(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1890

Died: 1973

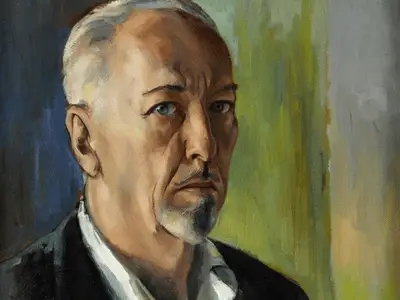

Summary of Stanton Macdonald-Wright

St. Stanton MacDonald-Wright, a pioneer of modern art in Los Angeles and one of the first American avant-garde artists to receive international attention, is best known for his work with Synchromism. Artworks of all kinds, both abstract and more traditional figurative, were influenced by his belief in the power of colour and his study of Asian art and culture.

With Morgan Russell, Stanton Macdonald-Wright developed the first American modernist style of painting, which was influenced by European modernism. As a pioneer of non-objective painting, he has embraced abstraction and relied on colour and form to convey meaning. His Synchromist works were among the first abstract paintings of the 20th century, even though he would return to figuration later in his career.

Macdonald-Wright experimented with the notion of synesthesia, a popular artistic and scientific concept at the time that also featured in the work of French Symbolists, the Orphists like Robert Delaunay, and the German Expressionist Wassily Kandinsky. Macdonald-Wright was instrumental in the development of abstract art in Paris during the 1910s, and he passed these ideas on to his American colleagues.

First modern art exhibition in LA organised by Macdonald-Wright and a community of modern artists on the West Coast were a result of his efforts. Young Californian artists were inspired by his teachings and writings on colour theory, providing an alternative to New York City as a cultural centre. During the 1930s, he worked for the Works Progress Administration in California, where he provided training and opportunities for a large number of people.

He was a critical advocate for the relevance of early American modernist painting during the peak of Abstract Expressionism, when Macdonald-Neo-Synchromist Wright’s style was developed. Color theory in particular was an important part of American Modernism that was overlooked until he brought it to light.

Childhood

After his mother’s admiration for Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Stanton MacDonald-first Wright’s name was given to him by his father, Archibald Davenport Wright. His father owned a beachfront hotel in Santa Monica, where the family lived comfortably. Stanton was encouraged by Archibald Wright, an amateur artist, who enrolled him in private art lessons when he was a child. Willard Huntington Wright, Wright’s older brother, was an art critic and art writer who later wrote the popular Philo Vance detective novels under the pseudonym S.S. Van Dine.

The boys were sent to a local Catholic school, despite the fact that their parents were not Catholic. Stanton is said to have been the go-to guy for the nuns whenever they needed help with a creative project. The Art Students League in Los Angeles, where Warren T. Hedges, a former student of Robert Henri’s, taught Stanton how to draw and paint when he was thirteen years old. Stanton was introduced to the Ashcan School style and the importance of incorporating one’s own thoughts and feelings into one’s artwork as a result of this. In the early stages of his career, he was influenced by California Impressionism.

Early Life

After only two weeks of getting to know one another as guests at his father’s hotel, seventeen-year-old Macdonald-Wright married Ida Wyman in 1907. Upon moving to Paris, the young couple attended the Sorbonne, the Académie Julian, the École des Beaux-Arts, and the Académie Colarossi. Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, Gertrude and Leo Stein, and fellow American student Thomas Hart Benton were among those Stanton met while in Paris. On his way to becoming an optical scientist, Michel-Eugène Chevreul and Hermann von Helmholtz piqued his interest in colour theory. In particular, Macdonald-Wright would be influenced by Chevreul’s writing on “simultaneous contrast,” which studies how colours interact with one another.

Morgan Russell, a fellow American student in Paris, struck up a friendship with Macdonald-Wright. Percyval Tudor-Hart, a Canadian painter and colour theory advocate, taught the two friends from 1911 to 1913. They learned to associate colour with music from Tudor-Hart (in fact, he directly correlated the twelve colours of the spectrum with the twelve steps of the musical scale, and used this scheme to compose visual “melodies”). Harmonious visual compositions could be created by selecting “colour chords” derived from chromatic scales in which each colour was assigned a note on the musical scale, painters claimed. Saturation and hue were used to convey pitch, while luminosity was used to convey tone.

