The examination of Pablo Picasso's Cubism offers insight into the radical shifts that transformed 20th-century art and its broader cultural implications. As we explore the phases of Cubism, from its analytical beginnings to its synthetic maturity, we uncover how these artistic innovations mirrored and influenced societal changes during a tumultuous period.

Early Influences and Blue Period

Pablo Picasso's formative years were influenced by his Spanish heritage, academic training, and personal tragedies. Born in Málaga, Spain in 1881, he was son to a painter and art teacher, José Ruiz Blasco, from whom the young Picasso learned the fundamentals of formal artistic education. Spanish culture, with its rich history of visual art and tradition, shaped his approach to art from an early age.

During the late 1890s and early 1900s, Picasso's academic training under his father and later at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid provided him with a rigorous grounding in classical techniques. However, it was the real-world experiences and personal hardships that heavily influenced his most distinguished early work phase, the Blue Period from 1901 to 1904.

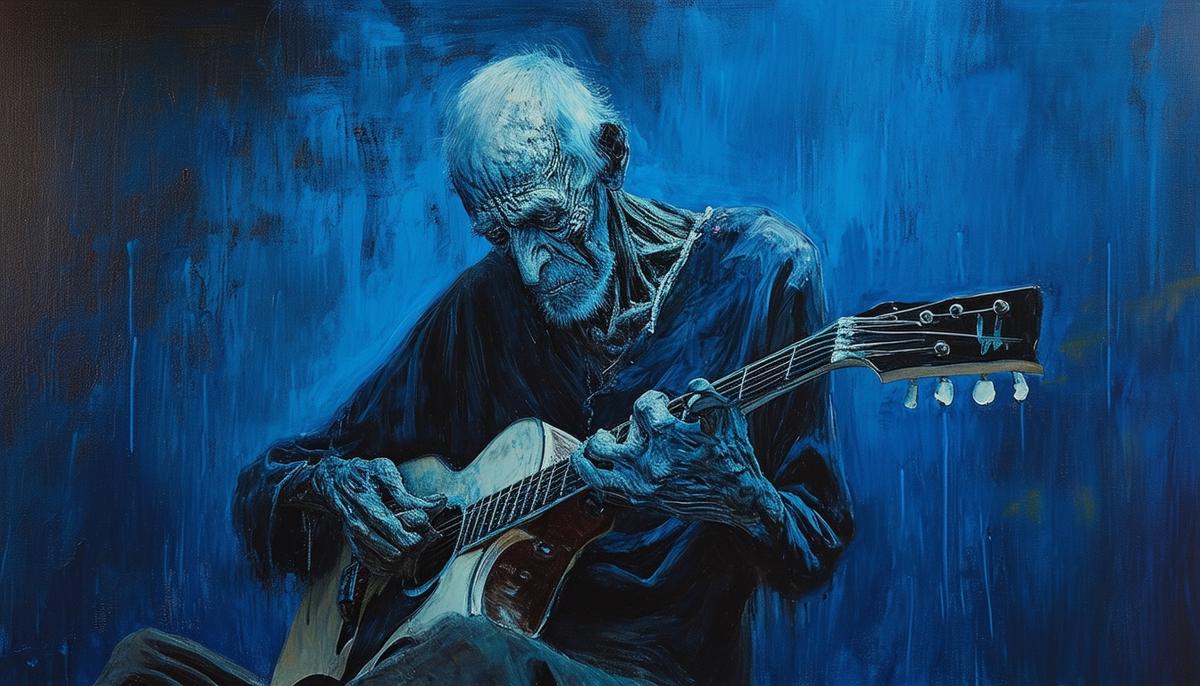

Characterised by somber monochromatic paintings in shades of blue and blue-green, Picasso's Blue Period was triggered by the suicide of his close friend Carlos Casagemas. This tragic event led Picasso to explore themes of poverty, isolation, and human misery. The melancholy and despair evident in The Old Guitarist embody his emotional state during this time—a period where he confronted near poverty, grappling with the existential angst that would inform his artistic expressions.

Amidst these personal sufferings, Picasso's exposure to the plight of the downtrodden in Barcelona's streets emerged as key influences. His engagement with symbolist ideas, particularly through his association with the Quatre Gats café circle, further pushed him towards depicting societal outcasts—beggar women and vagrants—as central subjects.

