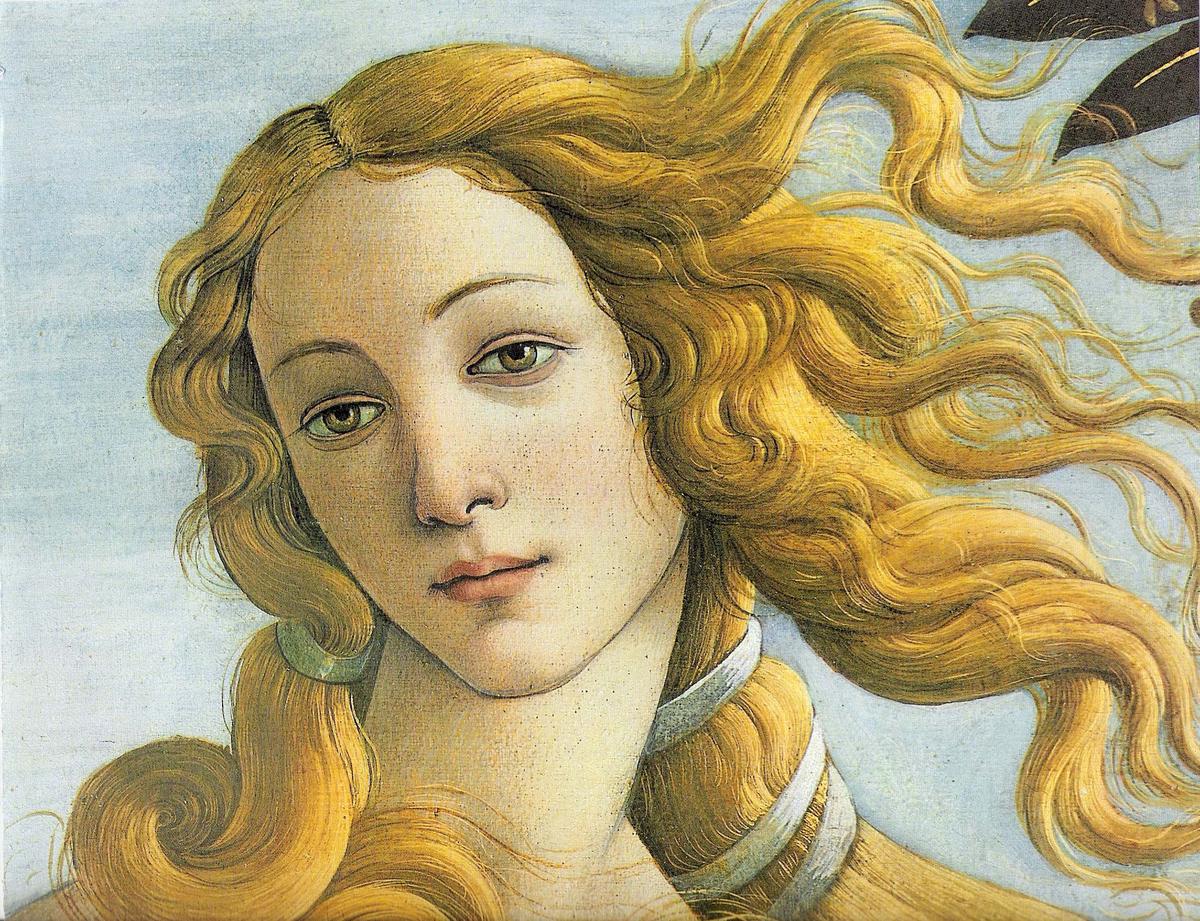

The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli's The Birth of Venus, painted during the Italian Renaissance, captivates viewers with its sublime depiction of mythological tranquility. The piece, housed at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, radiates an alluring blend of grace and mystery, exemplary of the mythological themes popular in Renaissance art.

Botticelli portrays Venus, the Roman goddess of love, at the moment of her birth, emerging from the sea and arriving at the shore, delicately poised on a scallop shell. This portrayal is rooted in classical mythology, yet Botticelli's handling brings forward a fresh vision, juxtaposing the divine with emergent human beauty.

The composition is carefully structured. Venus stands slightly off-centre, with windswept Zephyrs to her left and the welcoming figure of one of the Horae, goddesses of the seasons, draping her in a floral embroidered mantle on her right. This arrangement guides the viewer's eye across the canvas and underscores the transformation from celestial to earthly existence.

Colour plays a critical role in elucidating themes and setting the emotional tone. The use of soft pastel hues confers a dreamy quality, suggestive of an otherworldly realm. These colour choices contrast with the vibrant greens and blues representing the sea and the sky, crafting a backdrop that accentuates the paleness of Venus, highlighting her divine origin.

Botticelli's era, marked by a fervent embrace of Humanism, valued the revival and reinterpretation of classical themes through the prism of contemporary artistic explorations. The Birth of Venus mirrors this cultural revival. It recaptures ancient aesthetic ideals and elevates them through Renaissance innovations in technique and perspective, which were increasingly concerned with naturalism and the delicate rendering of human figures.

