(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1869

Died: 1945

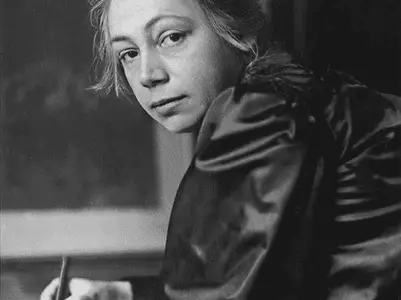

Summary of Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Kollwitz was a hard-working person who in the early decades of the 20th Century presented the conditions of workers and peasants and who gave rise to the pain and horror of both historical and contemporary fighting. Kollwitz selected against grain printing as its main medium and utilised its visual and emotional quality to provide the public an unveiled view of the underlying causes and longer-term impacts of war, based on its own socialist and anti-war convictions. While she was sometimes interested in printing and subject matter, she remained independent of them, creating her own way.

Following Goya’s prints The Disasters of War, Kollwitz’s depictions of rebellion, poverty and loss prevent a war-sacrifice melodrama in order to concentrate on distinct human experiences which are related to a broad audience. In addition to the enormous aesthetic legacy still reverberating among the graphic artists of the 20th century, her position as a famous female artist of her time guarantees her place in the annals of contemporary art.

During her artistic career as a painter, Kollwitz quickly found her true printing calling. She could reduce her graphical composition over time by mastering and experimenting with many different printing methods. She managed to eliminate foreign features and imprint them with even more emotive effects which had a more universal effect by mastering and experimenting with many different printing methods.

Rather than explore the realms of abstraction, which portray the repercussions of modernity and war, Kollwitz is dedicated to expressive realism, in order to transmit the many feelings and experiences emanating from these difficult times.

Kollwitz, as a mother and artist, was a pioneer in the development of new ways for contemporary women to express themselves beyond conventional roles in art. In a series of self-portraits, Kollwitz portrayed women working, crying and leading revolutions. During her long career, Kollwitz concentrated on parenting in all its complexity.

Known for her printing talents, Kollwitz also went into sculpture and created many monuments addressing her three-dimensional anti-war themes of loss and sorrow. The sculptures of Kollwitz, often based on religious themes such as pietà, show a profound sympathy for human suffering.

Childhood

The children of Katharina and Karl Schmidt were seven, and Käthe Ida Schmidt (later Kollwitz) was sixth. Karl studied law but declined to practise since his political views were incompatible with Prussian authoritarian regime. Subsequently he became a member of the SPD, but ultimately worked as a stonemason and a competent builder. In a close, politically and religiously conservative household, Katharina grew up. Katharina and Karl also supported the surviving four professional aspirations of their children, ensuring their daughters had access to every conceivable school and training opportunity.

Käthe, sometimes referred to by her family as “Käthushcen” (“Little Käthe”), was a timid and shy child who was prone to seizures as a kid. The scholars have attributed anxiety and psychological repression to the fits of an artist, or a condition in which one’s sensory experience is distorted to “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome” Käthe had been exposed to the eternal quiet pain of parental loss at an early age owing to her three siblings’ deaths, one of them before she was born.

Early Life

In 1881, Kollwitz started her studies in Königsberg, where she worked with Rudolf Mauer, a copper engraver. Her first career in painting was impeded by her failure to work with colour at the Women’s School of Art in Munich as well as other official academic courses. After reading the 1885 booklet Malerie and Zeichnung, the artist realised that she was “not a painter at all,” but a printer (Painting and Drawing).

After a seven-year engagement, Kollwitz married the ardent communist and orphan Dr. Karl Kollwitz whom she knew years before while studying with Mauer. Karl began working as a doctor in Berlin, where he sought to provide social and medical insurance for employees. The nearness of her studio to Karl’s medical company in the big city inspired her early interest in painting women and children from the working class who came as patients to visit their husbands. By the turn of the century, ladies of the working class had become her favourite subject.

It was not easy for Kollwitz to marry and risk losing her creative freedom, and the response she received from both her own family and other female artists was made more difficult. Her father was afraid that marriage would jeopardise her artistic potential and thus, by sending her to many art schools, he tried to keep Kollwitz und Karl apart. This parental worry shared with Kollwitz’s fellow students at Munich Woman’s School of Art, spoiling him for choosing a route they regarded as a certain death knell for an artistic career.

