Born: 1780

Died: 1867

Summary of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres reinterpreted Classical and Renaissance materials for 19th century sensibilities with a bold combination of conventional technique and experimental sensuality. He was at the centre of a revived version of the ancient debate: is line or colour the most important element of painting? A talented draughtsman known for his serpentine line and impeccably rendered, illusionistic textures, he was at the centre of a revived version of the ancient debate: is line or colour the most important element of painting? However, Ingres was not always successful; early in in his career, his attempts with abstracting the body and introducing more exotic and emotionally complicated topics were met with harsh criticism. In reality, his work may best be described as a mix of Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

Ingres, one of Jacques Louis David’s most gifted students, had early success, winning the prestigious Prix de Rome on only his second try. While Ingres’ paintings always reflected David’s classical style, he tainted his master’s legacy by distorting his figures and adopting storylines that contradicted his teacher’s moral exemplars.

Ingres extended the abstraction of the body beyond Neoclassical idealism in search of more attractive shapes and harmonious line. To emphasise elegant curves and a pleasing visual impact, he abstracted his figures, even departing from the realistic structure of the body. From Renoir (who was reputedly smitten with Ingres) through the Surrealists of the twentieth century, this new degree of freedom would drive other painters to experiment with the human figure.

Despite his breaches, Ingres was unmistakably linked to the classical heritage and academic style as compared to the Romantics’ painterly brushwork and bright palettes, such as Eugène Delacroix. He came to symbolise the Poussinistes in the mid-nineteenth century, who felt that the intellectual quality of the drawn line was more important to a painting than the emotional effect of colour, as opposed to the Rubenistes, who preferred the emotional impact of colour. Ingres adapted Renaissance ideas for the contemporary period as a protector of tradition, working in particular following the model of Raphael.

Childhood

Jean-Auguste-Dominique was born in 1780 in Montauban, a tiny town in southern France, to the sculptor, painter, and musician Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres. He exhibited an early knack for violin and a penchant for sketching under his father’s instruction; his earliest-known signed drawing is from 1789. When the Collège des Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes in Paris collapsed during the French Revolution, his schooling was cut short. Ingres’ father sent him to the Académie Royale de Peinture, Sculpture et Architecture in Toulouse in 1791, where he studied under painters Guillaume-Joseph Roques and Jean Briant, as well as sculptor Jean-Pierre Vigan.

From 1794 until 1796, he pursued his passion in music by playing second violin with the Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse. The phrase “Ingres’s violin,” was used to denote a tremendous but secondary skill that was obscured by one’s major employment; the term would subsequently serve as the title for a famous Surrealist image by Man Ray in 1924.

Early Life

Ingres left Toulouse for Paris in August 1797, following the traditional path of ambitious young painters; his father having secured him a seat in the workshop of the famous Neoclassical master, Jacques-Louis David. He would gain not just from David’s instruction, but also from the dynamic Parisian art scene. Recent French military triumphs in Holland, Belgium, and Italy had delivered prizes from historical art collections to Paris, giving Ingres unparalleled access to Renaissance masterpieces.

As a student of David, he developed strong bonds with his classmates, particularly Étienne Delécluze, subsequently one of Neoclassicism’s most ardent opponents and supporters; he also befriended notable former pupils like as Anne-Louis Girodet and Antoine-Jean Gros. This “School of David,” followed many of their master’s teachings, but also went against his example, favouring more emotionally evocative and sensual topics, which promoted a less rigorous manner of painting. According to Delécluze, Ingres preferred to work alone, focusing only on the development of his own particular style.