The artwork emerged at a time when Florence was pulsing with intellectual revitalization. Patrons such as the influential Medici family were enthusiastic supporters of the arts, championing works that encapsulated humanist ideals fused with classical reverence. The Birth of Venus exists as a testament to this flourishing environment; it builds a bridge between the creators of classical antiquity and the reborn artist-innovators of the Renaissance.

Under Botticelli's deft hand, the canvas becomes a delicate balance that maintains mythological profundity skewed through a humanist lens, mirroring societal shifts witnessed during his time. Each brushstroke and hue selection were aimed at drawing connotations between assigned classical narratives and their modern renditions enlightened by the epoch's philosophical pursuits.

The allure of The Birth of Venus persists, fostering dialogue and admiration as viewers reach across epochs to touch upon the same strings of wonder that vibrated under Botticelli's gaze. Such is the lasting impact of this piece that it continues to exude an aura of lyricism and beauty quintessential to both its emergence and persistent legacy within art history.

The Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo Da Vinci's The Last Supper, a mural adorning the wall of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, epitomizes the pinnacle of narrative craftsmanship, showcasing a sophisticated interplay of perspective and acute emotional narrative. Executed between 1495 and 1498, this masterpiece constitutes a seminal turning point for narrative portrayal within the context of biblical scenes.

Da Vinci's approach to perspective sets this work apart, employing a technique that extends the room within which the mural resides into the painting itself. Lines converge at the vanishing point—coincidentally, positioned at Christ's head—effecting an illusion that pulls the observer into the narrative maelstrom.

This illusion of depth affirms Da Vinci's genius in optical precision, breathing vivacity and immediacy into the scene. It effectively dramatises the critical moment—a depiction of commotion and intense human engagement in response to Christ's announcement of betrayal among His disciples. Each apostle reacts differently:

- Anger

- Disbelief

- Shock

This range underlines Da Vinci's acute understanding of human psychology; he artistically manipulates his philosophy that the motions of the mind must be rendered visible

, expertly communicated through gestures and expressions.

The Last Supper symbolizes a watershed moment for the depiction of biblical narratives, offering a concurrent unfolding of sectioning human reactions, thus shunning the hierarchical arrangement typical of religious art during prior periods. In this layout unfolds a nuanced interplay of dynamics illuminated both through celestial illumination emboldening Christ and by the characteristically stark shadowing which swathes the other participants.

The portrayal escalates the spiritual theme, deeply embedded in its sacred subject, and intricately correlates to the profound human interactions underpinning this premier event in Christian lore. Such humanization of scriptural events was a precedent in Renaissance art, precipitating endless subsequent interpretations and cascading its shadow deep into future art forms.

Leonardo's grand composition in The Last Supper seasons a pivotal impression on what came to be fundamental in Western art; a grasp of spatial depth, and more critically, its ensuing commitment to convey flawing subtextual realities capturing an unaltered emotional gravity. This masterpiece captures an ingenious rendezvous of mathematical symmetry and visual emotionality, and it stood as proof of narrative art's ultimate potential to engage humanity profoundly through the annals of time reaching beyond its immediate Renaissance cradle.

Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel Ceiling

Michelangelo's fresco on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, particularly The Creation of Adam, is a profound testament to the symphony of artistic mastery and theological symbolisation that characterised the High Renaissance. Painted between 1508 and 1512, this vast mural demonstrates exceptional artistry and embodies profound spiritual and intellectual themes central to the period.

The Creation of Adam uncovers a depiction of a biblical story and a sweeping tableau that eloquently marries divine grace with human dignity. The outstretched hands of God and Adam are near touching—an iconic representation that has become emblematic of humanity's relationship with the divine. This minute gap between the Creator's and Adam's fingers is loaded with symbolism, encapsulating the moment of life's ignition from the divine source.

Michelangelo breaks away from medieval traditions which often portrayed religious figures within stark and distant symbolisms. His portrayal of God, spirited and dynamic, contrasts sharply with older, more sedate renditions. God is depicted within a swirl of drapes, surrounded by figures likely symbolising angels or aspects of the celestial sphere, his posture animated as if moving across the heavens. This image is incredibly human, imbued with vigour, suggesting generative power and a kinetic force—the life-bringer.

Adam, on the other hand, presents a starkly different visage. His body reclines, muscles defined and detailed under Michelangelo's expert hand, illustrating the Renaissance's invigorated interest in human anatomy. His posture is both relaxed and expectant, his arm extends yet there is a palpable lassitude, perhaps hinting at the pre-life inertia soon to be vanquished by the divine spark. Michelangelo's artistic focus on human anatomy signifies the perfection of human form, an idealised vision that echoes classical antiquities and underscores Renaissance humanism's fascination with the natural man.

The space between the divine and the human in Michelangelo's fresco ponders deeper philosophical and theological questions around human existence, free will, and humanity's perpetual striving towards the divine. The exact moment captured—the instillation of life into Adam—suggests a transformative interchange bearing significant weight on interpretations of human potential and divine intention.

