From the earliest etchings on cave walls to the vibrant splash of digital pixels, the journey of storytelling through sequential art has been a testament to human creativity and the relentless pursuit of communication. This narrative traces the evolution of graphic storytelling, shedding light on how each leap forward in technique and technology has contributed to the rich tapestry of visual narratives we cherish today.

The Genesis of Graphic Storytelling

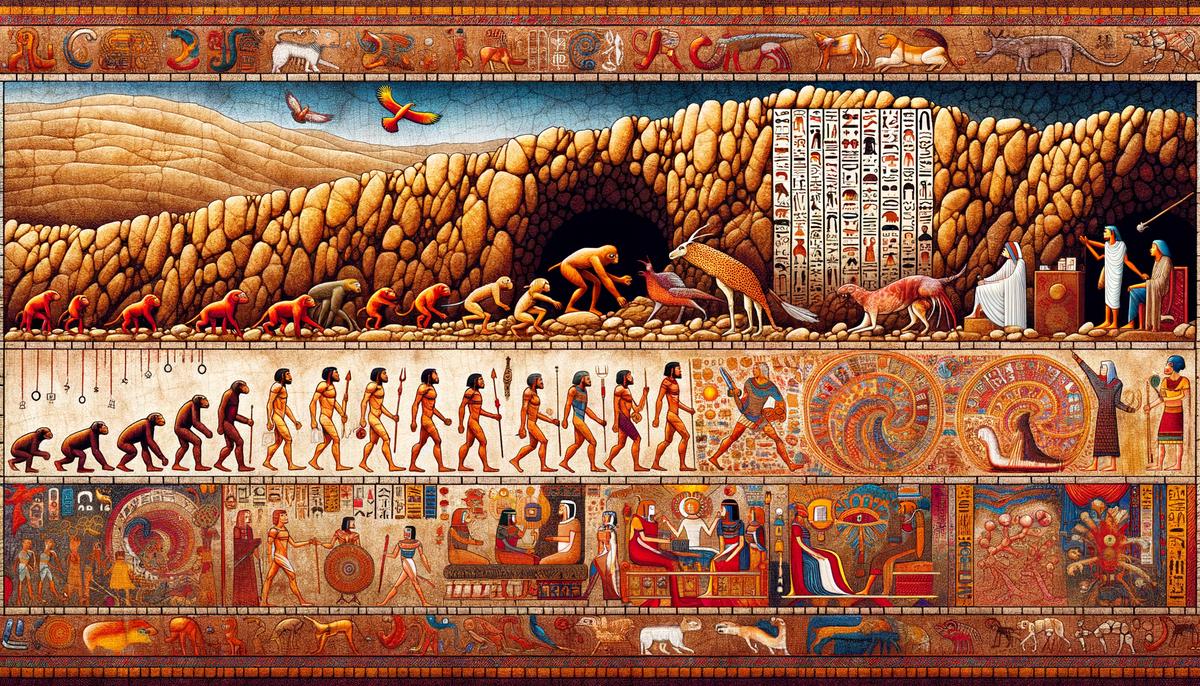

Ancient cave paintings were among the first attempts by humans to capture stories and convey messages using visuals. These early artworks, found in places like Lascaux, France, depict animals and hunting scenes, showing a chronological sequence that can be seen as a precursor to storytelling through sequential art.

Egyptian hieroglyphs took this concept further by combining pictorial images with symbols and words to communicate more complex narratives. These carvings, which adorned the walls of tombs and temples, narrated the lives of gods and pharaohs, providing a direct lineage to the narrative techniques used in modern comics and graphic novels.

- In medieval Europe, tapestries such as the Bayeux Tapestry served a similar narrative function. This embroidered cloth, over 230 feet long, depicts the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England in 1066. Its sequential nature, with scenes flowing into each other much like the panels of a comic strip, demonstrates an evolving understanding of visual storytelling.

- The invention of the printing press in the 15th century by Johannes Gutenberg was a pivotal moment for sequential art. It enabled the mass production of images and texts, leading to the proliferation of illustrated books and broadsheets that used sequential images to tell stories or depict satirical scenes, making them accessible to a broader audience.