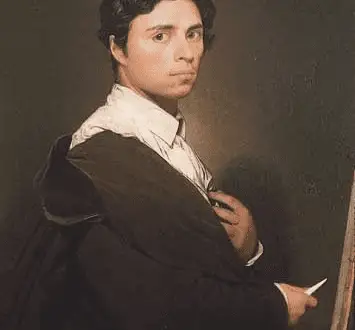

Ingres’ early work displays both his grasp of academic norm and his experimental departures from it; this combination gained him early recognition, with his Ambassadors of Agamemnon (1801) receiving the Prix de Rome. Political unrest and financial constraints forced him to postpone his trip to Rome for five years. Ingres continued to paint in Paris during this time, swiftly proving his ability for portraiture. He entered five portraits in the Salon of 1806, including an early self-portrait, portraits of the Rivière family, and, most famously, Napoléon I on his Imperial Throne (1806).

Mid Life

Ingres was expected to submit work to Paris to demonstrate his development as the winner of the Prix de Rome; he was motivated to succeed in his contributions. Instead of just returning a naked academic man, his Oedipus and the Sphinx (1808) turned the exercise into a historical painting, the Academy’s favourite genre. Ingres also purposefully developed ties with wealthy clients, obtaining contracts for both history paintings and portraits through his connections at the Académie.

While he considered portraiture to be a minor use of his abilities, his 1813 marriage to Madeleine Chapelle made it profitable and necessary. Ingres only survived the Napoleonic Wars’ financial repercussions, which culminated in the Empire’s downfall in 1814, because of his reputation as a portrait painter. While the state’s acquisition of his Roger Freeing Angelica from the Salon in 1819 encouraged him, his other works were not as well appreciated, so he stayed in Italy, relocating to Florence in 1820.

Ingres earned his most important commission of his career just weeks after arriving in Florence. To commemorate Louis XIII’s dedication of France to the Virgin Mary in 1638, the French ministry of the interior ordered a large-scale religious painting for the cathedral in Montauban, the artist’s homeland. The result was The Vow of Louis XIII, which was completed in 1824 and was a resounding success at that year’s Salon.

Ingres became the primary defender of the classical heritage in contrast to the emerging tendency of Romanticism (represented at the same Salon by Eugène Delacroix’s Scenes from the Massacres at Scio). This was a watershed moment in his career. Ingres’ triumph at the Salon, as well as his election as a corresponding member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1823, allowed him to return to Paris in 1824 as a success after 18 years away. The next year, he was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor by Charles X, as well as a contract for The Apotheosis of Homer, a great historical painting on a ceiling at the Louvre (1827).

Despite his formal acknowledgment, Ingres had a few missteps. The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian, created in 1834 for the church in Autun, earned mixed reviews at that year’s Salon; reviewers panned the painting’s gloomy tonalities, chaotic arrangement, and anatomical deformation of his figures. Ingres swore he would never exhibit at the Salon or accept government contracts again, despite his volatile reputation. He closed his Parisian studio and applied for the directorship of the Académie de France in Rome. In December 1834, he returned to Rome after narrowly defeating fellow painter Horace Vernet by one vote.

Late Life

Despite his dramatic departure from Paris, Ingres was not fully truthful to his promise. Antiochus and Stratonice (1840), commissioned by Prince Ferdinand-Philippe, a renowned collector and son of King Louis-Philippe, was warmly received at a private exhibition held at the patron’s home. Following this triumph, Ingres returned to Paris in 1841 following a six-year stint as director of the Académie in Rome, saying to a friend, “I’ve been proven right. Despite the fact that I have always been a timid and meek little kid before the Ancients, I must say it is quite pleasant to see tears flowing in from my works, especially from people with excellent and refined senses”

Ingres decided to participate in an 1846 retrospective showcasing Jacques-Louis David and his most formidable students, despite vowing never to exhibit his work in public again. Ingres had a high position; he had the most works on exhibit after his teacher, and reviewers praised his portraits, calling him “our century’s master without equal with regard to his portraits.” Then, in 1855, during the Exposition Universelle, he was celebrated with a monographic retrospective and a gallery dedicated just to him. Despite this show of appreciation, Ingres was enraged that he would have to share the grand medal of honour with nine other painters that year.

