Historical Context of Art Therapy

Art therapy, initially tied to PTSD, started showing promise for other mental health conditions. In hospitals, therapists began integrating drawing and painting with traditional talk therapies to help patients articulate feelings they couldn't easily express in words. This was particularly useful for young children and trauma survivors, who often struggled to communicate their emotions verbally.

The practice grew beyond military and healthcare settings. By the late 20th century, art therapy had branched out to schools, community centers, and private practices. Children with ADHD, adults with anxiety, and cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy all experienced the benefits of drawing and other artistic endeavors. With each pencil stroke or brush dab, patients found a medium through which they could explore and understand their feelings.

Around the same time, research into the effects of art therapy began to flourish. Studies indicated that the act of drawing could significantly reduce cortisol levels, a marker of stress.1 Patients reported feeling calmer and more in control after art sessions. Importantly, they also felt a sense of accomplishment and pride in their creations, boosting their self-esteem and providing a respite from their struggles.

Art therapists didn't stop at drawing and painting. They incorporated other forms of creative expression like sculpture and collage, adapting their methods to fit individual needs. For instance, sculpting with clay became a tactile way for patients to connect with their bodies and release pent-up tension. Collaging from magazine cutouts offered a visual way to piece together fragmented memories or aspirations for the future.

Therapists also started customizing art activities to target specific symptoms of depression. One common practice involved having patients draw or paint their "emotional landscape," a visual representation of their inner state. This provided therapists with a window into the patient's psyche and enabled patients to gain new insights into their own emotional world.

With each evolution, art therapy's effectiveness extended further. In care homes, drawing sessions have alleviated feelings of loneliness among the elderly, providing a point of connection and shared experience. Art therapy even found its way into correctional facilities, helping inmates process their emotions and envision a future beyond incarceration.

Art therapy's appeal lies in its simplicity and accessibility. Unlike traditional therapies that may feel intimidating or intrusive, drawing offers a familiar and approachable way for individuals to express themselves. The tactile pleasure of moving a pencil across paper, releasing emotions through colors and strokes, makes art a powerful tool for achieving emotional clarity and relief.

As art therapists continue to explore new methodologies and mediums, the foundational act of drawing remains a valuable tool in the mental health toolkit. The journey of art therapy from its origins with PTSD-stricken soldiers to its modern applications in treating depression underscores the lasting impact of drawing on emotional healing.

