(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

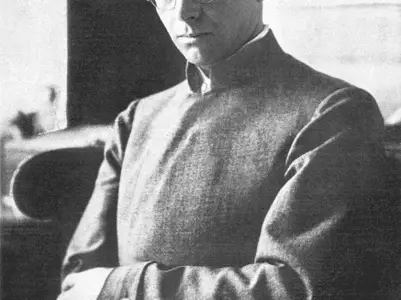

Born: 1888

Died: 1967

Summary of Johannes Itten

Itten began his career at the Bauhaus as a teacher, and he served as a Master there from 1919 to 1923 after receiving his teacher’s training. His introduction of the school’s first-year art class marked a watershed moment in the history of art education. To avoid copying works of the Old Masters, he urged students to explore their own feelings and experiment with colours, materials and shapes.

The focus of this workshop was on studying natural forms and colours, analysing classic works of art, and drawing from life. While serving as a top administrator at some of the world’s most prestigious art schools, he pioneered comprehensive art education and founded his own art school.

Bauhaus teacher Itten pioneered practises that are still essential in today’s art education, such as encouraging students to express themselves and to experiment with new materials and processes. Prior to enrolling in more specialised courses, all Bauhaus students were expected to take this course as their foundation.

The Eastern Mazdaznan adherent Itten pushed his students to incorporate mysticism into their artistic endeavours. With the use of breathing exercises and gymnastic routines, he taught students how to cultivate their creative potential. There were many who followed his teachings at the Bauhaus before the school’s shift to an industrial mentality forced him to leave.

An complex colour theory devised by Itten was related with different types of individuals and seasons. Color contrasts, characterised by seven various sorts of comparisons, were critical to the development of Op Art, but also influenced the palettes of cosmetic corporations in the late twentieth century.

Famous Art by Johannes Itten

The Encounter

1916

There are many of the essential ideas that Itten would teach at the Bauhaus in this colour abstraction, despite the fact that it was painted before he arrived there. As a child, he was fascinated with geometric shapes, such as the recurring spiral, and he also experimented with the colour spectrum.

Encounter, despite being non-objective, is laden with personal and symbolic significance. Hildegard Wendland, Itten’s girlfriend, committed suicide in 1915, and a string of paintings with similar compositions and palettes were made around the same time. Two intertwined spiral patterns dominate this piece, which is also known as Meeting. As a Theosophical archetype of geometric forms in nature and a symbol of transcendence beyond the physical, concrete world, this specific shape has a wider universal significance.

The artwork can also be viewed as a study in dynamic colour contrasts, which were achieved using a wide spectrum of hues in the painting. Gradations of vivid colours, from yellow to blue, can be seen in the horizontal stripe on the lower right. The dominating form of the double helix is overlaid on top of vertical metallic stripes, creating a rhythm of dark and light. The spiral is divided in half, with one half listing colours and the other half listing grey values, until they meet in the middle at a grey and pastel yellow intersection. The end effect resembles a kaleidoscope of cosmic hues arranged in a harmonious geometric pattern. Although Itten drew from Kandinsky’s impact, he also influenced other Bauhaus students and instructors including Paul Klee, Josef Albers, and Hans Hofmann.

Study of Contrasts (reconstruction of student project)

Artist: Moses Mirkin

1920

Itten’s Vorkurs first-year students created this piece as part of their study in material experimentation and contrast and form. An important shift from the norm in art education, which stressed copying from casts and prints, occurred here. Itten, an elementary school teacher by training, was heavily influenced by Friedrich Froebel’s philosophy, which held that children learn best via play.

Many of Itten’s design challenges were centred on the investigation of everyday materials. His pupils had the luxury of a few days to create their designs. To come up with innovative solutions, they were compelled to work intuitively in response to the materials. Instead of assigning grades based on individual attempts, which Itten believed would inhibit students’ creativity, he would speak to the class about common mistakes and let them vote on the best work. Open-ended experimentation, group discussion and individual expression have become a fundamental part of the art education concept.

This sculpture was characterised as follows in the 1923 Bauhaus catalogue: “material and expressive form contrast (jagged-smooth); rhythmical contrast. Combined contrast effect. Use a variety of forms of expression at the same time to compare how different people express themselves.” To encourage pupils to uncover the “fundamental and conflicting” aspects of various materials, Itten’s lessons were frequently organised around such contrasts. The Bauhaus curriculum was arranged by medium, and this emphasis on materiality would guide pupils as they progressed beyond this first lesson.

Tower of Fire

1920

A trained architect, Walter Gropius was the Bauhaus’s creator and the school’s ultimate purpose was to use architecture to unite all other forms of media. The majority of Itten’s architectural designs were based on dynamic groupings of elementary geometric forms when he was at the school. In fact, this architectural sculpture served as a model for a public monument that was never built. Itten’s journals describe the proposed project as a beacon for the Weimar airport, based on the descriptions. At the Bauhaus, a model of Itten’s studio was put outside of the building.

Yellow, blue, and red leaded glass projections repeat throughout the tower as it climbs around its centre core. Stacks of cubes were intended to be made from three distinct materials: clay or stone for the bottom four, metal for the middle four, and fire for the top four, representing the four basic elements of earth, water, air, and fire, according to Itten’s notes. Itten’s colour theories and modern musical tonal explorations, as well as the traditional and zodiacal calendars, all contributed to the numerological significance of the number 12. Ascending, concentric, conic structures having symbolic significance, borrowed from Theosophy and mystical geometries, surround these cubes. Transcendence was achieved through a spiral, which rose above the material world in order to reach a higher consciousness. As a primitive form that recurs throughout nature, it suggests that utopian ideals from the distant past and the near future are interconnected.

Bruno Taut’s glass architecture and Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International are also examples of utopian ideas from the early 20th century that are similar to Itten’s Tower. Despite his opposition to Bauhaus’s expanding industrialisation, Itten uses these contemporary materials to create a structure that is both expressive and organic in this work of art.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.