Technically, the work is unprecedented. Michelangelo's approach to the composition—the figures' dynamism suggested by their postures and interactions—heralded a new way of conceptualising story within art. The way light plays upon the figures' skin appears nearly tactile and suggests a depth which pulls the observer into the narrative.

In these ways, The Creation of Adam is an artistic expression and a complex theological discourse rendered in paint, a meditation on the origins of man, and a showcase of Renaissance intellect and capability. It remains a persistent echo of Renaissance ideals, resonating with modern audiences as much as it did with contemporaries.1,2 Through Michelangelo's lens, the chapel ceiling becomes a surface for religious narrative and a canvas for exploring and commenting on the very essence of human nature and its celestial counterpart.

Raphael's School of Athens

Raphael's School of Athens, housed within the Vatican's Stanza della Segnatura, epitomizes the confluence of art, philosophy, and the Renaissance vision of man. This grand fresco invites the viewer into a philosophical space populated by the great minds of antiquity, with Plato and Aristotle at its center.

The painting is more than a collection of famous figures; it is a tableau of intellectual discourse. The grand architecture, with its towering vaults and commanding pilasters, reflects the heights of human reason and inquiry. Raphael affirms and elevates the role of philosophy as the foundation for understanding the natural world.

Plato, with his upward gesture, represents the realm of ideals, while Aristotle, gesturing towards the ground, symbolizes the empirical approach to knowledge. These central figures encapsulate the dual paths of human thought offered in antiquity, presenting an enduring dialectic between idealism and realism.

Surrounding Plato and Aristotle are curious intellects engaged in robust debate and study. Raphael ties the philosophical roots of classical antiquity with the learning fervor of his contemporary world, heralding a continuum of inquiry and realization.

Raphael introduces his peers and predecessors into the conceptual forum:

- Leonardo da Vinci, characterized as the resolute Heraclitus, adopts solitude, underlining his unique philosophical isolation.

- Michelangelo, earnest and retracted, dons the aspect of Heraclitus, a nod to his brooding intellect and stately defiance.

The School of Athens asserts itself as a vivacious endorsement of humanist ideals, where knowledge uplifts the participants to more than their earthly bearings. Its influence seeps into how intellect and its figures are consistently portrayed henceforth – enlightened, engaged, and poised in dynamic discourse.

The painting espouses an intellectual ideal and serves as an institutional memory of who asks the questions and how they were debated. Raphael avows that the pursuit of knowledge and its rich history forms discourse and substantial human progress. This fresco's philosophical gallery, freezing thinkers in perpetual intellectual motion, spawns legions of imitators and evolves into a foundational art piece directing future portrayals of intellectual engagement.

The School of Athens echoes across art and time, offering a lesson in discourse and study. It reflects the Renaissance spirit, where reason and knowledge are exalted, and intellectual enrichment is celebrated as a testament to human progress.

Primavera by Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli's Primavera, housed in Florence's Uffizi Gallery, stands as another monumental testament to the Renaissance's engagement with Classical myth and its confluence with Humanist philosophy. This tempera on panel transcends its immediate visual allure by encoding a layered allegorical narrative ripe with Neoplatonic insights.

The essence of Primavera revolves around an allegorical representation of the rejuvenation associated with spring. However, it serves as an embodiment of Renaissance Neoplatonic ideals, seeking to synthesize material sensuality with spiritual pursuits.

Central to the artwork is Venus, surrounded by mythological figures including:

- Mercury

- The Three Graces

- Zephyrus pursuing the nymph Chloris who metamorphoses into Flora

Botticelli's layout enacts a sublime allegorical tableau, inviting interpretations through the lens of human transformation and metaphysical ascendancy. This sequence symbolically marries the material physicality with the spiritual and philosophical renewal.

Above Venus, Cupid draws his bow, gesturing towards love as a universal and indiscriminate force, heightening the concept of divine love aligned with intellectual ascendance. Venus herself stands calm, symbolically emphasizing her role as love's moderator aligned with intellectual beauty and order.

The depicted Orange Groves can be contemplated as the Gardens of the Hesperides, introducing hints to immortality, weaving classical mythology into the art.1

Botticelli crafts each figure and pose to draw upon numerous levels of allegorical representation, demonstrating his attempted codification of Neoplatonic philosophy, which saw physical beauty as a tangible conduit to perceive spiritual beauty.

Through Primavera, Botticelli extols not merely Spring but weaves an intricate ideological fervor reflective of his time's intellectual currents. He provides a contemplative space wherein the visages of myth serve as both narrative entities and emblematic bearers of the Renaissance's ideological accolades and trials.

Primavera emerges as a paragon of how art during the Renaissance was pressed into service as both an aesthetic and philosophical arsenal, contributing vividly to a period infatuated yet critically engaged with reflecting on Classical antiquity.

The enduring allure of Renaissance art lies not merely in its visual magnificence but in its capacity to engage with profound philosophical and theological themes. Through a detailed examination of these masterpieces, we gain a richer understanding of how art served as a medium for intellectual and spiritual inquiry during the Renaissance, reflecting a profound dialogue between the human and the divine.