Foundations of Cubism

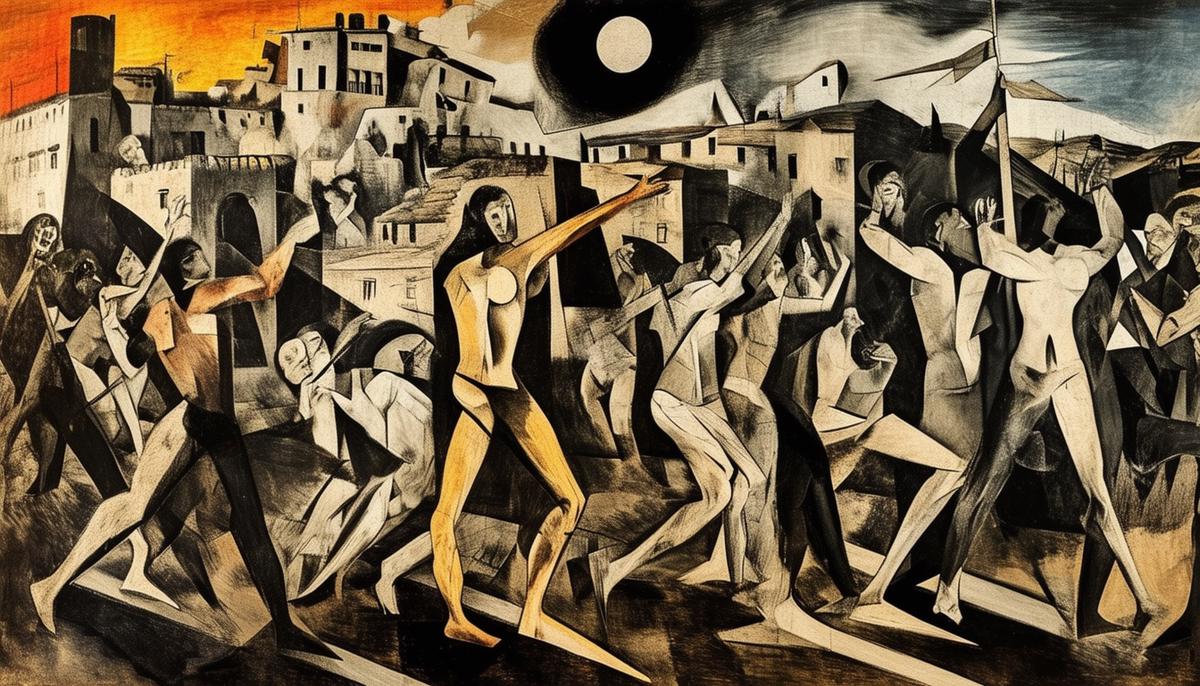

Pablo Picasso, alongside Georges Braque, pioneered Cubism, an art movement that radically changed the course of modern art. This artistic philosophy rejected traditional perspectives that dominated European painting for centuries, introducing a fractured, abstract form depicting the subject from multiple angles simultaneously.

The roots of Cubism trace back to 1907 with Picasso's audacious work, 'Les Demoiselles d'Avignon'. Marked by jagged edges and disjointed human figures, this painting confronted viewers with a shocking departure from reality, serving as a dramatic pivot to abstraction within Western art. The piece fragmented the female form using sharp, geometrical shapes and dabbled with influences from African tribal masks, showcasing Picasso's knack for weaving different cultural aesthetics into modernist viewpoints.

Venturing into Analytic Cubism, Picasso and Braque further dissected and analyzed forms. Common themes and objects were depicted from multiple perspectives in a single artwork, allowing them to focus on probing the structure and forms of everyday objects instead of clinging to illusionistic traditions of depth and perspective.

Synthetic Cubism followed, a slightly more forgiving and decorative apex of their collaborative exploration. This phase saw Picasso constructing paintings by superimposing colored paper cutouts, cloth snippets, and other mixed media onto the canvas, often presenting joyful, bizarrely shaped phantoms of pre-war elegant society.

A standout piece from this period is 'Still Life with Chair Caning' (1912), where Picasso incorporates oilcloth printed with a chair caning pattern, encircled by a rope. This innovative use of materials signified a breach from traditional artistry, inserting bits of the real world onto the canvas plane and muddling the viewer's understanding of art and object.

While the duo moved Cubism through thought and canvas, it served as an academic shell game at times—a cerebral exercise mimicking the splintering society found in early 20th-century Europe. A period characterized by rapid modernization and crumbling old world empires was reflected through every fractured tableau and bizarre intersecting plane Picasso touched.

To grasp a full picture of Cubism, analyzing its echoes within other realms of creative expression reflects its vast influence. This shift shook the visual arts and nudged forward thinking across literature, design, and music, encapsulating an epoch rife with innovative currents.

Picasso's role and techniques in Cubism reveal an intellectual rebellion against singular narrative views in art, promoting a myriad vision more reflective of real-life dynamism and complexity. His works and methodologies endure, and studying them continues to offer insightful perspectives into the fragmented beauty revolutionary minds like Picasso envisioned in their quest to visualize beyond forms.