Hans, the first son of the artist, was born in 1892 and Peter, the second son of the artist, was born in 1896. The Kollwitz children would become significant themes in their work later. Karl Kollwitz was a dedicated husband and dad despite the challenges of the maternity of the 19th century, who with the family housekeeper made sure that Kollwitz had time to focus on his work. Later in life, Kollwitz recognised her unique position as a lucky woman both as an engaged artist and a loving mother and she helped one of her fellow students from Munich who, unable to handle the combined weight, lived in poverty in Paris. Kollwitz adopted the eleven-year-old son of this classmate in 1904.

In 1893 Kollwitz took part in the premiere of Die Weber (The Weavers), the poet Gerhart Hauptmann’s play, which marked a turning point in her career. The play portrayed the revolt of the farming weavers in 1844 in which the weavers protested their low wages and terrible living conditions. Due to its background, personal values and political commitment, Kollwitz was inspired by the storey. She would later use this performance as a “milestone in my work,” leading her to forgive all her previous creative efforts and to fully translate Hauptmann’s work into the six-plate print series The Weavers (1897).

According to Martha Kearns, the Weavers “transformed” Kollwitz into a “an artist who celebrated revolution.” Kollwitz devoted her first print series to her father and was won the National Gold Medal when it was exhibited in Dresden in 1899. “from then on, at one blow, I was counted among the foremost artists of the country.” Later, Kollwitz would remark on the award. In the late 19th century, Kollwitz became the only female artist in Berlin’s avant-garde organisation Secession Die Sezession, and in 1909 she started her sculpted career with a memorial bust of Julius Rupp, her maternal grandfather.

Mid Life

The mature period of Kollwitz was dominated by art in support of her developing socialist convictions and the artist produced prints exposing the realities of poverty or exploitation in Berlin. Women became a core subject of her work and she printed and postered women revolutionary heroes who led the path to social change as well as the strength, difficulties and perseverance of working-class mothers facing the greatest difficulty. Her political actions went beyond her themes, making printing simple to duplicate and affordable for her prints, which guaranteed that her work was broadly accessible.

During the first WWI, Kollwitz worked as a cook and assistant in a cafeteria serving the jobless as well as poor women and their children. In Belgium soon after the war started, her son, Peter, was killed in battle and Kollwitz became a pacifist. Although she has been a devoted socialist throughout her life, Kollwitz never joined any of the progressive political organisations, and in the words of biographer Martha Kearns, she was not “a political person in the orthodox sense.”

During the First World War, Kollwitz’s work became linked to the Expressionist movement. At that time both forms of German expressionism, Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, had been officially dissolved; nevertheless, the cultural links of the expressionist movement had moved to leftist artists painting in a non-realist manner. Although Kollwitz was not a member of any Expressionist body and frequently criticised the art of artists labelled as “Expressionist” who dismissed their works as “pure studio art” the expressionist term was acceptable to her.

After the printer and artist Ernst Barlach’s work at the Berlin New Secession exhibition, Kollwitz started her lengthy exploration with woodcuts in 1920. The artist was searching for an alternate printing for grafting, which she found difficult to handle due her lack of eyesight and lithography was a tough method for printing a nice, exact image. The artist extended her work to include, in addition to woodcuts, sculptural works.

Late Life

As Germany’s most successful female artist, Kollwitz’s fame peaked towards the conclusion of the Weimar period. She had to use a typewriter to maintain her increasing mail since she was well-known (though she herself made a point to personally answer every letter).

With the rise of national socialism, the anti-war and leftist political inclinations of the artist and her non-naturalist aesthetic attracted Nazi attention. In 1932, after finally recognising her homage to her dead son Peter, she was concerned about putting the sculptures of the memory in the fear that the Nazis would “deface them with swastikas.”

The NSIs threatened to dissolve the Prussian Academy unless the Prussian Academy resigned from office in 1933 and Kollwitz and her colleague, who had both signed a petition seeking to unify the Left before the elections. The oppressive and retrogressive circumstances of the Nazi government also affected its artistic importance, and its work was prohibited. However, after the rise of Hitler, the political right moved away from the work of Kollwitz, and the KPD decided that its work was “too pessimistic” according to Vries, because it “failed to lift the workers out of their plight, and instead focused on their misery.”

Although Kollwitz was rejected by both the left and the right, she kept producing sculpture, even though she thought her subsequent pieces were ultimately useless because “everything has been said before.” In 1936, the Gestapo began a year of campaign against Kollwitz and, unless it renounces its anti-Nazi sentiments and cooperates, it threatened to transfer them to a concentration camp. The threat was never brought about, perhaps due to the support and protection she received as a respected part of her society, but from then on both Käthe and Karl kept a vial of poison with them if caught by the Nazi.

The practise of Karl was banned in 1938 and Käthe and Karl sank into misery. Kollwitz was given refuge by a collector in America, but she refused to remain with her family. Meanwhile, since their photos were well-known and emotionally accessible, the Nazis seized their activist prints, such as Brot!, for propaganda by themselves.

