(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1912

Died: 1956

Summary of Jackson Pollock

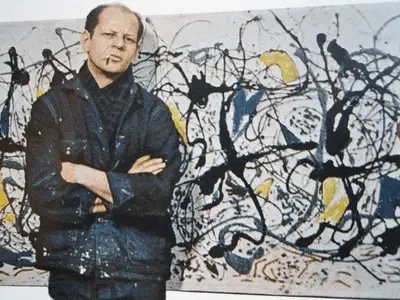

Life magazine published a major piece about Jackson Pollock in its August 8, 1949 issue, under the title “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” Could a painter who used a stick to fling paint at canvases, pouring and hurling it to create swirling vortexes of colour and line be called “great”? Pollock’s preeminence among the Abstract Expressionists has survived, fortified by the mythology of his drinking and early death, according to New York critics. His famed ‘drip paintings,’ which he began making in the late 1940s, are one of the century’s most innovative pieces of work.

Pollock was moulded into the forceful figure he would become by his harsh and unstable upbringing in the American West. Years spent creating realist murals in the 1930s taught him the potential of painting on a big scale; Surrealism provided methods to represent the unconscious; and Cubism influenced his knowledge of picture space; and later, a sequence of influences came together to bring Pollock to his mature style.

Pollock began seeing a Jungian analyst in 1939 to get help for his drinking, and his therapist encouraged him to sketch. These would eventually fuel Pollock’s paintings, and they impacted his perception of his paintings as representations of the dread of all contemporary mankind living under the shadow of nuclear war, not only as outpourings of his own mind.

Pollock’s brilliance is in creating one of the most radical abstract techniques in contemporary art history, divorcing line from colour, redefining drawing and painting categories, and inventing new ways to represent pictorial space.

Childhood

Paul Jackson Pollock, the fifth and youngest son of an Irish-Scottish family, was born in Cody, Wyoming, in 1912. When Pollock was 10 months old, his family relocated to San Diego. His father’s profession as a surveyor would compel them to travel across the Southwest several times over the next few years, until Pollock’s father abandoned the family when he was nine years old, only to return when Jackson had left home. Pollock had a difficult background, but he came to love nature – animals and the vastness of the country – and found Native American art while living in Phoenix in 1923.

Early Life

Pollock went to Los Angeles’ Manual Arts High School, where he met Philip Guston and was introduced to theosophical concepts, which influenced his subsequent interests in Surrealism and psychoanalysis. Pollock’s older brothers, Charles and Sanford, were both painters, and it was their support that drew him to New York in 1930, where he studied at the Art Students League under Regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton.

Pollock was drawn to the Old Masters in New York and began to study mural painting. He sat for Benton’s paintings at the New School for Social Research in 1930-31, where he met José Clemente Orozco, a well-known Mexican muralist. Later, he spent a summer at the New Workers School watching Diego Rivera create murals, and in 1936, he joined the Experimental Workshop of another muralist, David Alfaro Siqueiros, where he learned to use unconventional painting methods. Going West (1934-35), Pollock’s own canvas, combines several of these inspirations and is characteristic of his technique at the period. In 1937, he was appointed to the Federal Art Project’s Easel Division of the Works Progress Administration.

Pollock spent most of the 1930s in Greenwich Village with his brothers, and he was so impoverished that he had to work as a janitor and steal food to get by. However, in 1932, he was invited to the Brooklyn Museum’s 8th Show of Watercolors, Pastels, and Drawings by American and French Artists, which was his first exhibition.

Mid Life

Pollock met Lenore (“Lee”) Krasner for the first time in 1936. Pollock’s connection would eventually provide him some of the few moments of peace and contentment he had ever experienced. But it wasn’t until 1941 that the two met again, and it was then that they fell in love and married in 1945. Meanwhile, Pollock’s drinking, which had plagued him since childhood, prompted him to seek therapy as early as 1938, and by 1939, he was attending Jungian psychoanalysis. His analyst urged him to do drawings to help his rehabilitation, and the approaches and motifs in these paintings were used to promote his recuperation.

Despite his personal troubles, Pollock maintained an unwavering faith in his work. When she first saw his work in the early 1940s, Krasner was blown away and recommended him to her art instructor, Hans Hofmann. Hofmann was as excited, and the two men developed an enduring relationship as a result of their meeting. Pollock famously stated, “I don’t paint nature, I am nature.” in response to Hofmann’s suggestion that he work more from nature.

