(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1748

Died: 1825

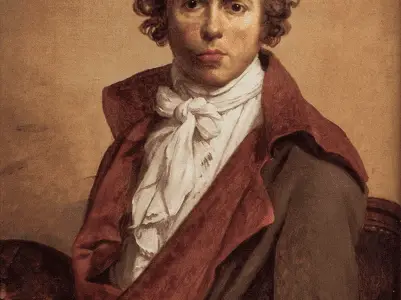

Summary of Jacques-Louis David

The archetypal Neoclassical painter, David’s enormous paintings were possibly the crowning triumph of conventional historical painting. David combined antique topics with Enlightenment thought to produce moral exemplars in the popular Greco-Roman style. His linear shapes vividly depicted storylines that frequently paralleled current events. Despite the fundamental contrasts in these ruling regimes, David served the monarchy of Louis XVI, the post-revolutionary administration, and Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte as the preeminent painter of his time. He also operated a prestigious studio, where his students would eventually revolt against his leadership, planting the roots of modernism.

David was the first French artist to combine classical topics with minimalist composition and linear accuracy. His paintings, which completely rejected the Rococo’s ornamental and artistic qualities, generated strong, didactic works of moral clarity with minimal distractions or visual embellishments. David’s paintings were created in response to a need for art that clearly communicated civic ideals to a broad audience.

Although works like The Oath of the Horatii and The Death of Socrates were linked with the Revolution of 1789, David’s early triumphs were iconic pictures of heroism and heroic acts, commissioned by royal and aristocratic clients who embraced the classical style as the newest fashion. David, a political chameleon, modified this Neoclassical style to stay effective during the turbulent late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. The monarchy, the Revolutionary administration, and Napoleon Bonaparte all utilised David’s classicism to support their claims to power.

Although David is most known for his work during the French Revolution, when he sat on the National Council and coordinated propaganda, he was also a skilled politician who tailored his art to the requirements of each of his patrons. This skill set a precedent for engaging with modern issues and adapting to various political activities.

The Academy taught sketching; students would apprentice in a master’s studio to learn to paint. David’s studio became the most significant training environment for late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century artists. Although many of his students would later rebel against this model and turn to the burgeoning Romantic movement and its spiritual questioning, his legacy was cemented by generations of artists who could trace their training back to David’s studio – his most famous student being Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Childhood

Following the murder of his merchant father in a gun fight when the future artist was just nine years old, Jacques-Louis David was reared by his mother’s two architect brothers and schooled at boarding school. David rejected his family’s expectations that he would study architecture, law, or medicine and instead choose to be an artist.

Early Life

David’s cousin, the famed Rococo artist François Boucher, arranged for the young artist to study with the more fashionable artist Joseph-Marie Vien, feeling that their styles were complementary. David was injured as a student during a fencing competition with a classmate, suffering a face injury that exacerbated a speech impairment. The wound later turned into a non-cancerous tumour, which made his speaking much more difficult and resulted in a noticeable facial deformity.

He began his studies at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1766. He was determined to win the prestigious Prix de Rome (which provided funding for a residency in Rome), but he was initially unsuccessful. David, not a gracious loser, tried to starve himself to death after losing one try and publicly despised the artist who won the award, Joseph-Benoît Suvée, subsequently calling him “ignorant and horrible.” He developed a phobia that lasted the rest of his career because he believed the judges were biassed against him.

David’s first commission, an altarpiece, St Roch Interceding with the Virgin for the Plaque Stricken (1780), came while he was in Rome, and it gained him considerable fame. He turned down a scholarship to stay at Rome for another year, realising that his reputation had been established, and returned to Paris to begin his career.

Mid Life

David was well-known in Paris for his work and his outspoken, often controversial conduct, which frequently clashed with the French Royal Academy. Despite his arrogance and refusal to follow appropriate protocols for presenting his paintings, his meticulous execution and highly dramatic storylines elevated him to the forefront of the new classicizing style.

This was a response to criticism of the Rococo in the mid-nineteenth century, which catered to aristocratic tastes with colourful, often immoral, leisure works. Denis Diderot has been a vocal advocate for redefining art as an educational tool for instilling correct civic qualities in a broad audience. The Death of Socrates by David, then in Paris as the American envoy to France, drew the attention of future American president Thomas Jefferson, who remarked after witnessing the Salon of 1787, “The best thing is the Death of Socrates by David, and a superb one it is.”

The riches of David’s wife Suzanne, with whom he would have four children, as well as the money he got for portraits of affluent and important French families and royal commissions, helped sustain their family. David took on numerous students as a member of the Academy, having one of the most prominent painting studios where new painters could apprentice. This “School of David” would produce the next generation of French painters, despite the fact that many of them would reject their teacher’s approach. When a pupil gained too much attention or David felt they were endangering his own creative status, David was not beyond petty jealousy.

While The Oath of the Horatii (1784), which became a visual emblem of the people’s fight, was created for a royal patron years earlier, David is typically connected with the French Revolution of 1789. He eventually became a full-fledged Revolutionary War combatant, associating himself with the extreme Jacobin faction. He supervised the deaths of erstwhile friends who opposed Revolutionary principles as a member of the National Convention. He even voted in support of Louis XVI’s death, which caused his wife to leave him.

