Artistic Responses to Revolution

Artistic interpretations of revolutionary turmoil have been a staple in European painting, capturing the societal and psychological impacts of such events through vivid visual narratives. Painters like Jacques-Louis David became instrumental during the French Revolution as active participants. David's iconic artwork, The Death of Marat, goes beyond mere historical recording; it emblematically conveys the pathos of the period. The stark palette and austere composition serve to pronounce the martyrdom of Jean-Paul Marat, aligning with David's support for revolutionary ideals.

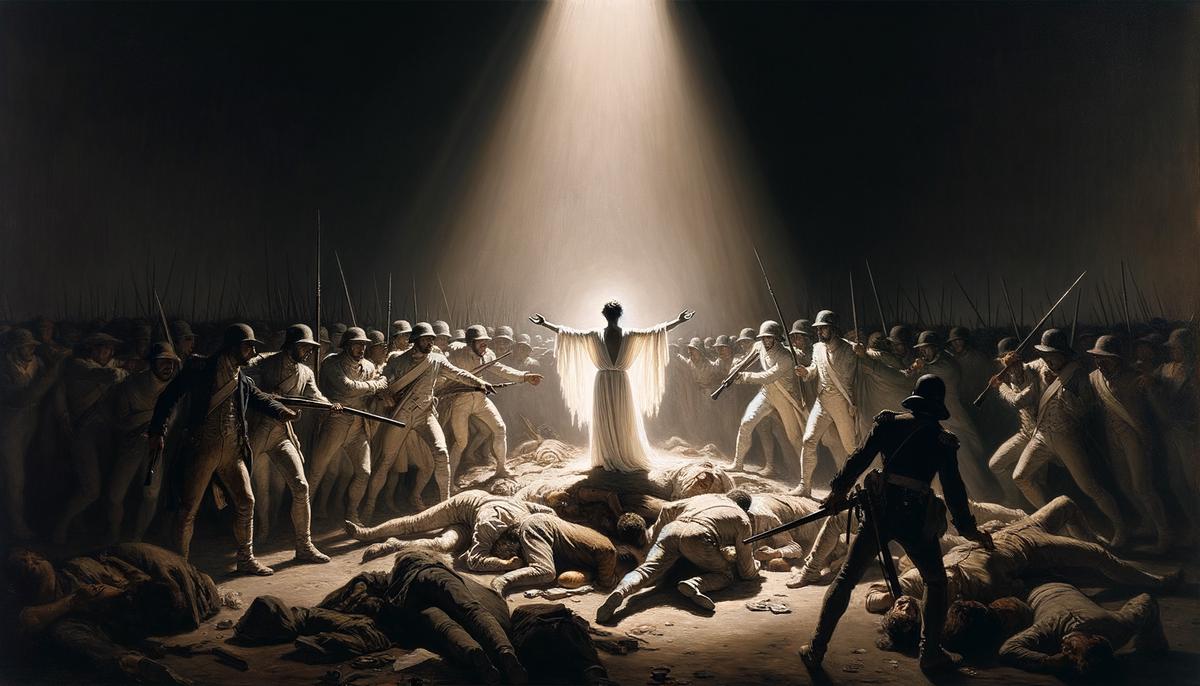

In the 19th century, Romanticism emerged as another pivotal movement addressing the theme of revolution. Romantic artists emphasized emotion and individualism against the backdrop of revolutionary fervor. Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People portrays the 1830 July Revolution with vigor. The allegorical figure of Liberty dominates the canvas, charging forward amid the chaos, embodying the struggle for freedom. Delacroix captures the physical skirmishes and instills a sense of hope characteristic of the Romantic view.

Realism in the latter half of the 19th century approached revolutionary themes differently. Artists like Gustave Courbet aimed to depict scenes truthfully, without romanticization. Courbet's involvement in the Paris Commune and his subsequent artwork reflect this shift. His depictions of ordinary people engaged in real-life struggles presented a raw narrative that diverged from the heroic representations seen in Romanticism.

Honoré Daumier, another Realist, used his art to critique societal injustices and political corruption that often led to revolutionary sentiments. Daumier's lithographs, filled with satirical depictions of political figures and urban life, encapsulate the social criticism that fueled revolutionary ideals. His approach reveals a nuanced depiction of the circumstances leading to civil upheaval.