When the WPA ended in 1943, Pollock was compelled to look for work on his own. He worked as a custodian at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (later the Guggenheim Museum) and met Peggy Guggenheim, who asked him to submit art to her new gallery, The Art of This Century, among other odd jobs. Guggenheim eventually signed Pollock to a contract and offered him his first solo show in 1943, which was favourably received. Pollock had absorbed and surpassed Mexican mural art, Picasso, and Miró, according to critic Clement Greenberg.

Peggy Guggenheim commissioned a picture for her New York apartment’s entry hall at the same time. Mural (1943) was the outcome, and it was a pivotal piece in Pollock’s move from a style influenced by murals, Native American art, and European modernism to his mature drip method. And it was Guggenheim who assisted Pollock once again when he needed a down payment on an ancient farmhouse in the Long Island village of The Springs. In the fall of 1945, he and Krasner acquired the farmhouse and married in October. Distance from the city’s difficulties and temptations, Krasner thought, would provide a fantastic chance for both of them to pursue their art in solitude.

Pollock’s drip method is the subject of a lengthy and inconclusive scholarly debate, although his work was already pointing in that direction in the mid-1940s. He began to abandon the symbolic iconography of his earlier works in favour of more abstract ways of expressing himself. His experience painting Mural for Guggenheim’s apartment inspired him to create There Were Seven in Eight in 1945, a painting in which identifiable imagery was completely repressed and the surface was knitted together by a vibrant tangle of lines. In the years that followed, his approach remained brazenly abstract, and he created works such as Shimmering Substance (1946).

The next year, he eventually came up with the notion of throwing and pouring paint, and so discovered a way to achieve the light, airy, and seemingly infinite webs of colour he was aiming for. The consequence was masterpieces like Full Fathom Five (1947). Pollock had performed yet another artistic somersault, this time combining Impressionism, Surrealism, and Cubism into a single approach.

Shimmering Number 1A (1948), a larger canvas than Pollock was used to and thick with a brilliant web of colour, was the result of substance. He discovered that the ideal way to tackle works like this was to lay the canvas flat on the floor, move around it, and paint from all angles. He enabled the paint to drip and fall in weaving patterns across the surface by dipping a tiny stick, house brush, or trowel into the paint and then swiftly moving his wrist, arm, and torso. The method, which critic Harold Rosenberg coined “Action Painting,” seldom allowed the brush to come into close contact with the canvas.

“On the floor, I am more at ease,” he added. “I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting.” As a result, Pollock’s art became as much about method as it was about outcome. They became a record of his painting performance – his play in and around the canvas, where he could both enter as a participant and hover above as the artist. “”There is no accident, just as there is no beginning or end,” Pollock famously stated. I occasionally misplace a painting, but I am not afraid of making modifications or ruining the picture since a painting has its own life.”

The power of Pollock’s mature work was quickly recognised by critics. “[His] superiority to his contemporaries in this country lies in his ability to create genuinely violent and extravagant art without losing stylistic control.” Greenberg, who would become his staunchest and most influential advocate, wrote at the time. However, when Pollock’s photographs were published in magazines such as Vogue and Life, the reaction was a combination of surprise and disbelief. He was also not well-known at initially, with only a tiny group of admirers.

Late Life

Despite the fact that Pollock’s radical abstraction seemed to promise an astonishing new freedom for painting, identifiable iconography remained in the background of his works. Blue Poles (1952) has a large expanse that is stitched together with diagonal lines. Among its extraordinary range of effects, One: Number 31 (1950) preserves a distinct feeling of rhythmically moving figures. Pollock may have abandoned his youth’s realism, but he still managed to produce works that were brilliantly allegorical.

One, like many of his works from this period, creates a sense of grandeur, connecting it to the 18th-century tradition of majestic landscape painting. It also has the appearance of being dappled with light, similar to Monet’s works, and many commentators have suggested that Pollock was influenced by the French Impressionist.