Political cartoons of the 17th and 18th centuries further pushed the possibilities of visual narrative. Artists like William Hogarth created prints such as “A Harlot’s Progress,” which told moral stories through a series of images intended to be viewed in sequence. This method closely resembles the episodic nature of many modern graphic novels. In the 19th century, Rodolphe Töpffer, a Swiss artist and writer, is often credited with creating the first true comic strips. His works combined sequential images and text captions in a manner that directly influenced the structure of contemporary comics, formalizing a method for delivering narratives visually. The advent of technology and the rise of popular newspapers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the birth of the comic strip as we know it today. Cartoonists like Richard F. Outcault introduced characters like “The Yellow Kid,” employing speech balloons for dialogue and serialized storylines that captivated readers, embodying the essence of both traditional comic strips and the later graphic novels.

In summary, the evolution from ancient cave paintings through to Egyptian hieroglyphs, medieval tapestries, and the influence of the printing press demonstrates a steady progression towards more sophisticated forms of sequential art. Each advance brought a deeper understanding of how images can be used to tell stories, culminating in the richly diverse world of comics and graphic novels that we enjoy today. This lineage not only highlights humanity’s enduring desire to tell stories visually but also showcases the adaptability and innovation inherent in the art form.

The Golden Age of Comics

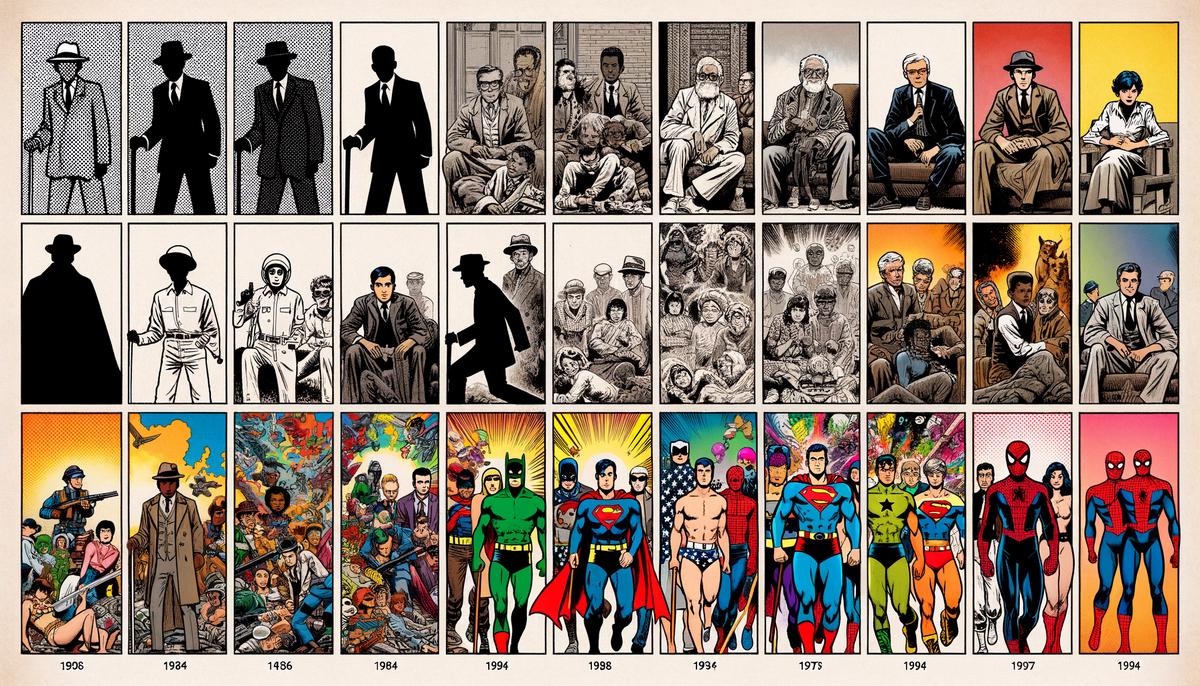

Entering the late 1930s, a fresh breeze hit the storytelling landscape, ushering in the Golden Age of Comics, significantly marked by the appearance of superhero tales that soon captured the hearts and minds of American readers. This era not only gifted readers with a plethora of iconic characters like Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman but also offered a rich tapestry that interwove the fantastical with the real, providing solace and inspiration during the challenging periods of the Great Depression and World War II.

The seeds for this transformative period were planted when Superman soared into the scene in 1938, courtesy of Action Comics #1. This groundbreaking moment wasn’t just about introducing a character; it was the dawn of the superhero genre as we know it. Superman’s otherworldly powers and morally upright persona set the template for countless heroes to follow, embodying a form of escapism that was desperately needed in a country grappling with economic hardship and the looming specter of global conflict.

