(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1958

Died: 1990

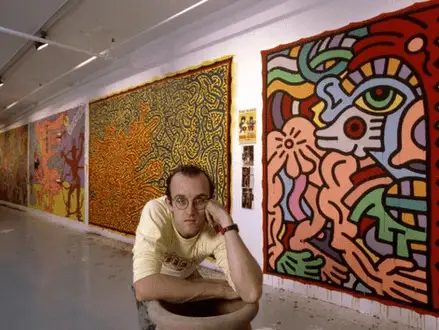

Summary of Keith Haring

Artworks by Keith Haring, like those by other artists of the twentieth century, have injected popular culture, “low art,” and non-art components into museums and galleries, when they had previously only been found in the most prestigious collections. The methods and locations he used were inspired by street art like graffiti and murals. He used bright colours and artificial pigments, and he made the artwork approachable so that spectators would be compelled to look and think, while still engaging with critical issues. Haring, along with his contemporaries Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf, helped to pave the way for the appreciation of self-taught or less-educated artists’ work that seemed basic and even cartoonish.

Drawing on the AIDS crisis, drug addiction, illicit love, and apartheid, Haring used deceptively simple images and words to make pointed cultural criticism. Artistic and activist, he demonstrated that conveying important concerns can be made amusing or at least alive by using cartoony pictures and a variety of fresh and vibrant colour schemes.

To the dismay of his colleagues, Haring’s dedication to clean lines and simple pictures resurrected figuration in painting as an alternative to the preceding generation’s more abstract and conceptual methods and the expressionistic gestural painting of his own time.

Art and political themes may be shared to a broader audience by utilising public venues that aren’t generally reserved for art. By establishing street art’s validity in fine art galleries and museums, he inspired a new generation of artists who would go from the streets to the galleries in the future.

Childhood

Haring was raised in the neighbouring town of Kutztown before moving to Reading in his early teens. His siblings were all under the age of twenty-one. His father, who created comics as a pastime, inspired him to start sketching when he was young and taught him the fundamentals. Like many other kids his age, he was a fan of Disney, Dr. Seuss, and the Looney Tunes cartoons.

Haring was reared in a United Church of Christ household and was active in the evangelical “Jesus Movement” as a kid. He now lives and works in New York City. When he was a young man, he hitchhiked across the nation, selling t-shirts he designed and created to raise money for the Grateful Dead band and to disseminate anti-Nixon sentiment.

Early Life

Once you’ve finished high school At 1976, Haring enrolled in Pittsburgh’s Ivy School of Professional Art to pursue a career in commercial art. His enthusiasm in becoming a professional graphic designer waned after just a few of semesters in school after reading Robert Henri’s The Art Spirit (1923), which begins with the sentence “Art when really understood is the province of every human being.”

He stayed in Pittsburgh for a short time and completed his studies on his own while working at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, where he saw the work of Jean Dubuffet, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Tobey. A 1977 Pierre Alechinsky exhibition and a Christo lecture, both of which urged artists to engage the public in their work, were other significant influences on his work at the time. When the original artist for the Pittsburgh Arts and Crafts Center’s inaugural solo exhibition backed out, Haring was offered the opportunity to show at the Center. His budding creative career gained confidence as a result, and he made the decision to go to New York City.

The year was 1978, and Haring had just relocated to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where he enrolled in the School of Visual Arts (SVA) while busboying at the Danceteria nightclub. He experimented in Performance, collage, Installation, and Video art while studying semiotics with conceptual artist Bill Beckley. He met fellow painters Kenny Scharf and John Sex while still in high school. He quickly learned that there was an underground alternative art culture being spearheaded by Street and Graffiti artists in the city’s streets and subways. Tseng Kwong Chi, a photographer, and fellow artist Jean-Michel Basquiat became friends.

First, Haring drew his own white chalk paintings on the subways, using the easily accessible plain black ad spots as a simple black backdrop. Here’s what he had to say about it: “The last place I saw an advertising was on the train, and it was a big, empty black screen. I knew right away that this was the ideal spot for me to do some drawing. I ascended to a card store and purchased a box of white chalk, then descended to the drawing table and drew on it. Chalk drew well on the smooth, velvety black paper.”

Riders on the New York City subway system were intrigued by the images depicting themes of life, love, sex, and death. According to Haring, “I was always astounded by how interested people were in what I had to say about them as I was performing them. No matter how old or who they were, the first thing everybody asked me was: What does that mean?” These meetings, he said, helped him focus his style decisions because of the quick and on-going feedback they provided. While refining his style of cartoon-like creatures and symbols and becoming known, he drew thousands of public drawings from 1980 to 1985. After a while, he arranged shows with other New York artists, musicians and poets at bars, restaurants, and even in unlawfully stolen buildings, known as “squats,” in the early 1980s. The Mudd Club and Club 57, in particular, were “go-to” hangouts for ambitious young creatives.