Mechanisms of Art Therapy

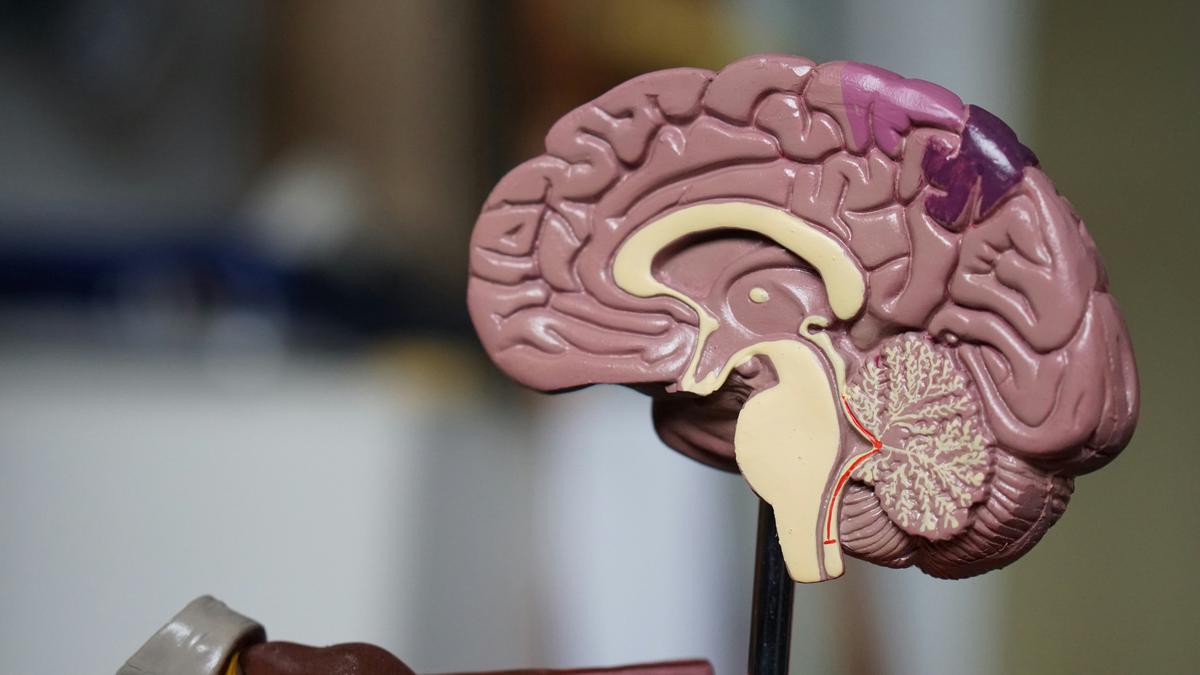

Understanding how art therapy exerts its positive influence on mental health requires examining its psychological and neurological underpinnings. Drawing and other forms of artistic expression engage the brain in unique ways, tapping into areas responsible for emotion, memory, and reward.

When individuals engage in drawing, several processes occur:

- The physical act of drawing can activate the brain's reward pathways. During creative activities, the brain releases dopamine, the "feel-good" neurotransmitter. Dopamine enhances pleasure and satisfaction and plays a crucial role in motivation and attention. The brain associates the creative process with positive reinforcement, paving the way for improved mood and emotional well-being.

- Neurologically speaking, the act of drawing engages the brain's limbic system, particularly the amygdala, which is closely tied to processing emotions. As individuals translate complex feelings into shapes, lines, and colors, they tap into deep-seated emotions in a tangible way. This externalization offers relief, similar to verbalizing a long-held worry, which can lessen its emotional burden. Art therapist Cathy Malchiodi likens this process to "taking out the emotional trash," allowing individuals to cleanse their minds and make room for healing.

- Creating art induces a state of flow—a focused immersion where time seems irrelevant, and concentration is heightened. This state is often described as deeply satisfying and stress-relieving. Flow reduces stress by diverting attention away from distressing thoughts, offering a temporary escape and allowing the mind to reset.

The mindfulness aspect of art therapy is significant. Drawing requires a focus on the present moment, a principle mirrored in mindfulness practices. This present-centered awareness helps reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression by promoting a non-judgmental acceptance of one's thoughts and feelings.2 Drawing serves as both a creative and meditative practice, engendering a sense of calm and balance.

Experts have also noted the cognitive benefits of engaging in art. Creating art can improve problem-solving skills and enhance cognitive flexibility—abilities that are often diminished in individuals with depression. Enhanced cognitive flexibility allows for more adaptable thinking, helping patients break out of negative thought patterns and develop healthier coping mechanisms.

From a psychological perspective, the therapeutic alliance created during art therapy sessions contributes significantly to its effectiveness. This alliance, built on trust and empathy, enables therapists to guide patients through their creative journey, facilitating meaningful self-exploration and insight. The supportive environment of art therapy offers emotional validation, fostering resilience and self-empowerment.

The communal aspect of many art therapy programs also plays a vital role. Engaging in art-making within a group setting fosters social connections and reduces feelings of isolation. The collaborative nature of group art projects offers a sense of belonging and shared purpose, which can counteract the loneliness often associated with depression.

In conclusion, the mechanisms by which drawing and art therapy alleviate depression are multifaceted, involving psychological, neurological, and social elements. Whether through the activation of reward pathways, the induction of mindfulness states, or the fostering of human connection, art therapy provides a holistic approach to emotional healing.

Case Studies and Personal Experiences

Andrea Cooper, a retired graphic designer and folk musician, found herself increasingly isolated during the coronavirus pandemic, severely impacting her mental health. Her sense of connectedness ebbed as social events transitioned to digital platforms and face-to-face interactions dwindled. The toll on her mental well-being became so severe that she required hospitalization to manage her escalating depression.

Andrea's introduction to art therapy initially sparked skepticism. As an artist, she was oddly resistant to the structured prompts provided by her art therapist, questioning their efficacy in addressing her emotional turmoil. However, as she immersed herself in the creative process, her skepticism waned. One therapeutic prompt about growth resonated deeply, compelling her to draw a pair of pruning shears cutting a stem off a rose bush. The act of "pruning" symbolized the harsh but necessary steps she needed to take to foster personal growth and recovery—a powerful visual metaphor that facilitated a breakthrough in her healing journey.