Picasso's Blue and Rose Periods

Picasso's Blue and Rose periods stand out as profoundly introspective phases that marked his early entrance into the avant-garde frontiers of the art world. During the Blue Period, from 1901 to 1904, a wave of melancholy washed over Picasso's palette, coinciding with the sorrowful episode following the suicide of his close friend, Carlos Casagemas. This tragic event plunged Picasso into a deep contemplation of human suffering, loneliness, and despair, which permeated his artworks.

Scenes of forlorn figures such as beggars, street wanderers, the elderly, and the blind began to populate his canvasses. "The Old Guitarist," painted in 1903, epitomizes this period with its hues of monochromatic blue and indigo casting a somber mood, accentuating the emaciated figure of an old man holding a guitar, metaphorically rich with themes of resilience amidst adversity.

During this time, Picasso honed the emotional potential of colors and embraced a mastery in portraying human fragility. His focus on marginalized individuals possibly questioned societal neglect and offered a discourse on the socio-economic issues of his time. The profound expressions of human emotion spoke directly to observers, asking for empathy rather than serving mere aestheticism. The artworks reached into zephyrs of blue shadow, pulling viewers into contemplations on coldness and isolation.

Transitioning into the Rose Period around 1904 to 1906, a noticeable metamorphosis occurred in Picasso's life and art, lightening his canvas and mood with more upbeat hues of orange, pink, and red. There was a distinct shift away from the piercing coldness of blue to the warmth suggestive of a rosier, hopeful state of mind. The canvases of this period are populated with harlequins, circus performers, and carnival scenes, proposing a lyrical, somewhat romantic vision of bohemian life. This change in subject matter might suggest Picasso's adaptation to his new life in Montmartre, an area teeming with circuses and entertainments where he likely found reprieve in a lively cultural milieu.

His resonance with the performers can be attributed to their parallel lives as societal outliers. "Family of Saltimbanques" ("Family of Acrobats" with Harlequin) from 1905 embodies this period's essence. The use of pinks and earth tones soothes the striking blues, embedding the painting with an intimate, yet existential silence among the figures portrayed, who seem suspended in a transient life between cheer and latent disenchantment.

This oscillation between his Blue and Rose periods underscores a deep engagement with human emotions. Picasso's exploration through these personal phases powerfully depicts how external events antiquated internal states and stirred his artistic narrations. Even as he veered into groundbreaking cubism after these periods, one could trace the roots of his spatial dissonance to the emotional dimensions explored in these earlier works—each subject and stroke carrying a segment of Picasso's young artistic ambitions, reshaping anew both form and empathy amidst the vivid colors or draped blues within his continuous structural rupture.

Global Influence and Legacy

Driven by the seismic shifts introduced through Cubism and his earlier periods, Picasso's influence permeated vast geographical and cultural boundaries, reshaping the art world globally. His reach extended far beyond Europe, profoundly impacting artists across various continents who grappled with similar issues of modernity, representation, and abstraction.

In Africa, Picasso's fascination with African tribal arts, particularly visible in the stylized, mask-like depictions in "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon," was mirrored by a 're-discovery' of his techniques within African modernism. Though Picasso never stepped foot on African soil, his ceremonial and expressive abstraction found echoes in the work of several African artists who saw in Cubism a method to revisit and redefine their cultural and artistic heritage. Uzo Egonu, an influential Nigerian painter and printmaker who lived in Britain, exemplified this reciprocal influence—creating work deeply entrenched in his dual heritage but reflective of the distortive-geometric style pioneered by Picasso.

The breadcrumb trail of Picasso's influence across Africa maps out an interesting confluence where European modernist tactics were appropriated and localized to fit different indigenous narratives. This is particularly evident in how Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi amalgamated Picasso's strategies of abstraction with Islamic calligraphy and African tribal motifs to discuss spirituality and conflict, creating art that transcended time and place, loud with historical echo and visual impact.

Crossing over to the Arab world unveils another textured landscape of influence. The mesmerizing dance between Picasso's techniques and Arab art narratives is palpable in the formation of the Baghdad Modern Art Group by Jewad Selim and Shakir Hassan Al Said in 1951. They declared Picasso "the artist of this age," appreciating the kinship between Picasso's abstracted forms and the layered folklore native to Middle Eastern culture. Through art manifestations in politically-charged arenas, Picasso's signature style infiltrated methodologies of resistance in artistic sentiments during significant historical upheavals.

Swiftly leaping continents to Asia amplifies this continuous thread of impact, where Japanese artist Taro Okamoto declared that meeting Picasso's Guernica changed his life. Taro's works thence buzzed with an aggressive, anti-war sentiment distinctly mimetic of Picasso's piercing visual commentary on conflict, reciprocating a mutual disdain for war's brute consequences showcased within textured canvases sharing screams against oppression.

Searching for these threads acclimates us to Picasso's role within the furnace of Modern Western Art and within the tapestry of a conjoined global dissent against traditional normatives. Every smile etched by his salsa dance of colors and shapes or grimace forged by distorted forms swirling on canvases tells a story much grander than the sum of artistic scrutiny—they hint at societal reconfigurations, an ongoing dialogue between the artist and his broader influence on cultures dynamically tethered yet wonderfully unique. As these strands weave through continents and narratives groove and pivot around Picasso's touchpoints, we see a precursor to dialogues that would steer narratives centuries hence.