The following passage from Haring’s diary shows that even as a young man of just 20, he already had strong feelings regarding the art world. A little later, in the same diary entry, he declared the idealist axiom that “Art is life and life is art”.

Mid Life

After leaving New York’s elite art scene in 1978, Haring became known as a “rebel” street artist and alternative interior space occupant. Tony Shafrazi offered him representation, and he made his high-profile fine art debut in 1982 with a well-attended one-man show at Shafrazi’s Soho gallery. A number of important international shows followed, including Documenta 7 in Kassel, the Sao Paulo Biennial, and the New York-based Whitney Biennial.

Murals and public art projects all over the globe, including Europe, South America, and Australia, were part of his output in the 1980s. The art of ancient civilizations such as the Maya in Central America, Bahians of mixed African and native heritage in Brazil, and Australian Aborigines influenced his work for the rest of his life thanks to his travels. In 1986, he collaborated with 900 youngsters to paint a mural commemorating the 100th anniversary of the dedication of the Statue of Liberty. Following that, he painted a mural for the Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris and another for the western side of Berlin’s Berlin Wall in Germany (three years before it fell.) In addition, he earned a lot of money designing watches for Swatch and promoting Absolut Vodka. He also painted superstars like Grace Jones, the legendary 1980s singer and performer. Art like the AIDS awareness campaign and the fight against apartheid in South Africa had become politically tinged in most of his work at this point.

During this time, he became acquaintances with Andy Warhol, the famed Pop artist. This partnership, like the one with Basquiat, boosted Haring’s profile and paved the way for the elite fine art establishment to embrace his work over time. Curators in the United States were sceptical about Haring’s status as a modern artist. This gradual acceptance was reminiscent of a period in the 1950s and 1960s when forward-looking European museums purchased works by some of the most important American contemporary painters of the time before American museums in the United States were willing to embrace them. Museums in New York and Chicago like the Museum of Modern Art contain just a few of Haring’s lesser drawings, while others like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art have none whatsoever.

In 1986, Haring founded Pop Shop in midtown Manhattan, his own art retail shop. It was his idea to design the store’s interior with black and white sketches. T-shirts, toys, posters, buttons, and magnets all featured his pictures and were designed to be both popular and inexpensive. For “fine” artists like Murakami, Koons, and even Banksy, Pop Shop was a springboard for further experimentation and crossovers to mass-scale or low-cost retail products.

Late Life

In a tragic and ironic turn of events, Haring was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, at the height of his career. Throughout the 1980s, Haring utilised his artwork to push for AIDS awareness. AIDS groups received funds and artwork from the Keith Haring Foundation, which he formed in 1989 to help discover a cure for the illness. He was a busy artist for much of his life, but he passed away in 1990 at the age of 31 due to complications from AIDS.

Many people see street art as a form of protest against the established order. This includes the aristocratic realm of fine art for Haring as well. Untrained rural folk art found a role in the 1980s commercial success of Haring and others like Basquiat, but urban street art was only generally acknowledged after that time. By demonstrating that Street Art was worthy of display in fine art galleries and museums, Haring’s achievement gave Street Art credence and legitimacy. For example, Haring’s didactic, subversive, and cartoon-like art paved the way for underground cartoonist Matt Groening’s hugely successful Simpsons franchise, a satire on the modern nuclear family and American values (which included the longest-running television show in American history, among other media in which Groening’s characters and images appeared).

Murals and urban graffiti art have become so popular as art forms in the early twenty-first century that they have their own publications and websites devoted to them. In the early 1980s, successful street artists like Shepard Fairey, Banksy, and Swoon paved the path for future street-to-gallery artists like them. It was common for these artists to risk incarceration and/or censorship in order to exhibit their socially conscious work, which was sometimes shown in both public and private locations. By going against the grain, they’ve been able to negotiate better conditions for the display and remuneration of their work in the fine art world’s often more exclusive and elite circles.

Famous Art by Keith Haring

Untitled

1982

Originally painted as a child’s sketch, this glowing heart-love theme would appear in many of his later paintings and drawings. In compared to Haring’s subsequent sexually graphic works, this innocent yet divisive depiction of two guys in love seems a little light. However, Haring’s courage in depicting gay love at this time was already a huge statement and a significant cultural success. He gained confidence and the bravery to create increasingly sexually graphic depictions of homosexual people and settings as his painting career progressed. As well as Haring’s use of energy lines and the fluid movement of the individuals’ bodies in space, the above picture shows two people in love. This artwork perfectly captures Haring’s upbeat outlook on life. Haring was a romantic at heart, believing in the goodness of people and the transformative power of love.

