Born: 1891

Died: 1976

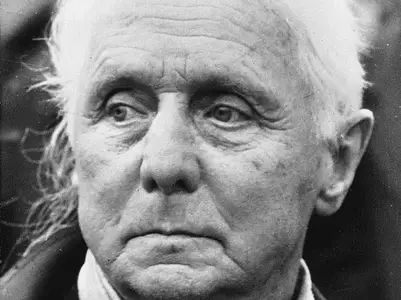

Summary of Max Ernst

Max Ernst, a provocateur, a startling and inventive artist who dug his unconscious for hallucinatory images that ridiculed societal conventions, was a German-born provocateur, a shocking and innovative artist. Ernst was a World War I veteran who emerged devastated and sceptical of western society. These tumultuous feelings flowed into his view of the modern world as illogical, a concept that became the foundation of his work. In his Dada and Surrealist works, Ernst’s creative vision, as well as his wit and vigour, are evident; Ernst was a pioneer of both genres.

Ernst spent most of his life in France and was labelled an “enemy alien” by the French government during WWII; when he came to the United States as a refugee, the US authorities used the same designation. In later life, Ernst spent much of his time playing and studying chess, which he saw as an art form, in addition to his prodigious output of paintings, sculpture, and works-on-paper. His work with the unconscious, societal criticism, and wide-ranging experimentation in topic and method have all left an indelible mark.

Max Ernst challenged painting’s norms and traditions while also holding a deep understanding of European art history. By creating non-representational works with no clear narratives, making fun of religious iconography, and devising new ways of creating artworks to convey the modern condition, he called into question the sacredness of art.

The work of the mentally ill piqued Ernst’s interest as a way to get into raw emotion and unbridled creativity.

Ernst was one of the first artists to study his own psyche using Sigmund Freud’s dream ideas in order to discover the basis of his own creativity. Ernst was delving into the general unconscious with its shared dream images while going inwards to himself.

Ernst sought to paint freely from his inner mind in an attempt to achieve a pre-verbal condition of being in order to locate the source of his own creativity. As a result, he was able to express his fundamental feelings and expose his inner traumas, which he subsequently turned into collages and paintings. This urge to paint from the subconscious, sometimes known as automatic painting, was essential to his Surrealist works and influenced the Abstract Expressionists later on.

Childhood

Max Ernst was born in Bruhl, Germany, near Cologne, to a middle-class Catholic family of nine children. Ernst learnt to paint from his deaf father, who was a severe disciplinarian and a teacher with a keen interest in academic painting. As an adult, most of Ernst’s work was to subvert authority, particularly his father’s. Ernst never got any official art training, other from this introduction to amateur painting at home, and was therefore accountable for his own creative skills. In 1914, Ernst enrolled at the University of Bonn to study philosophy, but dropped out shortly after, subsequently saying that he avoided “any studies which might degenerate into breadwinning.”

Instead, the artist selected fields of study that his instructors deemed “futile by his professors – predominately painting…seditious philosophers, and unorthodox poetry.” – primarily painting, seditious philosophers, and unconventional poetry. Ernst got fascinated by psychology and the art of the mentally ill at this period. When World War I broke out, Ernst joined the German army and fought in an artillery division, where he saw firsthand the drama and horror of trench combat on both the Eastern and Western Fronts. Ernst was one of a number of artists who returned from war duty emotionally scarred and estranged from European customs and ideals.

Early Life

Despite being mainly self-taught, Ernst was influenced by the paintings of Vincent van Gogh and August Macke, and Giorgio de Chirico’s canvases sparked his interest in dream imagery and the surreal. Ernst drew on his childhood and military experiences to create ridiculous and apocalyptic landscapes. Ernst’s rebellious streak remained strong throughout his career, since many of his works actually flipped the world upside down.

After returning to Germany after the armistice, Ernst assisted in the formation of the Dada group in Cologne, with artist-poet Jean Arp, while maintaining strong links with the Parisian avant-garde. Ernst started making collages in 1919, repurposing everyday items like scientific manuals and illustrated catalogues from the turn-of-the-century to create new beautiful, surreal pictures with no predetermined storylines. As he delved into his own mind for inspiration and to confront his own pain, Ernst used this illogical image-making to make the realm of dreams, the subconscious, and the accidental all visual.

While in Cologne, Ernst worked as a magazine editor and assisted in the staging of a Dada exhibition in a public bathroom, where guests were greeted by a charming young girl reading filthy poetry. A sculpture by Ernst was also on display, along with an axe, which the audience was encouraged to use to strike and destroy the work of art. The bourgeois sensibilities were shocked by this audience participation event.

Mid Life

Ernst divorced his first wife and relocated to Paris in 1922, where he lived and worked until 1941, when World War II made it impossible for him to stay in Europe. With the publication of André Breton’s “First Surrealist Manifesto” (191924), Surrealism displaced Dadaism throughout these decades, and Ernst became one of the movement’s original members. Ernst and his artist friends were exploring the potential of autonomism and dreams; in fact, hypnosis and hallucinogenics were used to help his creative explorations.

