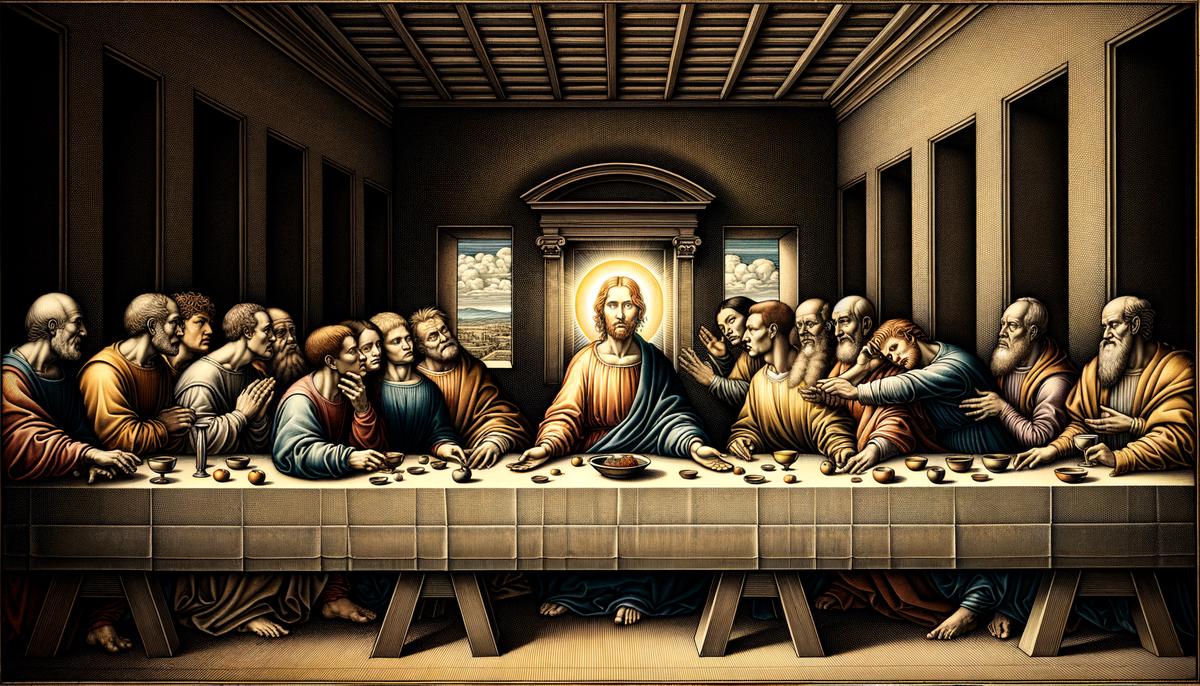

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper holds a mirror to the intricate dance of symbolism and mystery, inviting onlookers into a silent conversation spanning centuries. Each brushstroke and shadow cast by the figures on the canvas whispers tales of intrigue, beckoning scholars and art enthusiasts to lean closer, listen, and perhaps, decode the silent messages left by the master himself. As we traverse through the corridors of art history, we find ourselves standing before not just paintings, but portals to the minds of their creators, offering a glimpse into the confluence of science, religion, and philosophy that shaped their world.

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper is a treasure trove of symbolic elements and mysterious cues that point to various interpretations and theories. Every character in the painting, the objects on the table, and the background details work together to spark discussions among scholars, art lovers, and conspiracy theorists alike.

One attention-grabbing element is the positioning of the characters. Notice how they’re grouped in threes, a number often associated with the Holy Trinity in Christian symbolism. This deliberate choice by da Vinci suggests a deeper layer of meaning, inviting viewers to ponder the significance of the grouping.

In addition, the enigmatic figure seated to Jesus’s right has stirred significant debate. Some argue that this is John the Apostle, as traditionally interpreted, due to the character’s youthful appearance and feminine features. However, others propose a more controversial theory: the figure is Mary Magdalene, which hints at a secret marriage between her and Jesus. This theory challenges conventional narratives and fuels discussions on the real story behind The Last Supper.

Another intriguing aspect is the angle and position of Jesus’s arms and hands, which form a triangle, again possibly representing the Trinity. The shape of his body and the space around him might also be interpreted to resemble a womb, suggesting birth or creation, adding another layer of mystique to the painting.

The mysterious hand holding a knife, appearing to float unattached from any body, has also aroused curiosity and speculation. This detail has been interpreted as a sign of betrayal and violence looming over the scene, a foreboding symbol that complements the tension depicted among the figures.

Speculation extends to the items on the table. Some researchers dive into the analysis of the bread and wine, drawing parallels with the Eucharist and interpreting their placement as symbolic of Jesus’s sacrifice. Others examine the types of food depicted, debating their significance and whether they correspond to specific biblical references or cultural practices of the time.

Noteworthy too is the inclusion of certain elements in the background and architecture that some believe may encode mathematical and astronomical information. This aligns with da Vinci’s well-known love for incorporating such knowledge into his art. For example, the alignment of the windows and the presence of natural light are scrutinized for potential hidden messages about celestial configurations or significant dates.