The Old Guitarist, painted in late 1903 during the peak of this phase, showcases an emaciated blind man holding onto his guitar as though it's a tangible connection to the rest of the world. The use of cool blue tones not only intersects with the symbolic sadness but concurrently sets forth the fragmented human condition, a continuing theme later evolving in his work. This piece can be seen as both a representation of solitude and an abstract portrayal of humanity's universal suffering.

The synthesis of Spanish cultural elements—intense feelings injected into portraiture combined with stark social commentary—renders his Blue Period pieces poignant examples of early 20th-century modernist art influenced by personal and cultural contexts.

Rise of Cubism

As Pablo Picasso transitioned out of his melancholic Blue Period through the more vibrant and optimistic tone of his Rose Period, his encounters with various avant-garde movements and artistic innovations propelled him toward a radical new vision that would ultimately give rise to Cubism. The turn from 1906 to 1907 marked a recalibration of his stylistic direction, prompted by his exposure to non-Western art, intensified collaborations, and theoretical evolution concerning the two-dimensional picture plane.

The defining shift toward Cubism came with one of Picasso's most revolutionary paintings, "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" (1907). This work dramatically eschewed the European artistic conventions of perspective and anatomy that had been hallmarked since the Renaissance. Its stark angularity, disjointed space, and the rigid, mask-like faces of its figures underscored a landmark departure not only in Picasso's career but in the course of Western art. Inspired by African tribal masks, which he encountered at the ethnographic museum at Palais du Trocadéro in Paris, Picasso saw an opportunity to dismantle traditional representations of the human form and space.

Picasso's collaboration with Georges Braque began an era of intense artistic dialogue and experimentation commonly referred to as the 'Cubist period.' Initially inspired by each other's inquiries into the collapsing of perspective, Picasso and Braque worked closely, navigating the uncharted terrains of the art world.

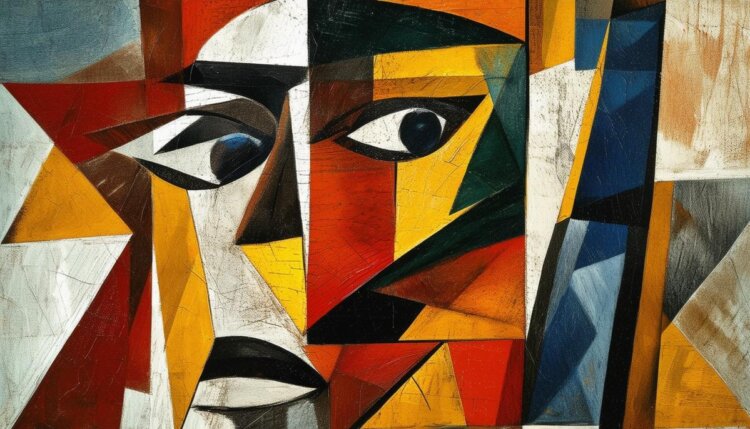

Together, they developed a visual language characterized by fragmented surfaces, interpenetrated planes, and a muted color palette that eschewed the depth and perspective inherent in realism. Through these advancements, they emphasized the flatness of the canvas while simultaneously offering a multiplicity of viewpoints—a conceptual play on how reality could be perceived and depicted. This phase, known as Analytic Cubism, pushed the boundaries of how forms could be represented, favoring structure over depth, and patterns preceding narrative content.

Cubism's radical approach reverberated throughout the art community, prompting reevaluations of form, structure, and meaning in art. It posed fundamental questions about the viewer's relationship to art:

- Should art mimic life, or could it create its own reality?

- Is a painting merely a window to the world or a world unto itself?

The Cubist revolution moved art from representational to conceptual, contributing a foundational layer to modern abstract art and establishing a bedrock for various future avant-garde movements.

These developments highlight the inherent interplay between artist and environment—a dialectic from which Cubism was born and established as a compelling account of early 20th-century modernism.

Evolution of Cubism

Initially emerging as a technical experiment, Cubism progressed into a groundbreaking art movement that radically changed perceptions of visual reality. After its genesis in the dramatic distortions of "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon," Picasso and Braque advanced towards what is now referred to as Analytic Cubism. In this initial phase, artists dissected objects into geometrical fragments and reassembled them on the flat picture plane. Colors were largely subdued—grays, blues and ochres—to keep the focus on structural mechanics rather than sensory distractions. This approach personified the Cubist intent to represent the subject from multiple angles to encapsulate the total experience of spatial reality.