Another notable story is that of Michael, a middle-aged man grappling with the dual burdens of chronic depression and anxiety. His therapist introduced him to the concept of creating an "emotional landscape" through drawing. At first hesitant and unsure of his artistic abilities, Michael quickly discovered that his sketches provided a new avenue for self-expression. Over a few months, his tentative lines evolved into more confident strokes, and his emotional landscapes transitioned from tumultuous storms to calmer, more centered scenes of serenity. This creative journey helped Michael externalize his feelings and offered him a sense of accomplishment and empowerment as he witnessed his emotional progress mirrored in his art.

Emma, a young woman dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) stemming from childhood abuse, found solace in creating collages. These visual narratives allowed her to piece together fragmented memories in a way that felt safe and controlled. Through her art, Emma was able to reconstruct her self-image and gain insights into her experiences without the confronting need to verbalize her trauma. This visual storytelling provided a means to explore her past and move toward healing.

Jose, an inmate in a correctional facility, began art therapy as a means to deal with anger and depression. The structured environment of the prison offered little emotional outlet, and Jose's pent-up frustrations often led to conflicts. Drawing provided a transformative outlet. His early pieces were characterized by dark, aggressive themes, but as he continued with his sessions, his artwork grew more nuanced. Depicting scenes of nature and family, Jose was able to reconnect with a sense of hope and humanity that prison life had suppressed. His art became a vehicle for envisioning a different future, offering him a lifeline beyond his current circumstances.

The communal aspect of art therapy also cannot be underestimated. In group settings, the shared act of creation forms bonds of empathy and understanding. It combats the isolation inherent in depression. Workshops and group sessions wherein participants share and discuss their artwork build a sense of community and collective healing. For Lily, a teenager who felt alienated due to her mental health struggles, participating in a group art therapy program provided a sense of belonging. This communal support system, built through shared creative endeavors, significantly enhanced her coping mechanisms and opened new pathways to emotional connection.

In exploring these case studies and personal experiences, it becomes evident that drawing is a cornerstone of comprehensive mental health therapy. Whether through detailed, structured art sessions or spontaneous, unscripted creations, individuals across various life stages and conditions have harnessed this powerful medium to mitigate the effects of depression. Their stories serve as a testament to the enduring, multifaceted impact of art therapy in fostering emotional healing and well-being.

Art Therapy Techniques and Approaches

Art therapists employ a wide array of techniques to connect with their patients, each carefully chosen to address individual needs and therapeutic goals. Among these methods, unstructured doodling stands out for its simplicity and accessibility. This free-form activity invites individuals to let their creativity flow without the constraints of defined structures or expectations. By putting pen to paper and allowing thoughts to manifest as spontaneous lines and shapes, unstructured doodling helps patients tap into subconscious emotions, revealing underlying concerns or thoughts that might be challenging to articulate verbally.

Guided drawing prompts blend the intuitive freedom of creativity with a therapeutic framework. Unlike unstructured doodling, guided prompts provide a thematic or directive focus designed to elicit specific insights or reflections. Therapists might ask patients to draw their "safe place," a representation of their fears, or a visualization of their goals. These prompts serve as conversation starters that lead to deeper psychological exploration.

Creating collages is another potent tool in an art therapist's toolkit. This technique involves assembling images, text, and textures from various sources like magazines, newspapers, or photographs. The choices patients make—what they include, exclude, emphasize, or obscure—provide significant insights into their inner worlds. Collages allow patients to piece together fractured memories or envision aspirational futures in a way that feels both safe and empowering.

Thematic art projects tailored to address specific symptoms of depression are also notable. These could include activities designed to cultivate gratitude, such as creating "gratitude jars" filled with illustrated entries of things the patient appreciates. Such projects encourage a shift in focus from negative to positive experiences, subtly rewiring the brain towards more optimistic thinking patterns.

Personalization is paramount in art therapy sessions. Therapists continually assess and adapt techniques to meet the evolving needs of their patients. For some, hands-on, sensory-rich activities like sculpture might be more effective. Sculpting with clay, for example, engages the creative mind and offers a physical, tactile experience that can ground patients, providing a tangible way to exert control and release tension.

Expressive writing, integrated into visual art projects, can provide a dual outlet for emotions. Patients might create visual journals, combining sketches, paintings, or collage with written reflections. This allows them to process and articulate their thoughts through multiple channels, deepening their self-awareness and emotional insight.

Group art therapy introduces a collaborative dynamic that fosters social interaction and collective healing. Shared projects encourage participants to work together, enhancing their sense of community and connection. These collective efforts build a supportive environment where individuals can share their struggles and triumphs through artistic expression.

