(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1525-30

Died: 1569

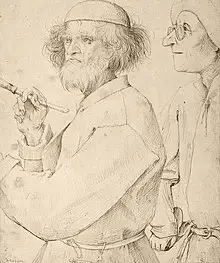

Summary of Pieter Bruegel the Elder

When it comes to art, Pieter Bruegel, the Elder is a Renaissance artist known for his visually captivating paintings that celebrate humanity, in contrast to the pious religious painting that predominated Renaissance art of the previous century. This 1520s Dutch painter is best known for his depictions of rural working life, religion, and superstition, and the political and social intrigues of his day. He was born in what is now the Netherlands. An unmistakable sense of humour, an interest in the collective rather than the individual, and a healthy scepticism for tales of great deed and men were all present in these works. When a painter debunks mythology, he or she is in the spirit of “Peasant Bruegel” who is sometimes referred to as the Dutch Golden Age painter of the following century.

Art historians credit Bruegel with inventing narrative composition, in which an expansive landscape is overrun with hordes of people, all of whom are clustered together to create multiple interlocking focal points. This approach set Bruegel apart from many Renaissance artists who preferred more visually harmonious compositions, offering a snapshot of a lingering mediaeval view of human society as chaotic and unruly. It is reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch’s surreal hellscapes.

A series of mythological or historical paintings by Bruegel, in keeping with his preference for large group compositions, focuses on the everyday life going on all around the nominal subject. Only a pair of legs sinking into the water in the middle distance in his Landscape with the Fall of Icarus record the tragic hero’s downfall. This is a departure from Renaissance art’s focus on heroic figures and suggests a sympathy with humanity’s common lot, which artists and writers have recognised ever since.

As a pioneer of “genre painting” Bruegel depicted scenes of everyday life with honesty, empathy, and a touch of slapstick. While he is reluctant to pay homage to Biblical and mythical heroes, he has no qualms about portraying peasants at a wedding or a procession of blind beggars. Throughout the years to come, this focus on the everyday would be used as the foundation for the artistic ethos known as Realism.

Childhood

Pieter Bruegel’s childhood is largely unknown, despite the fact that he is widely regarded as one of the greatest artists of the Northern Renaissance. All that is known about Peeter Brueghel’s life is that he was born sometime between 1525 and 1530 in or near Breda, the Netherlands, into a family that many believe was rural in nature.

Early Life

An apprenticeship with Pieter Coecke van Aelst, a Flemish artist, was part of Bruegel’s early training. He moved to Antwerp after Van Aelst’s death in 1550, where he was hired to assist in the creation of a three-panel altarpiece for the guild of glovemakers. As a result of his election to the Guild of St. Luke in Antwerp in 1551, Bruegel’s professional life began in a significant way under the guild system.

Mid Life

When he left Antwerp in 1552, Bruegel went on a long painting and research trip to Italy. In spite of his lack of formal training in Italy’s Renaissance style, the countryside he visited had an enormous impact on the young artist, who would go on to become famous for landscape paintings. Bruegel’s journey home through the Swiss Alps was of particular significance. He “swallowed all the mountains and rocks and spat them out again as panels on which to paint, so close did he attempt to approach nature in this and other respects.” according to his first biographer Karel van Mander.

In 1555, Bruegel returned to Antwerp and began working as an engraver for the Dutch artist Hieronymus Cock. Bruegel was known as “Pieter the Droll” because of the humorous themes and motifs he used in his engravings for his employer. Van Mander tried to sum up Bruegel’s engaging personality by describing the artist as a “charming” individual “a stoic and cautious individual. With few words, but an uncanny ability to surprise people with his clever jokes and noises, he was one of society’s funniest men.”

Engravings and paintings from the middle period of his career have been compared to Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch because of the complex, fantastical scenarios depicted in them (c. 1450-1516). Cock profited from this reputation by selling a relatively unknown Bruegel engraving, Big Fish Eat Little Fish (1556), as a Bosch original in order to get a higher price for the piece (Bosch had in fact died 40 years before the work was created).

Late Life

In spite of the fact that he is best known for his paintings, Bruegel didn’t begin painting until around 1557. To avoid comparisons with older Norther Masters like Bosch, he developed his own distinct compositional style at this point, allowing him the opportunity for a significant and in-demand career as an artist. Commissions were flooding in from wealthy merchants and church members, especially in the first half of the year. He changed the spelling of his name from “Peeter Brueghel” to “Pieter Bruegel.” in 1559, when he was just 17 years old.