During the Second World War, Karl Kollwitz died in 1940 and her grandson Peter Kollwitz perished in Russia.

Kollwitz fled her home in Berlin in 1943, and bombs soon destroyed it.

In 1944 she was forced to leave her fortune-telling rooms again, this time from the estate of collector Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony, Mortizburg. In june 1944, Depressed by the endless devastation and human burdens of the war, Kollwitz asked her son Hans for his permission to commit suicide; he encouraged that she wait until the war is over, with a sense of responsibility as a leading role model at least until the conclusion of the war. On 22 April 1945, at the age of 78, Käthe Kollwitz died of heart failure.

Kollwitz was critical in the interwar years to increase women artists’ visibility and professional validity. She was initially recognised as the female judge of the new secession in Berlin in 1916, and first accepted to the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1919. (though she refused to use the title of “professor”). In 1926 she helped establish the Society for Women Artists and Freunds of Art and in 1928 became the first female department head of the Prussian Academy of Arts. During her lifetime, the art of Kollwitz has been recognised worldwide. She visited the Soviet Union in 1927 to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Communist State.

Famous Art by Käthe Kollwitz

Misery (Not)

1897

The Weavers’ Insurrection, Kollwitz’s artistic reaction to Gerhart Hauptmann’s drama about the 1844 German weavers’ rebellion, is an intimate representation of the artist’s respect and passion for the working classes. The series is notable for depicting working-class people “initiat[ing], execut[ing], and suffer[ing] the fate of their own uprising” and for portraying women as active participants in a violent clash, according to biographer Martha Kearns. In a critical departure from Hauptmann’s drama, Kollwitz opened her series with Misery, a scene depicting a child’s death as a result of poverty.

The Mothers (Mütter)

1919

While The Mothers was not included in the final series War, it was produced when Kollwitz sought to transition from woodcuts to lithographs for the series. A self-portrait of Kollwitz as a mother, holding her sons Hans and Peter as young children, dominates the foreground of this lithograph, which she produced on the birthday of her deceased son Peter.

From her early social justice images through her studies of war, sorrow, and the less apparent effects of warfare, the artist’s work was dominated by the topic of mothers. Kollwitz depicted the dilemma and psychological toll that sons enrolling or being recruited into the military impose on the moms they leave behind.

Seed for the Planting Must Not be Ground

1942

“Seeds for Planting Must Not Be Ground.” a line from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, inspired Kollwitz’s final print, which she considered as her “last Will and Testament” and created fast. The piece expresses the artist’s dissatisfaction with the fact that the globe was once again engulfed in a conflict with an incalculable and needless human cost. The artist takes Goethe’s statement to mean that children’s lives should not be cut short because of the futility of war.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Käthe Kollwitz was a hard-working person who in the early decades of the 20th Century presented the conditions of workers and peasants and who gave rise to the pain and horror of both historical and contemporary fighting.

- Kollwitz selected against grain printing as its main medium and utilised its visual and emotional quality to provide the public an unveiled view of the underlying causes and longer-term impacts of war, based on its own socialist and anti-war convictions.

- While she was sometimes interested in printing and subject matter, she remained independent of them, creating her own way.Following Goya’s prints The Disasters of War, Kollwitz’s depictions of rebellion, poverty and loss prevent a war-sacrifice melodrama in order to concentrate on distinct human experiences which are related to a broad audience.

- In addition to the enormous aesthetic legacy still reverberating among the graphic artists of the 20th century, her position as a famous female artist of her time guarantees her place in the annals of contemporary art.During her artistic career as a painter, Kollwitz quickly found her true printing calling.

- She could reduce her graphical composition over time by mastering and experimenting with many different printing methods.

- She managed to eliminate foreign features and imprint them with even more emotive effects which had a more universal effect by mastering and experimenting with many different printing methods.Rather than explore the realms of abstraction, which portray the repercussions of modernity and war, Kollwitz is dedicated to expressive realism, in order to transmit the many feelings and experiences emanating from these difficult times.Kollwitz, as a mother and artist, was a pioneer in the development of new ways for contemporary women to express themselves beyond conventional roles in art.

- In a series of self-portraits, Kollwitz portrayed women working, crying and leading revolutions.

- During her long career, Kollwitz concentrated on parenting in all its complexity.Known for her printing talents, Kollwitz also went into sculpture and created many monuments addressing her three-dimensional anti-war themes of loss and sorrow.

- The sculptures of Kollwitz, often based on religious themes such as pietà, show a profound sympathy for human suffering.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.