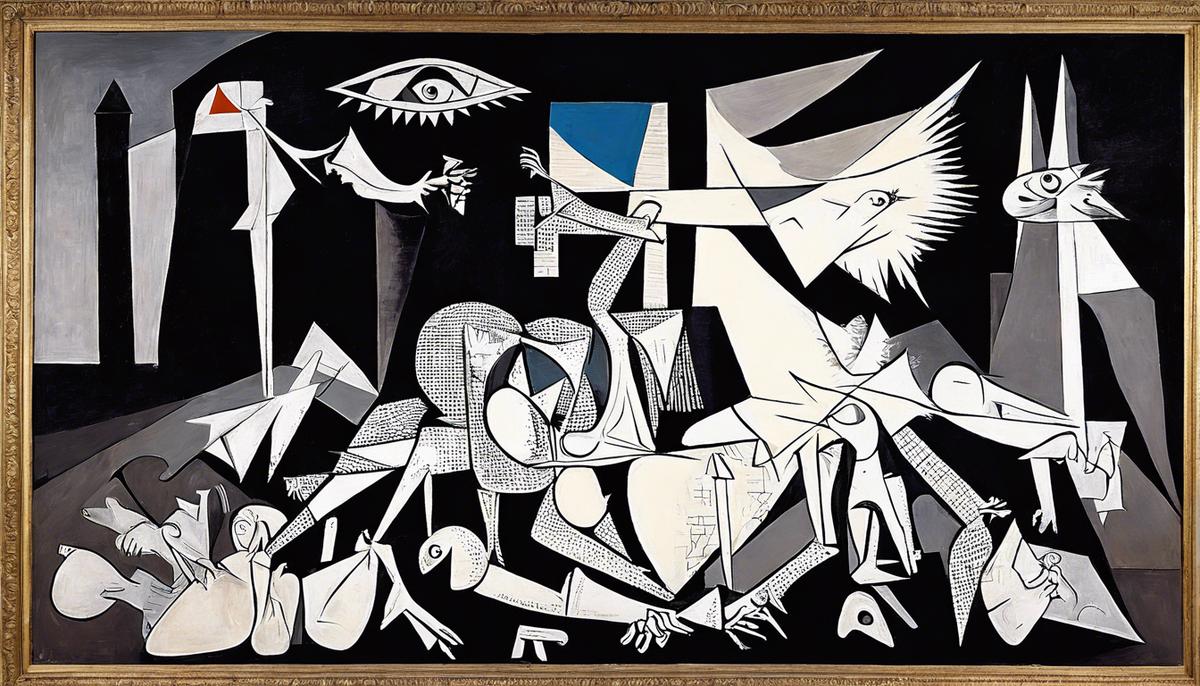

In the 20th century, Expressionism showcased an introspective and emotional reaction to societal unrest and the trauma of World War I through distorted forms and dramatic colors. Painters like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner responded with bold, jarring works that harness an intense response, reflecting the disorienting impact of revolution on public consciousness.

Artists across these diverse movements utilized different approaches to address political and social revolutions, making their artworks a reflection of personal sentiment and a broader commentary on the human condition during times of change. These paintings remain crucial historical documents and poignant reminders of art's power to reflect and influence societal transformations.

Iconography of Rebellion

In European art depicting revolutionary periods, the use of specific iconographic elements emerges as a powerful tool for conveying complex narratives and evoking emotional responses. Colors such as red and black recur frequently, symbolizing blood, conflict, and anarchy, while also hinting at themes of sacrifice and mourning. Delacroix's usage of vibrant reds in the garb of Liberty in Liberty Leading the People draws the eye to the central figure and summons the fiery essence of revolution.

The recurring figures in these paintings, such as the triumphant hero or suffering citizen, serve as poignant motifs that enhance the viewer's emotional engagement. These characters embody the collective spirit or tragic plight of the populace, offering a window into the emotional landscape of the times. The mourning figures in The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David are emblematic of a nation in mourning, reflecting the somber realities of political strife.

The settings chosen by artists to frame these scenes are loaded with symbolic meaning. Barricades, urban squares, and domestic settings become stages where the drama unfolds. These spaces represent either the claustrophobic pressures of urban uprisings or the stark isolation of political exile. The cluttered Parisian streets in Daumier's works contrast with the composed, isolated figure of Marat, emphasizing different aspects of revolution—collective versus individual, public versus private.

Artists employed specific motifs and symbols like flags, broken chains, and barricades which serve as literal elements and are imbued with symbolic resonance. Flags often bear colors representing ideals such as liberty and become focal points around which action swirls. Broken chains signify liberation and the breaking of oppressive systems, resonating with viewers' understanding of freedom.

These iconographical choices reflect a complex mixture of hope, despair, idealization, and realism as artists grappled with their own hopes and disillusionments about the revolutionary movements. Such visual strategies invite viewers to witness and feel the historical moment, bridging temporal gaps and allowing for an empathetic understanding of past events.

These symbols and themes create the emotional tenor and ideological stance of the artwork, drawing viewers into a visceral experience of revolution. Through this exploration of iconography, we appreciate how art serves as a conduit for collective memory and emotional truth.

Personalities in Revolutionary Art

Napoleon Bonaparte, perhaps the most iconic figure to emerge from the French Revolution, looms large in European revolutionary art. His depiction oscillates between glorification and scrutiny, reflecting his complex legacy. In works such as Jacques-Louis David's Napoleon Crossing the Alps, Napoleon is imbued with an almost superhuman charisma, shown commanding forces, evoking the Romantic hero archetype. This idealized representation aligns with the public's perception of him as a decisive, magnetic leader who shaped modern Europe.