Untitled

1984

This warped portrayal of a single gigantic masculine figure grasping his own massive, life-giving penis implies as much ambivalence as affirmation as a more vivid appreciation of the male form. As the nearly fully-grown “offspring” of the smaller figures erupt out of the phallic form, they fall perilously to the ground as the main figure’s head with its almost cubistically offset features snaps ferociously, jaws open, at the other person’s rear end. As a result, Haring’s approach to the stunning, immersive, larger-than-life outdoor mural has been carried forward into the wall-hung indoor medium of drawing on paper. Using non-male nudity and sexuality as a theme in his work, Keith Haring helped pave the way for films that tackled previously forbidden issues in both bold and subtle ways. Haring’s artwork pushed for a radical rethink of cultural possibilities as well as a widening of people’s perspective on the world.

Free South Africa

1985

Apartheid-era South Africa prompted the creation of Free South Africa as a political reaction. For ironic reasons, the black figure is purposefully bigger than the white figure. This contrast symbolises how the white minority has continued to oppress the local black people even after colonialism was over. The use of black lines gives the impression that the numbers are moving rapidly. Additionally, the use of black lines conveys a heightened awareness of more psychologically charged aspects, such as an aura around the confining collar around the black figure’s neck in the illustration.

Untitled

1985

Haring’s sculptures and collages are much less well-known. His elephant sculpture, made of papier mache and decorated with acrylics, dates from this period in his career. The white elephant was covered in several paintings of his black cartoon image. This might mean that people are taking over nature and eradicating other species as a result. Anecdotally, elephants were thought to have good memories, which means you should never forget who you were or where you came from… Because of the striking contrast between black and red, it’s possible that this black-and-white with red motif was chosen merely for its visual appeal. In contrast to this, traditionally, white has been associated with innocence whereas red has been associated with bloodshed, aggression, or passion. Although the elephant is big in scale, it is made of a material other than the normal materials used by Haring for sculpture, such as aluminium, terra cotta, or plaster. In comparison to other animals like humans, dogs, dolphins, and serpents, it’s a very unusual occurrence.

Crack is Wack

1986

Located in Harlem, New York, Crack is Wack is a large-scale public mural visible from FDR Drive. It’s a one-color orange painting with black outlines around the words and symbols. As one of a zillion mural and painting projects he worked on between 1982 and 1989, this one stands out for two reasons: first, it was created illegally, but New York rapidly accepted it, and second, because it addresses an important societal problem in an especially vulnerable location.

Rebel with Many Causes

1989

“Hear No Evil, See No Evil, Speak No Evil,” by Keith Haring is an example of Haring’s reoccurring theme: a condemnation of individuals who disregard social concerns, particularly the AIDS pandemic. Because Haring merged his identities as an artist and an activist in his work, the title alludes to his attitude as both. When it was still considered unacceptable to be openly homosexual, he dedicated his life to raising awareness about the AIDS pandemic (for example, via the campaign Respond UP) when the federal government was reluctant to act. A large number of his close friends and acquaintances perished as a result of the outbreak. In addition, he created artwork and campaigns to draw attention to topics such as overconsumption, environmental degradation, and violations of human rights, among others.

Untitled

1989

This is a very different work from what we’ve come to expect from Keith Haring. There’s a flow and elegance to his use of dynamic lines, even yet the density and maze-like pattern of the overall images on the canvas have a compulsive nature. You may observe old global symbols like Eastern Mandalas and Australian Aboriginal art, as well as current graffiti art ‘tags,’ in these works. In his work, he often employed the bright colour red (albeit in this late piece, it is slightly subdued in outlining the figures) and the new medium of paint markers to produce thick, smooth lines. Haring’s electric line compositions always had a symmetrical feel to them, allowing the viewer’s eye to follow and flow with the picture.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Artworks by Keith Haring, like those by other artists of the twentieth century, have injected popular culture, “low art,” and non-art components into museums and galleries, when they had previously only been found in the most prestigious collections.

- The methods and locations he used were inspired by street art like graffiti and murals.

- He used bright colours and artificial pigments, and he made the artwork approachable so that spectators would be compelled to look and think, while still engaging with critical issues.

- Haring, along with his contemporaries Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf, helped to pave the way for the appreciation of self-taught or less-educated artists’ work that seemed basic and even cartoonish.

- Drawing on the AIDS crisis, drug addiction, illicit love, and apartheid, Haring used deceptively simple images and words to make pointed cultural criticism.

- Artistic and activist, he demonstrated that conveying important concerns can be made amusing or at least alive by using cartoony pictures and a variety of fresh and vibrant colour schemes.

- To the dismay of his colleagues, Haring’s dedication to clean lines and simple pictures resurrected figuration in painting as an alternative to the preceding generation’s more abstract and conceptual methods and the expressionistic gestural painting of his own time.

- Art and political themes may be shared to a broader audience by utilising public venues that aren’t generally reserved for art.

- By establishing street art’s validity in fine art galleries and museums, he inspired a new generation of artists who would go from the streets to the galleries in the future.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.