Color was used in an abstract, rather than representational, manner in the Synchromism style developed by Macdonald-Wright and Russell. Analogous to musical composition, they combined planned intervals and chords with more improvisational ones. Their paintings, they reasoned, could elicit feelings and sensations by emphasising the materiality and tactility of colour through the use of juxtaposed planes of colour. MacDonald-Wright explained that “Synchromism simply means ‘with colour’ as symphony means symphony with sound,'” and that was the driving force behind the movement. The first Synchronist exhibition was held in Munich in June 1913.

According to MacDonald-Wright and Russell, “Yellow-Orange has also a braggart tendency, but at bottom it is weak and sickly…. It’s as if the pompous soul’s last pretences have been extinguished. According to this account “it’s almost sad, like an old man who feels senility is just around the corner,” Synchromists aimed to emphasise colour as both subject and theme, but some of their works were less abstract. As compared to Russell’s works, MacDonald-Wright experimented with more figurative subjects (often the ideal male form), but in an abstracted and nearly cubist faceted manner.

In the development of Synchromism, the Romanticist painter Eugène Delacroix’s writing on colour, particularly his work with complementary colours, was crucial. Additionally, MacDonald-Wright was influenced by Paul Cézanne, who he believed had used colour in a more structural (rather than decorative) manner. After experimenting with the Post-Impressionist style of Cézanne, he owned four of his watercolours. Landscapes by JMW Turner, he said, “removed all the gross materialism out of objects and has given me the essence of the beautiful.” which he credited to Turner.

Synchromism incorporated elements of Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism, and German Expressionism by relying on colour alone. Indeed, abstract art of the early 20th century frequently explored the connections between colour, music, and sensation. Despite the fact that Synchromism was one of the earliest to emerge, other abstract artists were quick to dismiss it as merely borrowing from Orphism or Cubism. Although their grandiose language may have contributed to the critics’ hostility, Macdonald-Wright adamantly denied these influences. Aiming to distinguish Synchromism from other similar movements, Macdonald-Wright and Russell wrote in exhibition catalogues about their preference for gradations of colour in order to express “the depth of space,” as well as calling Futurism “superficial.” They also found Orphism to be light, flimsy, and merely decorative.

He and his brother Willard Huntington Wright moved to London at the beginning of World War I, where they stayed for the next two years. They collaborated on three art books that were later published in New York during this period. The most well-known, Modern Painting: Its Tendency and Meaning (1915), provided an overview of major modernist art movements that foretold the rise of abstraction over realism in the near future (simultaneously championing Synchromism). When Macdonald-Wright returned to painting figurative elements during these years, he often drew inspiration from the Greco-Roman tradition. Many artists turned to the classical past during World War II as a means of escaping the current turmoil and as a historical link that went beyond the current political climate.

He moved to New York City in 1915, where he lived with Thomas Hart Benton and made a bid for American recognition. Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery hosted his first solo show in 1917, and he participated in the Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters (organised by his brother) the year before. In spite of this minor success, he was unable to achieve the level of fame and financial stability he had hoped for. Ending up in New York, he taught painting lessons and created posters and illustrations (often under the pseudonym “d’Este.”) to earn money. However, in 1916, Morgan Russell decided to abandon the Synchromist approach.

Mid Life

For the first time in his career, Macdonald-Wright left New York for Los Angeles to see if he could succeed there. With the help of Alfred Stieglitz, he organised “The Exhibition of American Modernists,” the first modern art show in Los Angeles. The exhibition was held at the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art and featured works by John Marin, Arthur Dove, and Marsden Hartley, among others. Attendance and press coverage were favourable, but sales were disappointing.

“sterile artistic formulism” of modern art soon after this exhibition, Macdonald-Wright decided, and even found Synchromism to be stale and academic. From 1921 onward, he stopped using the style (to revisit it in 1953). The Los Angeles Art Students League, where he was director from 1922 to 1930, adopted his “intelligent drawing.” curriculum and encouraged students to work with live models rather than traditional plaster casts. Only 60 copies of his textbook Treatise on Color were made available in 1924, with the bulk of the copies going to his students. As a result of this book’s widespread circulation and reproductions, color-based abstract painting would be transformed.