Sifting through these layers of symbolism, The Last Supper is a prime example of how art can serve as a multifaceted historical document. It encapsulates interpretations across art history, theology, and conspiracy theories, making it an evergreen subject of analysis and debate. Through these discussions, what emerges is a dynamic narrative that keeps The Last Supper as relevant and intriguing today as it was in the 15th century.

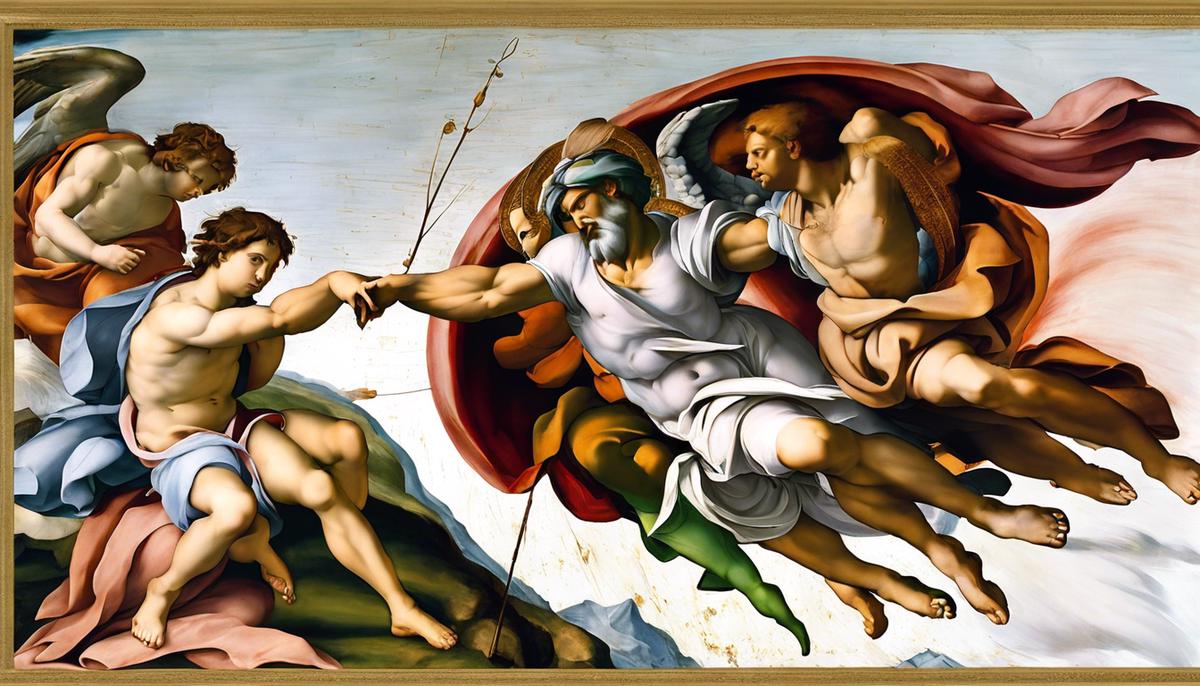

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo

Shifting focus to another equally renowned masterpiece by Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, a closer look reveals layers that transcend its apparent beauty to hint at the artist’s deep anatomical knowledge. Much speculation has centered around the figures and shapes that envelop God and Adam, suggesting these might mimic the intricate structure of the human brain. This idea gains traction considering Michelangelo’s well-documented fascination with human anatomy, a common pursuit among Renaissance artists driven by a revival of interest in the classical human form.

Art historians have meticulously pieced together evidence indicating that Michelangelo may have intended to embed an anatomical code within the fresco. Detailed analysis points to the striking resemblance between the shape enclosing God and a sagittal view of the human brain. Key elements in this anatomical parallel include the Sylvian fissure, represented by the cloak-like shape around God, and parts of the brain like the cerebellum, optic chiasm, and pituitary gland mirrored in the figures and postures of the angelic beings surrounding Him.

Neuroscientists have added credibility to this theory, stating that the accuracy with which these anatomical features are hinted at comes from someone intimately familiar with dissection. This observation aligns with known records of Michelangelo performing dissections to better understand muscle and bone, lending him the capability to accurately represent human anatomy in his art.

Perspectives from Renaissance studies scholars provide a broader cultural context, suggesting that this hidden message reflects the period’s blend of art, science, and spirituality. They argue that embedding such anatomical detail within a religious scene could symbolize the divine spark within human intellect and creativity, an idea celebrated during the Renaissance.

This analysis not only deepens our appreciation of Michelangelo’s skill and intellect but also reinforces the Renaissance’s legacy of intertwining art and science. Discovering potential anatomical symbolism in The Creation of Adam invites viewers to ponder not just the painting’s beauty but also the breadth of knowledge and curiosity that fueled its creation.