He also utilised his work to promote and celebrate the Revolution and its heroes, including Jean-Paul Marat, the most renowned of whom. His memorial artwork depicting Marat’s killing would become a symbol of Revolutionary sacrifice and propaganda. “I am making it my duty to answer the noble invitations of patriotism and of glory that will consecrate the history of the most felicitous and most astonishing Revolution.” David said in his writings. David would also plan ceremonies like the processional transfer of Voltaire’s remains to the new Pantheon.

David’s Jacobin allegiance quickly became a problem, and he was imprisoned for treason in August 1794. He was freed from jail prior to being given amnesty in October 1795 due to bad health and a worry that he would attempt suicide.

Late Life

David’s eyesight began to deteriorate while he was in prison, but his personal and professional lives were unaffected. In November 1796, his old wife returned, and they remarried. He was elected to the Académie de peinture et de sculpture, which had succeeded the Royal Academy as France’s primary art organisation, in December 1795. His work was in high demand once more, thanks in part to his friendship with Napoleon Bonaparte, France’s new ruler. Napoleon made the artist a Knight of the Legion in December 1803, and commissioned a work celebrating his coronation as Emperor.

When Napoleon fell from power in 1815, David’s political affiliation would lead to his exile. David had no place in the Restoration monarchy; King Louis XVIII’s administration persecuted supporters of Napoleon, and David was banished from France as a result. He and his wife moved to Brussels in January 1816, where he would spend the remainder of his life.

Despite his declining health, he continued to paint, accepting portrait contracts and finishing his last major piece, Mars Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces, in 1824. Some of his students attempted to persuade him to return to France at this time, but he declined, indignant at the country that had turned him down and maybe aware that Neoclassical style was no longer fashionable there. “Never speak to me again of things I ought to do to get back,” he told one pupil who had asked his signature on an amnesty petition. I don’t have to do anything; I’ve already done everything I could for my nation.

In 1825, David died in Brussels; his wife, who was also in terrible condition, had travelled to Paris for medical treatment and was not present during his dying days. His remains was not allowed to be transferred to France for burial because of the French monarchy’s refusal. Following his wife’s death, their son allegedly placed David’s heart in her coffin and buried her in Paris. In 1989, the French government attempted to repatriate David’s bones as part of the 200th anniversary of the Revolution, but the Belgian government refused, claiming that his burial had become a historical monument.

David utilised his work to manipulate political opinion, win favour with dictatorships, and incite revolutions. His close participation in politics brought history painting into into contact with contemporary events. Later painters would be inspired to depict the modern world because of this immediacy, however the Romantics (many of whom were David’s disciples) would drastically rethink the engagement to critique those in power, portraying more emotionally packed narratives in a more painterly style.

Famous Art by Jacques-Louis David

The Oath of the Horatii

1784

The Horatii’s Oath portrays a tale from early Roman history. Three young soldiers on the left reach out to their father, promising to battle for their nation. They seem determined and united, as though to prove their sacrifice and courage, every muscle in their body is actively engaged and strongly depicted. To settle a territorial conflict between their city-states, these Roman Horatii brothers were to fight three Curatii brothers from Alba. They are prepared to battle to the death for the sake of their family and home.

Oath of the Tennis Court

1791

David launched an ambitious endeavour to commemorate the first anniversary of the Tennis Court oath, a moment of unity that sparked the revolution. Because of the colossal scale of this proposed artwork, practically life-size portraits of the principal characters were necessary. He incorporated representations of major prominent characters such as Jean-Sylvestre Bailly and Maximilien Robespierre in this preliminary drawing.

Bonaparte Crossing the Grand Saint-Bernard Pass, 20 May 1800

1800

Bonaparte Crossing the St Bernard Pass is a large-scale horse picture of the monarch that exudes total power, confidence, and optimism. Napoleon cements his position in history with two earlier generals who triumphed in this same tough military strategy; their names are carved into the rocks in the lower left corner: Hannibal and Charlemagne.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- The archetypal Neoclassical painter, David’s enormous paintings were possibly the crowning triumph of conventional historical painting.

- David combined antique topics with Enlightenment thought to produce moral exemplars in the popular Greco-Roman style.

- His linear shapes vividly depicted storylines that frequently paralleled current events.

- Despite the fundamental contrasts in these ruling regimes, David served the monarchy of Louis XVI, the post-revolutionary administration, and Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte as the preeminent painter of his time.

- He also operated a prestigious studio, where his students would eventually revolt against his leadership, planting the roots of modernism.

- David was the first French artist to combine classical topics with minimalist composition and linear accuracy.

- His paintings, which completely rejected the Rococo’s ornamental and artistic qualities, generated strong, didactic works of moral clarity with minimal distractions or visual embellishments.

- Although David is most known for his work during the French Revolution, when he sat on the National Council and coordinated propaganda, he was also a skilled politician who tailored his art to the requirements of each of his patrons.

- The Academy taught sketching; students would apprentice in a master’s studio to learn to paint.

- David’s studio became the most significant training environment for late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century artists.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.