What followed was a creative explosion, with publishers racing to capitalize on this newfound appetite for superhero stories. Batman entered the fray not long after, offering readers a grittier, more brooding hero, whose night-time crusades against Gotham’s underworld provided a dark counterpoint to Superman’s sunny optimism. Meanwhile, Wonder Woman’s debut in 1941 brought an icon of female strength and independence to a world where women were beginning to take on new roles in society and the workforce due to the war effort.

This surge in popularity was bolstered by technological advances in printing and distribution. Improved color processing and faster presses meant that comics could be produced more quickly, with more vibrant artwork that leapt off the page. The developments in the distribution network allowed these colorful tales to spread across the nation like wildfire, finding eager audiences in every corner of the country. A weekly trip to the comic book stand became a hallowed ritual for many, providing a regular intake of adventure and excitement.

Comic books during this golden period did more than just tell fanciful tales of caped crusaders; they mirrored and influenced American society. Characters regularly confronted axis powers, bolstering home-front morale. Comics served not only as escapism but as a subtle form of propaganda, rallying readers around the war effort and presenting the conflicts overseas in black and white terms of good versus evil.

The genre’s impact extended beyond wartime, igniting debates on morality, justice, and the American way of life. Superman’s “truth, justice, and the American way” wasn’t just a catchy slogan; it encapsulated the era’s ideals and aspirations. In the pages of these early comic books, readers found not only entertainment but also a source of inspiration, a guide for navigating the challenges of their times.

As the Golden Age comics streaked across the skies of American culture, they left an indelible mark on the national psyche and laid the foundational myths for generations to come. These stories and characters became a vital part of America’s cultural fabric, enduring in popularity and influence long after the war had ended and peace had returned. The era showcased the boundless possibilities of the comic book medium, transforming it from humble beginnings into a powerful tool for storytelling and leaving a legacy that modern comics continue to build upon.

The Graphic Novel Revolution

As the vibrant hues of Golden Age comics settled into a staple of American culture, a shift heralded the transition from ephemeral pop culture to enduring artistry. Enter graphic novels—the decade-straddling progression transformed comics from a subculture into mainline recognition. This renaissance pivoted around groundbreaking works such as ‘Maus’ by Art Spiegelman and ‘Watchmen’ by Alan Moore, which transcended typical expectations. ‘Maus,’ with its poignant recounting of Holocaust survival using animals to depict humans, shattered the illusion that comics could only serve as light entertainment. Each frame meticulously woven with historical gravitas, Spiegelman elevated the comic form to a compelling autobiographical narrative, unearthing the deep emotional and psychological layers often reserved for traditional literature.

Similarly, ‘Watchmen’ embarked on a deconstruction of the superhero archetype, complicating the landscape with moral ambiguity, political commentary, and existential musings on power and identity. This wasn’t just a story about capes and villains; it was a reflection on the concept of heroism itself, wrapped in a complex narrative structure only achievable through the unique marriage of word and image inherent to comics. The dark, multi-layered story served as a commentary on the times, pulling the superhero from his pedestal to ask: What does it mean to be a hero in a flawed world?

This period saw graphic novels stepping boldly into the sphere of serious literary critique, fetching awards normally reserved for ‘higher’ forms of art and literature. Libraries began to shelf them alongside classic novels, and academia opened their doors to studying graphic novels as a form of narrative worth examining.

Their visual nature, once a barrier for adult engagement, bridged generational gaps. Readers found themselves entranced by the depth of storytelling achievable when images and text combined. It challenged the preconceived notion that visual narratives were solely for children or the uneducated, inviting a broader audience to experience stories in a novel way.

Through these seminal works, graphic novels carved a niche within the literary world that proved comics could not only match but sometimes exceed the narrative complexity and thematic depth of traditional texts. The impact was revolutionary, heralding a newfound respect and interest in visual storytelling’s potential.

Instead of replacing traditional comics, graphic novels complemented and expanded the form’s horizons. The non-linear narratives and thematic complexities allowed for new stories to be told, stories that reflected the changing, more mature audience’s interests and concerns.

This emergence represented more than a mere shift in public perception; it was a reclaiming of comic’s rightful place in the annals of meaningful storytelling. With each panel and page turn, graphic novels underscore veritable truths—emotions charted in ink, identities scripted within balloons, and social commentary penciled across panels—all culminating in a medium that resonates deeply with its beholders.