Other depictions delve into more critical explorations of his role. In less glorified portrayals, artists hint at Napoleon's authoritarian drift and the eventual disillusionment of many who initially saw him as a harbinger of liberty and justice. The complexity of his character and the consequences of his policies are nuanced, inviting a reconsideration of his actions and their impact.

Jean-Paul Marat, immortalized in David's The Death of Marat, epitomizes the tribulations of political martyrdom. David immortalizes him—quill in hand and wound exposed—transmitting the aura of a secular saint. This portrayal sparks debates about the boundaries between personal sacrifice for an ideologically fueled cause and the adulation of such sacrifices, reflecting deep divisions in society's reckoning with its revolutionary heroes.

Marat's contemporary counterpart is the personified figure of Liberty. Rendered by Delacroix in Liberty Leading the People, she strides over the barricades, fearless and resolute, encapsulating the revolutionary spirit. Unlike the portrayals of Napoleon or Marat, Liberty is an allegorical figure, representing an ideal. She holds the tricolor flag, leading a charge that includes figures from all walks of life, symbolizing unity in pursuit of freedom and equality. This imagery projects a universality that is inspirational, positioned against the grim historic realities of these revolutions.

These personifications actively mold public perception and historical memory. Through such art, figures like Napoleon are critiqued and celebrated, their legacies subjected to the interpretive visions of artists who grapple with their era's complex social currents. Similarly, the varying renditions of Marat present ongoing engagements with the consequences of revolutionary zeal.

Whether aggrandizing or critical, these artistic depictions shape and are shaped by the cultural temperaments from which they arise. They offer more than mere historical recount; they provide a narrative that participates in the ongoing interpretation of European revolutions. This continual artistic dialogue ensures that our understanding of these periods remains as dynamic and layered as the events and personalities themselves.

Evolution of Revolutionary Narratives

Throughout the ages, the depiction of revolutions in European art has continually evolved, reflecting shifts in societal values, historical perspectives, and artistic modalities. Initially, as seen in works like David's The Death of Marat, art served almost as a contemporaneous form of journalism, capturing dramatic events as they unfolded while also imbued with propagandist underpinnings to sway public opinion. These works were immediate and visceral, with a direct tie to the events they depicted—a melding of political fervor with vivid aesthetic choices meant to evoke emotion and support for the cause.

Moving into the 19th and early 20th centuries, interpretations began to change. Artists like Delacroix still dealt with the rhetoric of revolution but infused it with romanticized ideals, signaling a shift from literal interpretations to more symbolic representations. The technique became less about documenting and more about invoking the spirit of revolution—its ethos rather than its chronology. The idealization of subjects like Liberty personifies this shift, embodying abstract ideals rather than specific moments or figures.

In contemporary times, the shift has morphed into a diverse array of interpretations that challenge previous narratives or extend them into new contexts. Modern and postmodern artists are revisiting revolutionary themes with a critical lens that often interrogates the legacy and outcomes of these upheavals. For instance, the work of artists like Banksy employs irony and paradox, using modern tools and pop culture formats to question the sanctity and fallout of revolutionary ideals, capturing the disillusionment or complexity in their outcomes. This contrasts with the clear heroics and defined villains often present in older depictions.

Techniques in modern revolutionary depictions also reflect broader trends in art in their diversity and innovation—digital media, installations, and performance art offer new ways to experience and interpret the tumult of revolutions. These forms allow for a multisensory approach and engage with audiences on various interactive levels, from global participatory projects to virtual reality experiences, expanding the narrative scope beyond traditional canvases.

The influence of contemporary political and cultural contexts can't be understated. In an era dominated by rapid media dissemination and global interconnectedness, revolutionary images are consumed and influenced by an international audience, broadening the dialogue around these events. This global perspective often infuses the work with diverse political and cultural messages that transcend local origins and speak to universal themes of struggle, power, oppression, and the human condition.

This evolution reflects the development of artistic techniques and modalities and delves deeper into the human psychology behind revolutions. By exploring how these tumultuous events are remembered, interpreted, and reinterpreted over time, art not only chronicles historical shifts but participates in the ongoing discourse of what revolution means within the human narrative. As such, contemporary depictions will likely continue to evolve, adding layers of complexity and perspective to our understanding of past and present revolutions. This conversation between art and revolution remains as dynamically unfolding as the historical events that first sparked them, continuously challenging us to reconsider what we know about these transformative movements.

The continuous interplay between art and revolution encapsulates more than mere historical documentation; it actively shapes our perception of these transformative periods. By examining the myriad ways in which artists have responded to societal upheavals, we gain a deeper appreciation of both the emotional and ideological impacts of revolutions. This dialogue between past and present ensures that our understanding of these events remains as dynamic and multifaceted as the artworks that depict them.

- Clark TJ. Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution. Princeton University Press; 1982.

- Crow T. Emulation: David, Drouais, and Girodet in the Art of Revolutionary France. Yale University Press; 2006.

- Eisenman SF. Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History. 4th ed. Thames & Hudson; 2011.

- Rubin JH. Realism and Social Vision in Courbet and Proudhon. Princeton University Press; 1980.