Following his studies of the East in Paris during 1912, he continued to expand those studies in the 1920s. As a director, designer of sets, and actor for the Santa Monica Theater Guild, he wrote four plays with a Chinese theme while also studying art, philosophy, and literature at UCLA. “Western philosophy has tried to solve the universal mystery by means of finding an absolute rather than accepting, as the Chinese have, the mystery as fait accompli.” he wrote in his esoteric paintings.

Macdonald-Wright was chosen to paint a series of murals for the Santa Monica Library as part of the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), a pilot for the larger Works Progress Administration (WPA), which employed artists during the Great Depression. As Macdonald-18-month Wright’s project depicting the evolution of mankind was completed, he used his own salary to pay other struggling artists. Beginning in 1935, he also served as WPA Director for Southern California and WPA Technical Advisor for seven Western states as part of his duties. WPA artists were under his direct supervision for seven years, and he was personally responsible for completing a number of important projects.

After serving as a professor of art history and oriental aesthetics at universities across the United States for more than two decades, Macdonald-Wright retired from teaching in 1952. The Fulbright exchange professor went to Japan for two years in 1952 and 1953, where he taught at Kyoiku Daigaku (the Tokyo University of Education).

Late Life

His “neo-synchromist” work was produced in 1954, when Macdonald-Wright retired from teaching and returned to abstract painting. Using elements of Eastern art and principles of Synchomism in these works, he experimented further. After reflecting on this artistic awakening, MacDonald-Wright stated that it had a profound effect on him “At first, I was astonished by my new painting because I had made the ‘great circle,’ returning 35 years later to a style of painting that looked a lot like my youth. However, at the core, I had achieved an interior realism, or yugen, as it is known in Japanese. The quality of hidden reality was what I felt I was lacking in my younger years, and this sense of reality cannot be seen but is evident by feeling.” Neo-Synchromist paintings by MacDonald-Wright were praised by the renowned Alfred Barr Jr., an American art historian and the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, for having a stronger sense of luminosity and “a deeper spirituality.”

At Kenninji Zen monastery, in central Kyoto, in 1958, Macdonald-Wright spent five months a year learning about Japanese art and poetry, and painting extensively. His Synchome Kineidoscope was completed the following year, in 1959, by MacDonald-Wright after decades of planning. The building’s goal was to “make a painting exist and change through a period of time.” Color, light, sound, movement, and time were all part of his original vision for this piece, which he envisioned as a synthesis of artistic media.

Color painting by Macdonald-Wright has seen a resurgence of interest in recent years. The Smithsonian National Collection of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C., the Art Galleries of UCLA, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art all hosted retrospectives of his work. “Synchromism and American Color Abstraction: 1910-1925” was organised by the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1978-1979, a six-museum travelling exhibition of earlier Synchromist works.

At the age of eighty-three, Stanton Macdonald-Wright died at his home in Pacific Palisades, California.

Modernist abstraction was introduced to the United States through Synchromism, despite it not being a commercial success in the 1910s. Color theory and musicality from Europe also influenced avant-garde artists in New York and Los Angeles, who were influenced by the European influence. Macdonald-Wright paintings were described as “Theory plus feeling – They are really great.” by Georgia O’Keeffe in 1916. “the greatest master of colour in painting that ever lived.” was Robert Henri’s assessment of Macdonald-Wright.

Influenced by Macdonald-Wright, American abstraction developed significantly. Jules Olitski, Stuart Davis, and Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Dasburg were among the artists who experimented with Synchromism and aimed to connect colour and music. Synchromist ideas can also be found in the works of Joseph Stella, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Alfred Maurer, and Georgia O’Keeffe, according to curator Marilyn Kushner.

As a result of his teaching and administrative roles, Macdonald-Wright had a significant impact. Treatise on Color (1924), in particular, may have had an impact on abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock, who were influenced by his teaching. A generation of artists were able to earn money through Macdonald-WPA Wright’s work, but he advocated for the programme to support styles other than American Regionalism.

Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting were directly linked to the early stages of twentieth-century American abstraction by Macdonald-Neo-synchromist Wright’s paintings from the post-World War II era. He played a pivotal role in bridging the gap between abstract art of the 1950s and 1960s and the work of earlier painters.