In turn, artists and writers were emboldened to push boundaries further, harnessing this form to explore and critique life’s intricacies with an honesty and creativity impossible to ignore. The rise of graphic novels unveiled the comic medium’s capability for profound storytelling, moving beyond simplicity to embrace sophistication, artistry, and relevance that endures well into the current century.

Censorship Battles and the Comics Code Authority

In the shadow of a vibrant era for comics, the outbreak of moral panic in the 1950s anchored a period of tumultuous challenge and censorship. Central to this storm was the publication of Fredric Wertham’s “Seduction of the Innocent,” which pointed fingers at comic books, accusing them of corrupting the youth with images and narratives of violence, crime, and immorality. This accusation stoked fears across America, spiraling into a national dilemma over the content children were consuming.

The Comics Code Authority (CCA) emerged as a knee-jerk response, a self-regulatory body devised by publishers to pacify public outcry. With guidelines that were Kafkaesque in their limitations, the CCA stamped out not just explicit content but any form of storytelling that dared to challenge the status quo. Vampires, werewolves, and zombies vanished overnight, along with portrayals of dissent, subversion, or any complexity of moral ambiguity. Love stories, crime narratives, even superhero tales—all were sanitized to meet the stringent new standards that governed everything from the style of artwork to plot resolutions that invariably rewarded virtue and punished wickedness.

Nevertheless, this age of censorship inadvertently spurred an era of creativity under constraint. Writers and artists found inventive ways to weave meaningful stories within the tight boundaries of the Code. Symbols and subtext became tools more powerful than open defiance. Superheroes evolved from mere adventurers fighting external foes to more complex characters struggling with internal dilemmas, echoing the larger societal shifts of post-war America.

The decline of the CCA’s grip began slowly, catalyzed by the underground comix movement and figures like Robert Crumb who ignored the CCA entirely. These creators, together with independent publishers, birthed narratives bursting at the seams with political satire, cultural critique, and explorations of identity and sexuality—themes scarcely imagined under the Code’s restrictions.

As mainstream publishers noticed the shifting tides and groundbreaking works like “Maus” and “Watchmen” made waves beyond the comics’ customary circles, the need for the Comics Code faded into an anachronism. Marvel Comics broke ranks in the early 1970s, publishing issues of “The Amazing Spider-Man” that addressed drug abuse, explicitly flouting CCA regulations to do so. By presenting real-world issues, comics reconnected with their roots as a mirror to society, fostering empathy and understanding through their panels.

DC Comics’ eventual abandonment of the CCA in favor of their rating system further cemented this shift, signaling an era where creators could again explore the multifaceted human experience without censorship’s harsh shadow. This evolution reflected a society inching ever closer to embracing diversity and complexity in storytelling and acknowledging comics as a mature art form capable of grappling with weighty themes.

In navigating through and beyond censorship, comics and graphic novels matured, pushing past the boundaries of mere escapism to probe questions of morality, identity, and society. By embracing this complexity, creators have ensured the medium’s enduring relevance, carving a space where images and words come together to challenge, reflect, and explore the depths of human experience.