When he married Mayken Coecke in 1563, he married the daughter of his former teacher Pieter Coecke van Aelst. The artist, in his thirties, and his bride, who he had known since she was a child, had a significant age difference. In the year of their marriage, there was some speculation that Mayken’s mother had asked the couple to relocate to Brussels in order to stop Bruegel from having a flirtatious relationship with a maid. According to some accounts, Bruegel marked a stick with a notch every time his maid told a lie. The extent of their relationship is unknown, but there are stories of humorous interactions between the two. Bruegel was said to have run out of space on his stick because of her deception.

When Pieter, later known as Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Jan, later known as Jan Brueghel the Elder, married Bruegel, the couple began an artistic dynasty that included the couple’s two sons. In the years after the elder Bruegel’s death, his son Pieter would go on to produce many copies of his father’s paintings, ensuring their international reputation, but also resulting in doubt as to whether certain compositions were actually the work of father or son.

Late in his career, Bruegel produced a number of works depicting religious stories and everyday life. Art historians have debated for centuries about the meaning of certain works thanks to the impact of the latter. It is not uncommon for early critics to view Bruegel’s paintings as humorous depictions of the lasciviousness and promiscuity of the lower classes. Bruegel, on the other hand, has been interpreted in recent years as attempting to elevate that class by depicting them in a celebratory light. Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, two art historians, put it this way: “that he would even consider such a thing worthy of depiction sets him apart from nearly all of his contemporaries For the Italians and Romans, it was important to emphasise what set man apart from other species. Although they share many characteristics, their similarities are emphasised by Bruegel.” He adds that “Bruegel’s vivid and lusty depictions of rural life can be seen as forming part of a growing sense of national identity.” and William Dello Russo agrees.

Because Bruegel lived during a time of political turmoil, his work has been interpreted in many different ways by scholars. The Hapsburg dynasty ruled over a series of provinces in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, collectively known as the Low or Netherlandish Countries, in the mid-1500s. Spain’s King Phillip II attempted to impose a stricter form of Catholic rule in 1556, sending Duke of Alba to lead a brutal military campaign to suppress Protestant rebellion in Brussels. Even though Bruegel’s work is heavily religious in tone and subject matter, art historian Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen argue that the artist’s refusal to depict Catholic saints and martyrs can be seen as a coded rebuke of the Counter-bloodthirsty Reformation’s campaigns. It is said that Bruegel asked his wife to burn some of his works just before his death because he feared that their content might put her in danger. Bruegel was aware of the political significance of his work.

Bruegel’s death is unknown, but in 1569, the city council of Brussels released him from the obligation of working with a guard of Spanish soldiers stationed in his home, which indicates that the politically subversive content of his work was well understood. However, it is impossible to rule out a more sinister explanation for Bruegel’s death because no paintings from this year have been found. In any event, Bruegel’s early death must be considered one of the greatest tragedies of Renaissance art history.

A significant break from the popular Italian Renaissance style is seen in the work of Pieter de Bruegel, who, unlike the previous century’s Mediterranean masters, preferred to focus on landscape and everyday life rather than grand narrative. Thus, he contributed to the development of a Northern Renaissance style that influenced artists such as Peter Paul Rubens and Rembrandt in the subsequent centuries.

Modern art has been influenced by Bruegel’s paintings. Critical Wilfried Seipel says that Bruegel’s paintings “form a cycle, indeed an epic of human existence in its helplessness not only in the face of nature but also when confronted with the seemingly immutable course of world history” beyond “psychological and iconological interpretation and independent of biographical and contemporary historical preconditions.” To the Dutch Golden Age artists of the following century, Bruegel’s decision to depict common people in everyday domestic scenes was a stepping stone, and it also predicted the socially conscious Realism and Naturalism of the mid-to-late nineteenth century, including the work of Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, and the Russian Peredvizhniki School. William Carlos Williams dedicated a ten-poem cycle to Bruegel’s egalitarian vision in his final collection, Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems, during the twentieth century (1962).

Famous Art by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

1558

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, one of Bruegel’s most famous works, depicts a landscape in the foreground and a vast seascape in the background. A farmer with a plough and a horse is the closest to us. A shepherd is tending to his flock on a lower plateau of land to the right of him. While a fisherman casts his net at the water’s edge, two legs kick in the air in the bottom right: a comically minute reference to the titular narrative, which therefore seems to unfold in the background of this scene.