Ernst began experimenting with frottage (pencil rubbings of such objects as wood grain, cloth, or leaves) and decalcomania in 1925 in order to awaken the flow of imagery from his unconscious mind (the technique of transferring paint from one surface to another by pressing the two surfaces together). His experimental and technological breakthroughs resulted in completed pictures, unintentional patterns, and distinct textures, which he later incorporated into his drawings and paintings.

Late Life

Hitler and the Nazi Party had taken over Germany by 1933. Hitler had amassed about sixteen thousand items of avant-garde art from Germany’s state museums by the fall of 1937, and had sent 600 paintings to Munich for his notorious show “Degenerate Kunst” (Degenerate Art). At least two paintings by Ernst were on show in the exhibition, but they have since vanished or were most likely destroyed. After being detained three times as a German national, Ernst escaped France with the Gestapo trailing behind him.

As a refugee in New York, he ignited a generation of American painters alongside such significant European avant-garde artists as Marcel Duchamp and Piet Mondrian. Peggy Guggenheim, the colourful socialite, gallery owner, and arts lover, was to become Ernst’s third wife. Ernst had access to New York’s booming art community because to Guggenheim.

Young American artists were attracted by Ernst’s rejection of traditional painting techniques, styles, and images (as reflected by his father’s work’s classical style), as he tried to establish a fresh and unorthodox approach to painting. Ernst had a particularly great influence on Jackson Pollock’s painting, who became interested in the collage components of Ernst’s work, as well as his inclination to utilise his art as an externalisation of his inner condition. Ernst’s tremendous Surrealist experiments with autonomism and automatic writing, as well as his ability to portray the unconscious and the incidental in his paintings, piqued the curiosity of the younger artists.

After divorcing Guggenheim, Ernst and his fourth wife, American Surrealist painter Dorothea Tanning, moved to Sedona, Arizona. In 1953, Ernst and Tanning decided to return to France. Ernst won the main painting prize at the renowned Venice Biennale in 1954. A large retrospective toured America and Europe in 1971 to commemorate the artist’s 80th birthday. Ernst worked as an artist until his death in 1976 in Paris. He was laid to rest in the famous Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Max Ernst accomplished a remarkable achievement of establishing a shining reputation and critical following while still alive in three countries (Germany, France, and the United States). Despite the fact that Ernst is more recognised among art historians and scholars than among the general public, his effect on the course of mid-century American art is undeniable. Ernst associated with the Abstract Expressionists both personally and through his son, Jimmy Ernst, who became a well-known German/American Abstract Expressionist painter after the war, through his relationship with Peggy Guggenheim.

Famous Art by Max Ernst

Here Everything is Still Floating

1920

Ernst’s distinctive collage style is seen in this piece made up of unconnected cutout images of fish, anatomical drawings, insects (turned over to simulate a sailing ship), and puffs of clouds and smoke cleverly placed. Ernst established a new universe through the medium, in which randomness and illogic reflected the lunacy of WWI and called bourgeois sensibilities into question. The artist adapted these pictures from turn-of-the-century scientific manuals, ethnographic publications, and ordinary retailing catalogues.

The Fireside Angel

1937

This fanciful creature looks to be leaping with arms and legs extended and a gaudy, yet joyful, grin on its face. The creatures and their limbs have strangely coloured and deformed appendages. Furthermore, its limb appears to be producing another creature, as if it were a malignant tumour. Fireside Angel is one of the few paintings by Ernst that was directly influenced by current happenings in the globe. After Franco’s fascists beat the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, the artist was inspired to create the painting.

The King Playing with the Queen

1944

Sculpture was one of Ernst’s specialties, as seen by this notable bronze. Ernst, like fellow Dadaist Marcel Duchamp, thought of chess as a separate art form. Ernst was known for using illogical names or tongue-in-cheek puns to title his works. The oversized king (most likely Ernst himself) is shown here playing with his small queen (perhaps his wife Dorothea Tanning), who is somewhat bigger than the other pieces.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Max Ernst, a provocateur, a startling and inventive artist who dug his unconscious for hallucinatory images that ridiculed societal conventions, was a German-born provocateur, a shocking and innovative artist.

- Ernst was a World War I veteran who emerged devastated and sceptical of western society.

- These tumultuous feelings flowed into his view of the modern world as illogical, a concept that became the foundation of his work.

- In his Dada and Surrealist works, Ernst’s creative vision, as well as his wit and vigour, are evident; Ernst was a pioneer of both genres.

- Ernst spent most of his life in France and was labelled an “enemy alien” by the French government during WWII; when he came to the United States as a refugee, the US authorities used the same designation.

- In later life, Ernst spent much of his time playing and studying chess, which he saw as an art form, in addition to his prodigious output of paintings, sculpture, and works-on-paper.

- Max Ernst challenged painting’s norms and traditions while also holding a deep understanding of European art history.

- Ernst was one of the first artists to study his own psyche using Sigmund Freud’s dream ideas in order to discover the basis of his own creativity.

- Ernst was delving into the general unconscious with its shared dream images while going inwards to himself.

- Ernst sought to paint freely from his inner mind in an attempt to achieve a pre-verbal condition of being in order to locate the source of his own creativity.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.