Pollock’s interest in figurative imagery never waned – as he once put it, “Part of the time, I’m extremely representational, and some of the time, I’m not. When you’re painting from your subconscious, though, figures are going to appear.” Figuration began to resurface in his work as early as the late 1940s. By 1950, he had returned to sketching, revisiting some of his earlier ideas and producing a series of mostly black and white poured paintings, despite his increasing alcoholism. Some, like Yellow Islands (1952), are very abstract with splashes of colour; others, like Echo (Number 25, 1951), are calligraphic in style with only a smattering of figurative elements; and yet others contain distinct pictures of heads.

In his final years, his personal problems only worsened. He quit Betty Parsons Gallery and struggled to find another gallery because of his notoriety. In 1954, he painted very little, stating that he had run out of things to say. Krasner travelled to Europe in the summer of 1956 to get away from Pollock, and shortly after, he began a relationship with Ruth Kligman, a 25-year-old artist whom he met at the Cedar Bar. Then, on the night of August 11, 1956, while out drinking with Kligman and her friend, Edith Metzger, Pollock lost control of the automobile, killing himself and Metzger and wounding Kligman badly.

Other painters were most affected by Pollock’s immediate legacy. His art included aspects of Cubism, Surrealism, and Impressionism while transcending all of them. Even greats like de Kooning, who stayed closer to Cubism and clung to figurative imagery, seemed to fall short in comparison. And, just as Pollock had struggled with Picasso, the finest among succeeding generations of artists would have to take on his achievement.

Famous Art by Jackson Pollock

Going West

1935

Going West encapsulates several of Pollock’s early passions. During the 1930s, he was heavily influenced by his master Thomas Hart Benton’s American Regionalism, but Going West has a dark, almost mystical aspect that Pollock appreciated in another American visionary painter, Albert Pinkham Ryder. El Greco and Van Gogh’s emotional intensity is evoked by the whirling patterns that compose the image. Pollock’s developing style is linked to his own beginnings through this picture of a pioneer going West. While the picture has a gothic feel to it, it is said to be based on a family photo of a bridge in Cody, Wyoming, where Pollock was born.

Autumn Rhythm: Number 30

1950

Pollock’s solo exhibition in 1950 drew a lot of attention, despite the fact that just one picture was sold. It was named one of the top three exhibits of the year by Art News, and Cecil Beaton conducted a renowned fashion shot in the exhibition space, which was later published in Vogue. Autumn Rhythm was one of the key pieces in the exhibition. Like so many of Pollock’s paintings, he started with a linear structure of diluted black paint that seeped though the unprimed canvas in several places. More skeins of paint in various colours were placed over this, with thick and thin, bright and dark, straight and curved, horizontal and vertical lines.

The Deep

1953

Pollock’s art and personal life underwent significant shifts during the 1950s. He began shunning colour in 1951 and began painting solely in black, yet his output progressively deteriorated as his drinking took over his life. The Deep conjures us images of a chasm – an abyss to be avoided or lost in. Pollock’s direct interaction with the canvas was reintroduced with the use of layered brush strokes to build up white paint. Drips are still visible, and they’ve begun to form a web that floats above the abyss. Pollock was definitely seeking for a new method, an image to produce, anxious to break away from his hallmark style, yet his final works are neither a start nor a finish.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Life magazine published a major piece about Jackson Pollock in its August 8, 1949 issue, under the title “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”

- Could a painter who used a stick to fling paint at canvases, pouring and hurling it to create swirling vortexes of colour and line be called “great”?

- Pollock’s preeminence among the Abstract Expressionists has survived, fortified by the mythology of his drinking and early death, according to New York critics.

- His famed ‘drip paintings,’ which he began making in the late 1940s, are one of the century’s most innovative pieces of work.

- Pollock was moulded into the forceful figure he would become by his harsh and unstable upbringing in the American West.

- Years spent creating realist murals in the 1930s taught him the potential of painting on a big scale; Surrealism provided methods to represent the unconscious; and Cubism influenced his knowledge of picture space; and later, a sequence of influences came together to bring Pollock to his mature style.

- Pollock began seeing a Jungian analyst in 1939 to get help for his drinking, and his therapist encouraged him to sketch.

- These would eventually fuel Pollock’s paintings, and they impacted his perception of his paintings as representations of the dread of all contemporary mankind living under the shadow of nuclear war, not only as outpourings of his own mind.

- Pollock’s brilliance is in creating one of the most radical abstract techniques in contemporary art history, divorcing line from colour, redefining drawing and painting categories, and inventing new ways to represent pictorial space.

Born: 1912

Died: 1956

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.