Ultimately, the choice of technique depends on the individual's needs, preferences, and therapeutic objectives. The success of art therapy lies in its ability to offer a personalized and flexible approach to healing—one that honors the uniqueness of each person's journey. Through various creative methods, art therapy continues to provide invaluable paths to emotional clarity and resilience.

Scientific Evidence and Research

A growing body of research exploring the impact of drawing and art therapy on depression offers compelling evidence supporting its efficacy. A 2016 study published in the Journal of the American Art Therapy Association examined the therapeutic effects of drawing for individuals diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD). The drawing group showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms, measured using standardized clinical scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). The therapeutic gains from drawing activities were comparable to those achieved through traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).1

Similarly, a 2018 meta-analysis published in Psychological Bulletin aggregated findings from 29 empirical studies on art therapy's impact on depression. The meta-analysis highlighted that art therapy consistently resulted in moderate to large improvements in depressive symptoms across diverse demographic groups. It emphasized that engaging in creative processes like drawing facilitated emotional expression and processing—crucial elements in alleviating depressive states.2

Another noteworthy study, published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, investigated the neurological effects of art-making using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The findings revealed that drawing activated the prefrontal cortex and limbic regions, areas associated with emotional regulation and cognitive processing. Drawing also stimulated the brain's reward system, similar to the release of dopamine experienced during pleasurable activities. This neurobiological response offers a tangible explanation for the mood-enhancing effects of drawing.3

These scientific findings collectively create a robust foundation for the integration of art therapy into mainstream mental health treatment. They provide a clear, data-driven rationale for the implementation of drawing-based interventions as a viable therapeutic approach for those grappling with depression. As researchers continue to explore the intricate relationship between creative expression and psychological health, the evidence strongly suggests that drawing is more than an artistic endeavor—it's a formidable ally in the battle against depression.

Despite the positive outcomes observed, it's essential to acknowledge the limitations inherent in the current research. Variables such as sample size, the subjective nature of artistic interpretation, and varied methodological approaches indicate that further, more standardized studies are necessary to reinforce these initial findings. However, the overwhelming consensus within the scientific community remains optimistic, advocating for drawing and art therapy as vital components of comprehensive mental health care.

Challenges and Limitations

While the benefits of art therapy and drawing in alleviating depression are compelling, several challenges and limitations merit consideration.

One significant challenge lies in the need for more large-scale studies to substantiate the preliminary positive findings. Although existing research provides promising results, many studies on art therapy involve small sample sizes or lack rigorous control groups. For art therapy to gain broader acceptance within the medical community, extensive, well-structured research is needed to establish its efficacy unequivocally.

Another critical limitation is the variability in individual responses to art therapy. Factors such as personal comfort with creative expression, previous artistic experience, cultural background, and personality traits all play a role in determining the success of the therapy. Consequently, personalization and flexibility in therapeutic techniques are vital to cater to diverse needs and preferences.

Art therapy can be immensely beneficial, but it is not a standalone cure for depression. It works best when integrated with other treatment modalities, such as:

- Medication

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Talk therapy

Art therapy can complement these approaches by providing additional avenues for expression and exploration, but it should not replace conventional treatments.

The subjective nature of art interpretation also presents a challenge. Unlike more quantifiable therapeutic interventions, the meaning and impact of a piece of art can vary greatly between individuals. While this subjectivity allows for personalized and unique therapeutic experiences, it also makes standardizing and measuring results difficult.

Access to art therapy can be limited by practical constraints such as availability of trained professionals, funding, and healthcare policies. Efforts to broaden access to art therapy must address these logistical issues, ensuring that more individuals can benefit from this therapeutic approach.

The emotional process of creating art can sometimes be intense and overwhelming, particularly for individuals dealing with severe trauma or deep-seated psychological issues. Skilled art therapists must be equipped to handle emotional crises that may arise during sessions, ensuring a safe and supportive environment for their patients.

In summary, while art therapy holds tremendous potential for managing and alleviating depression, it is accompanied by challenges that must be acknowledged and addressed. More large-scale research, individualized approaches, integration with other treatments, overcoming practical barriers, and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration are all essential steps toward fully realizing the therapeutic power of art.

Drawing and art therapy offer a powerful means of emotional healing. As research continues to support its benefits, the role of art in mental health care becomes increasingly clear. Embracing this creative form of therapy can lead to profound improvements in emotional well-being.