In his book Keeping an Eye Open, author and art critic Julian Barnes highlights a particularly fascinating event in the rivalry between Ingres and Delacroix (2015). “[The 19th-century writer Maxime] Du Champ tells the storey of a banker who, oblivious to artistic politics, managed to invite both painters to dinner on the same evening by accident.” Ingres could no longer contain himself after much scowling. With a cup of coffee in hand, he approached his opponent with a mantelpice. ‘Sir! Drawing implies honesty!’ he said. ‘Drawing signifies honour!’

Ingres’ profession grew increasingly private in the latter decade of his life, as he concentrated on creating works for his intimate friends and family. He was adored, and Emperor Napoléon III even made him a Senator in May 1862, but his later years were spent revisiting old subjects and long-forgotten paintings, such as reworked renditions of Homer’s Apotheosis, Antiochus and Stratonice, and Oedipus and the Sphinx. His final piece, “a large Virgin with the Host and two angels,” is dated December 31, 1866, and is documented in a journal as “a large Virgin with the Host and two angels.” Ingres would succumb to pneumonia within two weeks. He left the furnishings of his studio to (what would eventually become) Montauban’s Musée Ingres.

Famous Art by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Napoléon on his Imperial Throne

1806

Ingres’ picture, which is today considered the most famous portrait of Emperor Napoléon I, was first rejected as excessively gothic, antiquated, and even “barbaric.” The freshly crowned emperor is lavishly decorated and shown within a jumble of Roman, Byzantine, and Carolingian emblems. The oddity of his intimidating frontality, which rises from layers of ostentatiously royal clothing to glare beyond the observer with a steely gaze, overshadows the effort to legitimate his claim to power.

La Grande Odalisque

1814

Ingres’ rendition of the female nude, which has a long history, displays both his intellectual knowledge and his proclivity for experimentation. Indeed, images of the idealised nude may be traced back to ancient Greek depictions of Aphrodite. Since the Renaissance, the reclining lady had been a popular theme; Titian’s Venus of Urbino was undoubtedly an important example for Ingres. Ingres maintains this tradition by depicting the lady in a rich environment decorated with glossy textiles and beautifully detailed jewels, as well as by sketching her in a succession of sinuous lines that highlight the delicate contours of her body.

La Fornarina

1814

La Fornarina was originally intended as part of a sequence of paintings portraying the life of Ingres’ idol, Raphael, and depicts him in the arms of his supposed mistress. Despite abandoning the assignment, Ingres painted five or six variations of this subject. It gave him the opportunity to express his admiration for Raphael while also demonstrating his mastery of the precise and illusionistic technique.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres reinterpreted Classical and Renaissance materials for 19th century sensibilities with a bold combination of conventional technique and experimental sensuality.

- He was at the centre of a revived version of the ancient debate: is line or colour the most important element of painting?

- A talented draughtsman known for his serpentine line and impeccably rendered, illusionistic textures, he was at the centre of a revived version of the ancient debate: is line or colour the most important element of painting?

- However, Ingres was not always successful; early in in his career, his attempts with abstracting the body and introducing more exotic and emotionally complicated topics were met with harsh criticism.

- In reality, his work may best be described as a mix of Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

- Ingres, one of Jacques Louis David’s most gifted students, had early success, winning the prestigious Prix de Rome on only his second try.

- While Ingres’ paintings always reflected David’s classical style, he tainted his master’s legacy by distorting his figures and adopting storylines that contradicted his teacher’s moral exemplars.

- Ingres extended the abstraction of the body beyond Neoclassical idealism in search of more attractive shapes and harmonious line.

- He came to symbolise the Poussinistes in the mid-nineteenth century, who felt that the intellectual quality of the drawn line was more important to a painting than the emotional effect of colour, as opposed to the Rubenistes, who preferred the emotional impact of colour.

- Ingres adapted Renaissance ideas for the contemporary period as a protector of tradition, working in particular following the model of Raphael.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.