The Fight between Carnival and Lent

1559

This painting by Bruegel shows the customs associated with two early modern festivals that were closely aligned in the calendar in an allegorical representation of the competing drives that underlie human character. As you look to your left, you’ll see the Carnival figure, which is depicted as an obese man riding on top of a beer barrel while roasting an entire pig and donning nothing less than an entire meat pie as a headdress. In his throne, he watches over an encampment of revellers, thieves, and beggars. In defiance of his more lavish offerings, the gaunt figure of Lent, dressed as a nun, extends a platter of fish to the right. People in hoods emerge from the church’s archway behind her, their artwork shrouded in the custom of fasting during Lent. As for the other side of the canvas, the tavern represents the vices and pleasures of the flesh in a similar fashion.

The Netherlandish Proverbs

1559

In this painting, you can see Bruegel’s mastery of complex composition, often based on strong diagonal lines that bring overall cohesion to a large number of intersecting focal points. Many bizarre and superstitious practises take place in the fictional village depicted in The Netherlandish Proverbs.

The villagers’ actions are based on approximately 120 Dutch proverbs, all of which deal with the peculiarities of human behaviour. Foreground: A man bangs his head against a brick wall, representing the tendency of a fool to keep trying the impossible; background: A figure weeps over a pot of spilt porridge, reminding the viewer that actions taken are irreversible. Bruegel is known for his complex compositions, which feature numerous groups of people engaged in small interactions. Often satirical or didactic, these individual compositions establish an overarching theme that has had a profound impact on the history of art. An allegory of Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1888) and The Baths at Ostend (1890) by Dutch Symbolist and Expressionist James Ennor, for example, show the influence of Bruegel’s allegorical tableaux (1890).

The Tower of Babel

1563

An enormous partially built tower dominates Bruegel’s extraordinary 1563 painting, The Tower of Babel. It is surrounded by a landscape of tiny figures, some of whom march around its curving stories, while others work at the scaffolds on its sides.. Right, ships unloading building materials are depicted in all their fine, realistic detail.

The Hunters in the Snow

1565

Three hunters and their dogs make their way through a picturesque, sprawling village in a snowy landscape. On the left side of the composition, vivid tree silhouettes lead the eye toward the busy scene at the centre, a happy gathering of people on a frozen river. Under a sky of blue-gray winter, buildings and snow-covered mountains can be seen in the distance.

The Wedding Dance

1566

Peasant marriage in Bruegel’s life-affirming painting features an overflowing crowd of happy, inebriated revellers. There’s a buffet in the foreground, and guests are dancing, drinking, and kissing in an unruly circle that occupies the composition’s central space. Even though he is a part of the happy spiral, the figure to the right in a black hat and orange shawl appears detached from the scene, leading some critics to speculate that he is a self-portrait of the artist.

The Conversion of Paul

1567

The Conversion of Paul, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, features a mountainous forest landscape. Crowds of people, including a number of soldiers in armour, swarm into a gap in the rockface from the centre foreground to the right background. A serene body of water can be seen in the left background, hidden behind the mountain’s crest.

The Blind Leading the Blind

1568

In the centre of this painting, five blind men trudge along, canes in hand, their arms outstretched for help. There is already one member of the procession lying on his back in the dirt after he fell. As he watches the man directly behind him stumble, it’s clear that the four people following him will do the same. A church steeple, low thatched roofs, and a curving, tree-lined hillside are all visible in the background, which is typical of Bruegel’s landscapes.

The Magpie on the Gallows

1568

This painting from Bruegel’s penultimate year depicts a lush woodland scene. a Dutch village’s gable and tiled roofs can be seen in the background, while in the foreground, young peasants are seen playing in the fields to the left, unaffected by the structure to their right, perched by a single magpie.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- When it comes to art, Pieter Bruegel, the Elder is a Renaissance artist known for his visually captivating paintings that celebrate humanity, in contrast to the pious religious painting that predominated Renaissance art of the previous century.

- This 1520s Dutch painter is best known for his depictions of rural working life, religion, and superstition, and the political and social intrigues of his day.

- A series of mythological or historical paintings by Bruegel, in keeping with his preference for large group compositions, focuses on the everyday life going on all around the nominal subject.

- As a pioneer of “genre painting” Bruegel depicted scenes of everyday life with honesty, empathy, and a touch of slapstick.

- Throughout the years to come, this focus on the everyday would be used as the foundation for the artistic ethos known as Realism.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.