The Digital Age and Beyond

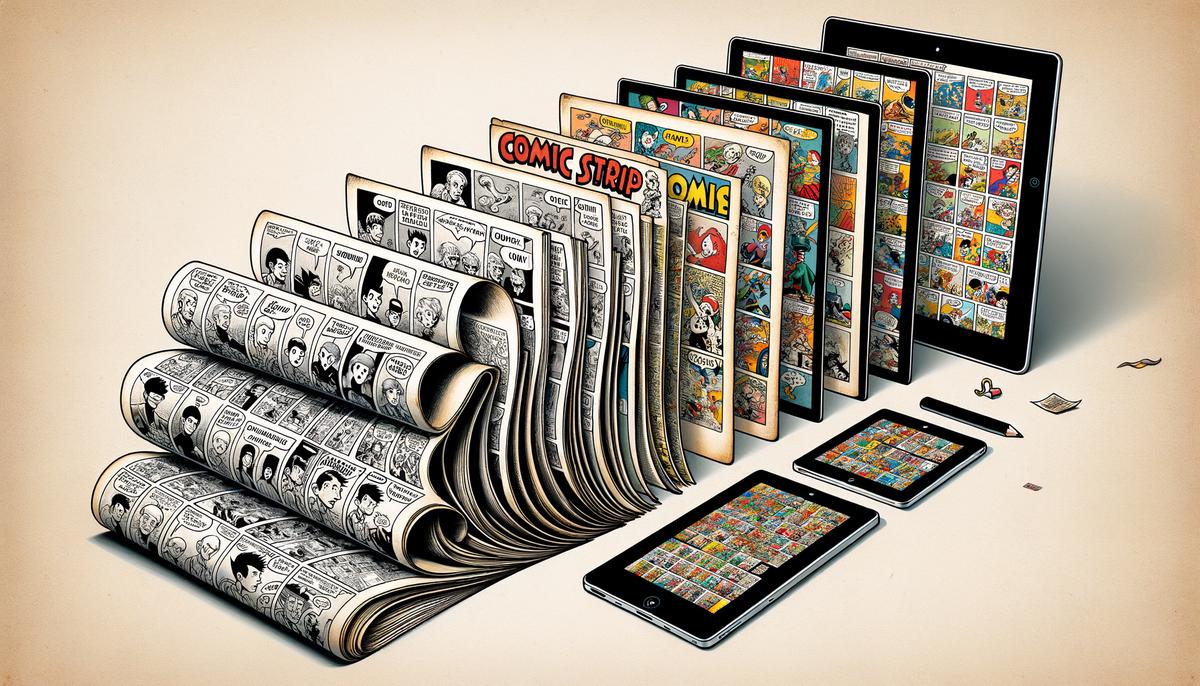

As we vault over the digital divide, comics and graphic novels carve out new territories that blend ancient tradition with blinking-beacon technology. The rise of webcomics flips the script, offering storytellers worldwide a digital stage. These pixel panels blur the line between professional and amateur, changing how we define the creator and audience. High barriers to entry, once guarded by gatekeepers of publishing, now crumble under the weight of the internet’s democratization. Anyone with a story can find a niche.

Digital distribution platforms, from ComiXology to WEBTOON, have turbocharged access to this sequential art. Readers no longer trudge to specialized shops but have global libraries in their pockets. This convenience expands audiences, pulling in those who might never have leafed through a comic book otherwise. Yet, this bounty comes with its own beasts. Discoverability in a sea of content poses a significant hurdle, despite algorithms’ promise to guide us to our next favorite read.

The digital era democratizes not just access but creation. Technology hands down the power to craft intricate narratives and dazzling visuals without requiring a studio’s resources. Software like Photoshop and Procreate allow for experimentation with line, color, and texture that old masters could hardly dream of. Yet, this ease of creation also floods the market. Standing out requires not just talent but an adeptness with social platforms and branding unheard of in bygone days.

However, this digital dawn isn’t without its shadows. The tactile pleasure of turning pages and the collectibility of print editions hold an enduring allure. Print and digital formats often are portrayed as dueling pistols at dawn, but they need not be. They can coexist in a symbiotic relationship, each feeding the other. Limited print runs of popular webcomics serve as tangible trophies for devoted fans, while digital platforms act as testing grounds for what might next hit the shelves.

Creators face a tightrope walk between these worlds. The balance lies in leveraging digital’s reach while nurturing the intimate connection print offers. Events like Comic-Con showcase how fervent fans are for that close encounter, be it through autographed editions or face-to-face dialogues with creators.

The challenge ahead lies not just in audience engagement but in economic sustainability. Monetizing content in a freemium culture demands innovation. Strategies range from Patreon’s patronage model to exclusive content for subscribers, reflecting a shift towards direct support from readership communities rather than traditional advertisement revenues or sales alone.

For readers, the digital era ushers in a golden ticket to explore vast universes from anywhere at any time. For creators, it presents a labyrinth of opportunity and pitfalls, rewarding those who can navigate this new realm with a mix of creative prowess and savvy digital strategy.

As we look ahead, the crystal ball remains cloudy on the full impact of digital on comics and graphic novels. Still, one thing stands clear: the sequential art form that has evolved from cave paintings and hieroglyphs will continue to adapt and thrive. It’s a testament to the undying human urge to tell stories, now armed with digital tools that promise to push this primeval craft into a thrilling future.

In the grand tapestry of storytelling, the enduring allure of comics and graphic novels stands as a vivid reminder of our intrinsic desire to share stories. As we continue to witness the evolution of this art form through digital innovation, it’s clear that the essence of sequential art—forging connections through images and text—remains an unbreakable thread in the fabric of human expression.