In addition, Macdonald-Wright organised a number of exhibitions outside of New York, including the first Modern Art exhibition ever held in Los Angeles, which brought abstract art to the public’s attention. Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight says it’s impossible to understand 20th-century art in LA without understanding Macdonald-work Wright’s and career.

Famous Art by Stanton Macdonald-Wright

Synchromy #3

1915-1916

To create a three-dimensional rhythm across the two-dimensional canvas, this painting employs colour in an abstracted fashion, allowing it to serve as both the subject and theme. “bumps and hollows,” were described by Macdonald-Wright as bringing the painting’s flat surface closer to a sculpture.

Au Café (Synchromy)

1918

For Macdonald-Wright, the shift from pure abstract synchromies to figurative images is evident in this piece. The shimmering facets of colour allow the viewer to piece together a pair of figures: a seated man in the lower right corner faces a woman in a hat who is raising a wine glass to her lips. Macdonald-mature Wright’s paintings, after an initial phase of abstraction, would include a certain amount of representational figuration along with his colour theory in order to create suggestive atmospheres and layered meanings.

Oriental Synchromy in Blue-Green

1918

The canvas is filled with geometric planes of colour (mainly blues and greens, but also orange and yellow) that give the impression of an abstract composition at first glance. Amidst these planes, four human figures are clearly visible but obscured to the point where one figure ends and another begins. Fragmentary figural elements, such as a face, bent elbow, and raised arm, can still be discerned by the observer in this painting. These pulsating colour fields have a human element to them.

Synchromy in Purple

1918-1919

With this in mind, Macdonald-Wright incorporated objects into Synchromism in works like this to avoid “aimless free decoration,” As a result of this evolution, Macdonald-Wright was able to more directly link his painting to the Old Masters, creating an artistic legacy for the movement. Both Macdonald-Wright and Russell were heavily influenced by Michelangelo’s sculptures, and both sought to reimagine strong, muscular men in their own works. In a 1964 interview, Macdonald-Wright said of Michelangelo, “He was a genius.” “One of the most talented illustrators I’ve ever seen, if not the best. He was the end of sculpture for me. It’s been over a century since Michelangelo’s masterpieces.”

History of Santa Monica and the Bay District

1941

With the help of the Synchromist principle of harmonious colours, MacDonald-Wright brought an otherwise conventionally rendered figurative image into the 21st century. A more realistic style was chosen to appeal to the public who would be using the city hall of Santa Monica as a backdrop for this mural, like many WPA murals. Two Native Americans kneeling in prayer, two Spanish conquistadors, and a Franciscan priest are depicted in the painting. On the feast day of St. Monica, Father Juan Crespi, a member of the 1769 Portola expedition, recounts a meeting between the expedition members and Native Americans (August 27). Father Crespi remarked that the spring raindrops reminded him of Saint Monica’s tears. As a gesture of warmth, welcoming, and kindness, the Native Americans escorted the Spanish to a freshwater spring.

An Old Pond, a Frog Leaps in the Sound of Water

1966-1967

Macdonald-“Haiga,” Wright’s a collection of twenty woodblock prints intended to accompany famous Japanese haikus, is the source of this piece. The image shows his intent to combine Asian culture and traditional techniques with the principles of Synchromy. To deepen his knowledge of Japanese art, poetry, and culture, Macdonald-Wright began annual residencies at the Kenninji monastery in Kyoto beginning in 1958, where he stayed for two years.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- St. Stanton MacDonald-Wright, a pioneer of modern art in Los Angeles and one of the first American avant-garde artists to receive international attention, is best known for his work with Synchromism.

- He and his brother Willard Huntington Wright moved to London at the beginning of World War I, where they stayed for the next two years.

- With the help of Alfred Stieglitz, he organised “The Exhibition of American Modernists,” the first modern art show in Los Angeles.

- After serving as a professor of art history and oriental aesthetics at universities across the United States for more than two decades, Macdonald-Wright retired from teaching in 1952.

- Modernist abstraction was introduced to the United States through Synchromism, despite it not being a commercial success in the 1910s.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.