The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger

Turning our gaze to The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger, we immediately notice the anamorphic skull, a striking feature that commands attention for its peculiarity. Placed near the bottom of the composition, this skull can only be viewed correctly from a sharp angle to the side of the painting. Its inclusion is no random choice; instead, it serves multiple layers of meaning within the opulent setting of the artwork.

The skull stands as a powerful memento mori, a reminder of mortality that juxtaposes the magnificent display of wealth, knowledge, and worldliness embodied by the two ambassadors. Amidst the luxurious fabrics, intricate scientific instruments, and symbols of power and faith, the skull whispers the inevitability of death, suggesting that such worldly achievements are transient.

Art historians often interpret the skull’s anamorphic distortion as symbolic of the period’s profound fascination with vision, perspective, and the limits of human perception. This innovative representation was not only a display of artistic skill and intellect but also spoke to the shifting paradigms of the Renaissance, where the quest for knowledge was in constant tension with the teachings of religion.

By integrating the skull in such an unexpected manner, Holbein captures the essence of the scientific and religious upheavals characterizing the era. The anamorphic skull acts as a visual conundrum, challenging viewers to question their perspectives and acknowledge the depth and multiplicity of truth—a reflection of the period’s investigations into the nature of reality itself.

Experts in optical illusions further expound on how the skull’s portrayal pushes viewers to engage with the work more intimately, inviting them to move and alter their viewpoints for a clearer understanding. This physical engagement mirrors the intellectual challenge of reconciling the themes of faith, science, and mortality.

The tension between worldly successes represented by the ambassadors and the subtle presence of death encapsulated by the skull explores a universal theme: the search for meaning beyond the material world. Despite their accomplishments and vast knowledge, the ambassadors are still subject to the ultimate equalizer—death—reminding viewers of the fragility of human existence and the limits of worldly pursuits in the face of inevitable mortality.

This discerning incorporation of the skull thus enriches The Ambassadors, infusing it with layers of philosophical contemplation that engage themes far beyond its ostensible subject. The piece emerges not only as a portrait of two influential men but as a profound commentary on human existence, prompting enduring questions about life, death, and the pursuit of knowledge amidst the certainties and uncertainties of human life.

Guernica by Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” stands as a monumental beacon of anti-war sentiment, its composition saturated with symbols that scream the unbearable agony of conflict. Within its grand scale, each figure and object is meticulously placed to narrate the story of devastation, a voice against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War’s terrors.

Central to the despair in “Guernica” is the image of the bull, looming over the chaos with a presence as mysterious as it is formidable. Art critics and historians diverge in their interpretations of the bull’s meaning. Some see it as a representation of brutality and darkness inherent in wars, while others argue it symbolizes the resilience of the Spanish people. Picasso himself muddied these waters with varying explanations, leaving a hauntingly ambiguous figure that serves multiple symbolic purposes.

Beneath the bull, the horse convulses, a spear protruding from its side. This depiction of suffering is immediate and visceral, embodying physical and psychological pain that war inflicts upon its victims. The horse, often a symbol of freedom and vitality, is here a specter of death, highlighting the innocence destroyed by violence. According to analysts, the horse’s agony also serves as a stark contrast to the bull’s stoicism, offering a tableau of war’s complex emotional landscape.

Illuminating this turmoil from above isn’t solace but further torment in the form of a light bulb, harsh and artificial. This glaring object has been interpreted as the “bomb” — a literal explosion casting merciless light upon the scene below. Its inclusion by Picasso throws into sharp relief the technological advancements that, rather than progress humanity, had been harnessed to make war more dreadful and lethal.

Art experts often reflect on the dismembered soldier at the bottom of the painting, suggesting that this figure embodies the ultimate sacrifice — the loss of life for one’s country. Around him, fragments of bodies and shattered lives symbolize not only physical destruction but the social and familial disintegration that accompanies war.

A woman cradles her dead child, a scene that draws an emotional line directly to historical paintings of the Madonna and Child, yet perverted into a tableau of grief and loss. This poignant imagery serves to universalize the experience of Guernica, tying it to every time and place where war has torn apart what is most dear to humanity.

Political historians see “Guernica” as an unequivocal statement on the specific event of Guernica’s bombing, yet its potency lies in its undiminished relevance in today’s world. In an era where conflicts continue to ravage communities, Picasso’s masterpiece persistently asks its viewers to confront the desolation wrought by war.

As diverse interpretations continue to add layers to understanding “Guernica’s” impact, its message rings clear through time: war constitutes an unequivocal horror, one that humanity must recognize and strive tirelessly to prevent. Through this masterpiece, Picasso not only immortalizes the specific tragedy of Guernica but also etches a perpetual reminder of war’s universal and timeless anguish onto the canvas of human consciousness.

In the grand tapestry of art history, The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci emerges not merely as a masterpiece of visual storytelling but as a beacon that continues to illuminate the enduring power of art to transcend time and speak to the core of human experience. It is this ability to fuse the ethereal with the tangible, to marry mystery with revelation, that cements its place in the annals of art history. As we step back from the canvas, we carry with us not just the images etched in pigment but the profound reminder of art’s capacity to engage, challenge, and inspire across ages.