Artistic Innovations and Techniques

Picasso's artistic techniques and explorations into collage, form, and color significantly expanded and sometimes shattered the established paradigms of visual art. He embarked on an unparalleled exploration of mediums and styles that defied easy categorization and consistently pushed against the constrictive boundaries typically expected in the art world.

The invention of collage marked a dramatic shift in the understanding of what could be incorporated into artworks. With pieces like "Still Life with Chair Caning" (1912), Picasso moved beyond traditional paint on canvas, incorporating oilcloth printed with a chair caning pattern and even a tactile piece of rope framing the composition, adding multiple dimensions to the piece. This physically evolved the texture and depth of the artwork and challenged the viewer's perspective on what constituted art.

Picasso revolutionized the use of form in his Cubist experiments, embarked upon with George Braque. By breaking objects and figures down into fragmented geometrical forms and rearranging them on flat planes, he offered multiple juxtaposed angles within a single image, forcing a revolution in how form and space were perceived. Not confined to mimetic representation, these fragmented forms suggested a formality more reflective of their intrinsic qualities of shape and interrelation than any adherence to real-life appearance.

This departure was complemented by his radical command of color. While periods like the Blue Period showed restrained use of melancholic hues to evoke deep, thematic gravity, later epochs like his involvement in Surrealism saw a bold juxtaposition of vivid, often unexpected color palettes. Each choice in tint and shading seemed purpose-driven, to evoke emotion, clash with expectation, or guide the viewer's emotional and visual journey through the artwork.

The evolution can also be partially attributed to his daring personal use of materials. Picasso did not shy away from unorthodox material choices — introducing unconventional elements like newspaper clippings, wallpaper scraps, or even three-dimensional objects onto the canvas. Such assemblages questioned established norms about art's construction and broke from entrenched elitism by interspersing everyday, mundane objects with traditional high fine art elements.

Picasso's approach toward Synthetic Cubism further reflects his innovative break from traditional forms. In his synthetic compositions, rather than dissecting forms into smaller parts, Picasso began rebuilding them with broader, more colorful shapes. Using interlocking pieces, he constructed still life or portraits in new vibrant manifestations that no longer primarily sought to dissect form but rather celebrated its lyrical reassembly from abstract elements.

These innovations created a visual vocabulary that transcended visual art itself and leaped into influencing areas such as modern graphic design and structural design elements in architecture. By daring to distort scale, proportion, perspective, and sober reality with inventiveness, Picasso irreversibly widened the narrative capabilities within visual arts.

In venturing away from mimetic representation and moving arts towards an abstraction that interacted with viewers on multiple levels of cognition and emotional response, Picasso didn't just redefine artistic modernism — he crafted a new portal of expression, affirming art not merely as reflective recreation but as elemental, innovative interaction within human cognition and societal parameters. His influence pervades how contemporary artists think about everything from the material potential of their work to the thematic clashing and blending of iconic symbolism and emergent narrative structures.

Picasso's Political and Social Commentary

Pablo Picasso's 'Guernica' stands as one of the most powerful artistic statements against war and violence. Created in response to the bombing of the Basque town Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, this monumental painting is a stark symbol of the devastating effects of conflict.

Measuring 3.49 meters in height and 7.77 meters in width, 'Guernica' presents a haunting scene filled with anguished figures, including:

- A wounded horse

- A grieving woman holding her dead child

- A dismembered warrior

Picasso's use of Cubist techniques, distorting forms and fragmenting space, reflects the shattered lives affected by the atrocity.

The painting's reception was polarizing, with some viewing it as a jarring politicization of art, while others, including progressive artists and intellectuals, saw it as a testament to Picasso's commitment to anti-fascism. 'Guernica' became a universal symbol of protest against wartime atrocities, resonating with peace movements worldwide1.

Picasso's adept use of symbolism, such as the bull representing brutality and the electric light bulb evoking an unfeeling war machine, adds depth to the painting's narrative. The work's international tours rallied support for Spanish Republicans and contributed to broader anti-war sentiment.

While debates have arisen regarding Picasso's political views and engagements, 'Guernica' remains a living interaction of art and activism, its impact felt wherever voices rise against tyranny and oppression. As geopolitical conflicts continue, this masterpiece underscores art's role in bearing witness, reminding, rallying, and potentially repairing.

Picasso's journey exemplifies art's substantial contribution to sociopolitical discourse, challenging viewers and creators to ponder the potential of art to spur change. The enduring significance of 'Guernica' provokes crucial discussions around social and existential questions, echoing past trials while engaging with the poignant tribulations faced by current and future generations.

'Guernica' remains a testament to Picasso's ability to merge profound artistic innovation with poignant political commentary. This masterpiece continues to serve as a powerful symbol of art's role in societal discourse, challenging viewers to reflect on the impact of conflict and the potential of art to influence change2.