(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1839

Died: 1906

Summary of Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne was one of the most famous Post-Impressionist French painter, and he was well-known at the end of his life for urging that painting maintain true to its material, almost sculptural beginnings. Cézanne, also known as the “Master of Aix” after his family birthplace in the south of France, is credited with setting the way for the aesthetic and conceptual development of twentieth-century modernism. In retrospect, his work is the most strong and necessary connection between Impressionism’s ephemeral elements and the more materialist creative trends of Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, and even total abstraction.

Cézanne, dissatisfied with the Impressionist dogma that painting is essentially a reflection of visual experience, set out to create a new sort of analytical discipline out of his creative practise. The canvas, in his hands, becomes a screen on which the artist’s sensory impressions are recorded while he stares intently, and frequently repeatedly, at a specific topic.

Cézanne used a sequence of distinct, systematic brushstrokes to apply his colours to the canvas, as if he were “constructing” rather than “painting” an image. As a result, his work adheres to a fundamental architectural principle: every part of the canvas should contribute to its overall structural integrity.

Even a plain apple might have a sculptural depth in Cézanne’s mature paintings. It’s as if each still life, landscape, or portrait has been scrutinised from several perspectives, and the artist has recombined its material features as no ordinary copy, but as “a harmony parallel to nature.” as Cézanne put it. The future Cubists saw Cézanne as their genuine master because of this feature of his analytical, time-based approach.

Childhood

Paul Cézanne was born in the southern French town of Aix-en-Provence in 1839. Paul’s father was a successful lawyer and banker who pushed him to follow in his footsteps. Cézanne’s final rejection of his domineering father’s ambitions resulted in a lengthy, tense relationship between the two, despite the fact that the artist remained financially reliant on his family until his father’s death in 1886.

He was good friends with Émile Zola, a writer who was also born in Aix and went on to become one of the most important literary personalities of his age. Cézanne and Zola were part of a tiny group known as “The Inseperables” a group of daring artists. In 1861, they both relocated to Paris.

Early Life

Cézanne was a self-taught artist to a considerable extent. He enrolled in evening painting courses in his hometown of Aix in 1859. After relocating to Paris, Cézanne applied to the École des Beaux-Arts twice but was rejected by the jury both times. Cézanne visited the Musée de Louvre frequently, where he copied paintings by Titian, Rubens, and Michelangelo instead of receiving professional training. He also went to the Académie Suisse on a regular basis, a studio where young art students may sketch from a live model for a little monthly fee.

Cézanne met fellow painters Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, and Auguste Renoir at the Académie, all of whom were struggling artists at the time but would soon become founding members of the emerging Impressionist movement.

Cézanne’s early paintings were characterised by a dark hue. The paint was frequently poured in thick impasto layers, which added weight to already gloomy works. Early paintings showed a preference for colour over well-defined shapes and perspectives, which the French Academy and the jury of the annual Salon, where he consistently presented his work, liked. His proposals, on the other hand, were all rejected. In addition, the artist returned to Aix on a frequent basis to get financing from his disapproving father.

Cézanne’s painting underwent a significant transformation in 1870, owing to two factors: the artist’s relocation to L’Estaque in the south of France to avoid the military draught, and his closer contact with Camille Pissarro, one of the most prominent young Impressionists. The Mediterranean environment of L’Estaque, with its abundance of sunlight and vibrant hues, captivated Cézanne. Meanwhile, Pissarro was important in convincing Cézanne to switch to a brighter palette and forsake the heavy, ponderous impasto technique in favour of smaller, more lively brushstrokes.

Cézanne returned to Paris in 1872, the year his son Paul was born. Hortense Fiquet, Cézanne’s mistress, would become Madame Cézanne in 1886, not long after the artist’s father died. Cézanne produced more than forty portraits of his partner, as well as a few cryptic pictures of their kid.

Mid Life

Cézanne developed his own methods to art as a result of his expertise with painting from nature and rigorous experimentation. Cézanne sought real and lasting visual characteristics of objects around him, rather than the representation of the fleeting instant, which had long been valued by the Impressionists. According to Cézanne, the artist must first “read” the painting’s topic via a knowledge of its core. The essence must next be “realised” on a canvas using shapes, colours, and spatial relationships in the second step.

Cézanne’s primary goal was never to depict reality as such. In his own words, he was attempting to expose “something other than reality” Cézanne painted a significant number of still lifes in the 1880s, essentially redefining the genre in two dimensions. The important shift of focus from the objects themselves to the forms and colours that were potentially transmitted by their surfaces and contours was a defining element of these still lifes.

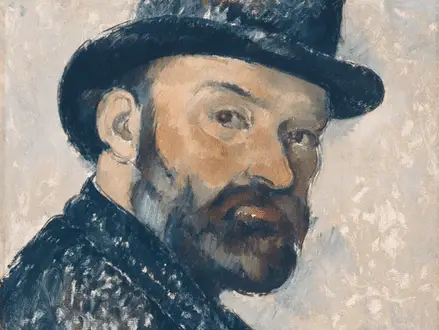

Cézanne’s portraits, including a large body of self-portraits, have a common set of characteristics. The compositions are strikingly impersonal, as Cézanne tried to represent the formal and coloristic potential of the human body and its inner nature rather than the sitter’s character.

Late Life

Cézanne’s creative endeavours were nearly entirely restricted to two visual subjects in the last decade of his life. The Mont Sainte-Victoire, a spectacular peak that dominated Aix’s dry and rocky terrain, was one example. The other was a series of so-called Bathers, which represented the ultimate union of nature and the human body (nudes depicted frolicking in a landscape). In terms of how shape and colour looked to merge together on the canvas, the Bathers’ subsequent iterations became increasingly abstract.

Paul Cézanne died on October 22, 1906, in his family’s home in Aix, after suffering pneumonia. The artist’s last decade was marked by the onset of diabetes and severe despair, both of which led to his alienation from most of his friends and family.

It’s hard to ignore the emergence of a new creative style in Cézanne’s latter work. Through painting, Cézanne provided a new way of understanding the world. In the latter years of his life, as his fame grew, a growing number of new artists were influenced by his creative vision. Among them was the young Pablo Picasso, who would soon lead the Western painting tradition in a completely new and unheard-of path. Cézanne was the first to teach a new generation of painters how to separate form from colour in their work, resulting in a unique and subjective pictorial reality rather than a slavish copy.

Famous Art by Paul Cézanne

Louis-Auguste Cézanne, the Artist’s father, Reading “L’Evenement”

1866

This portrait is one of Cézanne’s most well-known early works. Somber colours painted in a thick impasto dominate the stiff composition. The artist’s placement of his own still life in the backdrop, as if to beg acknowledgement of his talent from his famously critical parent, suggests the expressive basis for this painting. As if to press the issue, Louis-August is seen reading a liberal newspaper, which is very improbable given his conservative leanings.

The Card Players

1890-1892

Cézanne created his Card Player series of paintings, sketches, and studies in his ancestral home in the south of France, where he saw something ageless in the picture of men playing cards, similar to mountains cradling an old people. The card players appear transitory and immovable, lords of their surroundings and yet worn testaments to time’s passing, as if they gathered around a modest peasant table for a seance or cosmic discussion.

The Large Bathers

1898-1906

One of the best instances of Cézanne’s attempt to incorporate the contemporary, heroic nude in a natural environment is The Large Bathers. Under the pointed arch produced by the junction of trees and the skies, a number of extremely human nudes, no Greco-Roman nymphs or satyrs, are positioned in a variety of postures, like items of still life. The figures are devoid of individuality; the artist has assembled them only for structural considerations. Cézanne is reinterpreting a classic Western image of the female nude in this painting, but in a very radical way.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Paul Cézanne was one of the most famous Post-Impressionist French painter, and he was well-known at the end of his life for urging that painting maintain true to its material, almost sculptural beginnings.

- Cézanne, also known as the “Master of Aix” after his family birthplace in the south of France, is credited with setting the way for the aesthetic and conceptual development of twentieth-century modernism.

- In retrospect, his work is the most strong and necessary connection between Impressionism’s ephemeral elements and the more materialist creative trends of Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, and even total abstraction.

- Cézanne, dissatisfied with the Impressionist dogma that painting is essentially a reflection of visual experience, set out to create a new sort of analytical discipline out of his creative practise.

- The canvas, in his hands, becomes a screen on which the artist’s sensory impressions are recorded while he stares intently, and frequently repeatedly, at a specific topic.

- Cézanne used a sequence of distinct, systematic brushstrokes to apply his colours to the canvas, as if he were “constructing” rather than “painting” an image.

- As a result, his work adheres to a fundamental architectural principle: every part of the canvas should contribute to its overall structural integrity.

- Even a plain apple might have a sculptural depth in Cézanne’s mature paintings.

- It’s as if each still life, landscape, or portrait has been scrutinised from several perspectives, and the artist has recombined its material features as no ordinary copy, but as “a harmony parallel to nature.” as Cézanne put it.

- The future Cubists saw Cézanne as their genuine master because of this feature of his analytical, time-based approach.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.