The texture of paintings from the Analytic Cubism period indicates a departure from traditional artistic techniques. These compositions are cerebral orchestrations; intricate, overlapping planes suggest continuation beyond the canvas edge, making these works more about deciphering form than appreciating surface detail. The viewer is required to engage actively with the piece, participating in the process of observation—of piecing together the depicted fonts and backdrops imbued with cryptic monograms and fragmented lettering influenced by contemporary life.

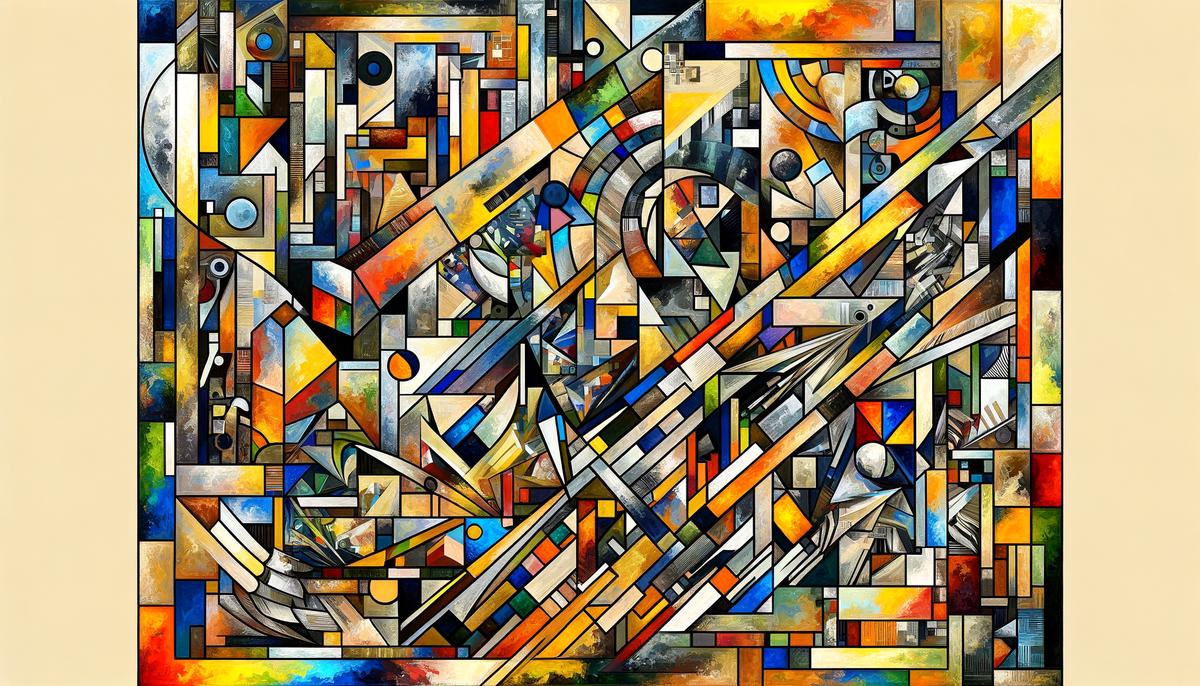

As Cubism evolved, particularly around 1912, it transitioned into what is popularly called Synthetic Cubism. This phase marks an introduction of new techniques and materials such as cut paper, sand, and even urban detritus, expanding the notion of what could be incorporated into artworks. With Synthetic Cubism, Pablo Picasso and his peers began returning to more vivid colors and greater textural contrasts, installing a sense of presence that had been conspicuously subdued in Analytic works. This phase saw the advent of collage in art—paste-ups of newspapers, wallpaper cuts, and portions of other ready-made materials onto the canvas, conflicting traditional notions of painted art as an exclusively handcrafted entity.

These innovations reflected more than an artistic urge; they were deeply entangled with the historical context surrounding them. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 meant that Cubism unfolded during a period fraught with anxiety. The incorporation of newspaper snippets and other ephemeral materials in their works may be viewed as Cubist responses to the omnipresence of media during wartime—a journalistic snapshot capturing a moment or mood through abstract scraps. This gesture bridged the ordinary experience and high art, underscoring that all facets of life were subject to the fragmentation that Cubism depicted on canvas.

By challenging the inherited prerogatives of pictorial art, the Cubists were not merely innovating in a vacuum but responding to a global cataclysm that rattled foundational norms socially, politically, and culturally across Europe and beyond. Picasso's and Braque's manipulation of form encouraged a revolution not solely in arts but also in ways viewers engaged with visual regimes of truth—an engagement that mirrored the tumultuous shifts occurring within the broader historical arena.

The duel phases of Cubism—one analytical and brooding, the other synthetic and incorporative—illustrate that each step of its evolution was as much a dialog with current events as it was with the inner philosophies seeking deeper resonance within societal transformations. Cubism emerges not just as an artistic revolution but as a mirror reflecting the complications, fractures and continual reconstructions of early 20th-century modernist society. These reflections suggest that to fully understand a period's art, we must delve into its broader historic context.

Impact and Legacy

Pablo Picasso's legacy reverberates through subsequent art movements and permeates various facets of modern culture. It is almost impossible to discuss modern art without considering the seismic shifts initiated by Picasso and his Cubist experiments. The deconstruction of form and revolutionary approach to perspective not only paved the way for later modernist styles but also transcended visual art to influence design, architecture, and even thinking in advertising and digital media.

Cubism's disintegration of form and the incorporation of multiple viewpoints encouraged later artists to push their own boundaries. For instance, Dadaists and Surrealists found in Cubism the seeds of questioning reality, using fragmented composition techniques to evoke the unconscious in dream-like arrays. Artists like Salvador Dalí wound these threads forward; the surreal layerings and curious juxtapositions in Dalí's works can trace a lineage back to such Cubist manipulation of form. Even the abstraction in American art, especially in the works of Jackson Pollock or Mark Rothko, contains echoes of Cubist spatial handling, though transposed into different narratives and scales of expression.

Cubism's introduction of non-art materials into the painting—beginning with Picasso pasting newspaper cutouts on canvas—opened avenues in art, inspiring movements such as found object art and multimedia installations. This rupture from traditional materials continues to inspire contemporary artists about notions of authenticity, resulting in works that utilize anything from urban trash to digital images, blurring lines between life and art. This challenge to traditional art paradigms initiated by Picasso continues to fuel developments in art forms such as street art and installations, where context and readiness interact dynamically with viewers' cultural landscapes.

Cubism's conceptual legacy—its abstraction and the challenge to perceptual norms—also found a place in architecture. The fragmented, diverse surfaces of Cubism inspired singular architectures where planes and perspectives are juxtaposed confusingly. Perhaps no building better suggests the metamorphosis of Picasso's innovations into architecture than the Ray and Maria Stata Center by Frank Gehry in Massachusetts, USA. The building's whimsical bends and confluences of forms echo the unpredictable convergences within Cubist paintings.

Considering impact and legacy, one must also ruminate on the millions who engage unknowingly with elements of Cubism through modern design and moving image contexts. In film, directors like Christopher Nolan have cultivated a kind of visual narrative that shifts between perspectives simultaneously—a narrative technique reminiscent of Cubist theory. The montage techniques used in movies or even the multiple frames of comic strips owe their viewpoints to Cubist fragmentation.

Picasso's Cubism reminds us fundamentally about the evolution of viewing and representation. The ever-expanding digital ethos confronts multiple perspectives every day through virtual realities and user-interface designs that espouse simultaneous visibility—a principle constituent of Cubism. Whether direct or subliminal, these multiple perspectives continue to shape how information is portrayed and products are marketed, enriching our visual language and cognitive modalities.

In contemplating these broad-ranging influences, it's clear that Cubism was never circumscribed to just the canvases it occupied. It may be seen as a launch point for a continual reconversation about our visual construct and its utility. As we value Picasso's Cubism for its formal innovations, its more profound influence lies in perpetuating a dialogue about representation—this pulsating inquiry into what seeing means across all periods of modern life.

The enduring impact of Picasso's Cubism extends far beyond the confines of the art world. It initiated a dialogue on representation that continues to influence diverse fields, challenging our perceptions and encouraging a multifaceted view of reality. This legacy of questioning and redefining visual narratives remains Picasso's most significant contribution, resonating across cultures and disciplines.

- Karmel P. Picasso and the Invention of Cubism. Yale University Press; 2003.

- Golding J. Cubism: A History and an Analysis, 1907-1914. 3rd ed. Harvard University Press; 1988.

- Green C. Cubism and Its Enemies: Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916-1928. Yale University Press; 1987.

- Rubin WS. Pablo Picasso: