(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1862

Died: 1918

Summary of Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt, an Austrian painter, was known for his eccentricities. Friederika Maria Beer-Monti, a supporter of Klimt’s, once came to his studio to have her picture painted while wearing a flamboyant polecat jacket made by Klimt’s Wiener Werkstätte colleagues. You’d think Klimt would approve, but he made her turn it inside out to reveal the crimson silk lining, and he painted her that way. Klimt, Vienna’s most famous artist at the time, had the power to do so. He is regarded as one of the finest decorative painters of the twentieth century, as well as the creator of one of the most important works of erotic art.

Initially successful in his academic pursuits for architectural projects, his experience with more current European art movements inspired him to establish his own very distinctive, diverse, and frequently surreal style. Klimt’s role as co-founder and first president of the Vienna Secession guaranteed that the movement’s influence grew significantly. Klimt never sought out controversy, but his work’s extremely contentious subject matter in a historically conservative creative centre plagued his career.

Klimt rose to prominence as a decorative painter of historical themes and people after receiving several orders to decorate public buildings. The flattened, shimmering patterns of his nearly-abstract compositions, now known as his “Golden Phase” works, eventually became the true focus of his paintings as he worked to develop the ornamental characteristics.

Klimt was a great exponent of the equality of the fine and decorative arts, despite being a “fine art” painter. He accepted several of his best-known projects that were meant to match other parts of a full interior, therefore producing a Gesamtkunstwerk, having obtained some of his early success by painting inside a larger architectural framework (total work of art). Later in his career, he collaborated with artists from the Wiener Werkstätte, an Austrian design collective dedicated to improving the quality and aesthetic appeal of common products.

Klimt was one of the most significant founders of the Vienna Secession in 1897, serving as its first president, but he was picked for his young personality and desire to confront authority rather than his finished oeuvre, which was rather modest at the time. His tenacity and international recognition as the most renowned Art Nouveau painter contributed significantly to the Secession’s early success – but also to the movement’s rapid decline when he departed in 1905.

Although Klimt’s art is now well-known, he was mostly ignored for much of the twentieth century. Klimt’s works for public areas sparked a storm of controversy in his day, with allegations of obscenity levelled against them owing to their sexual nature, finally forcing him to resign from government commissions entirely. His paintings are equally provocative, expressing his voracious sexual hunger to the fullest extent possible.

Childhood

Gustav Klimt was the second of seven children born to Ernst Klimt, a gold engraver from Bohemia, and Anna Finster, an aspiring but unsuccessful musical singer, in the tiny neighbourhood of Baumgarten, southwest of Vienna. Because work was limited in the early years of the Habsburg Empire, especially for minority ethnic groups, the Klimt family was destitute. This was owing in part to the 1873 stock market crisis.

Between 1862 and 1884, the Klimts relocated five times, constantly looking for a cheaper place to live. In addition to financial difficulties, the family had to deal with a lot of sorrow at home. Anna Klimt, Klimt’s younger sister, died at the age of five in 1874 after a protracted illness. After succumbing to religious fervour, his sister Klara suffered a mental collapse not long after.

Klimt and his two brothers, Ernst and Georg, showed early signs of creative ability. Gustav, on the other hand, was picked out by his teachers as a particularly gifted draughtsman while in secondary school. A relative persuaded him to take the admission exams for the Kunstgewerbeschule, the Viennese School of Arts and Crafts, when he was fourteen years old, and he passed with honours. He subsequently revealed that he planned to become a drawing master and teach at a Burgerschule, the Viennese equivalent of a basic public secondary school, which he had attended.

Klimt began his official education in Vienna at a time when the city was experiencing major transformations. The ruins of the ancient mediaeval defence walls that surrounded the core section of the city were destroyed in 1858, leaving a huge circular expanse that was rebuilt as a series of broad boulevards known as the Ringstrasse (“ring street”). The Ringstrasse was bordered with trees and big bourgeois apartment homes during the following thirty years, as well as numerous new structures housing different civic and imperial government organisations, such as theatres, art museums, the University of Vienna, and the Austrian Parliament building.

Vienna was experiencing a Golden Age of industry, research, and science, propelled by modern breakthroughs in these disciplines, with the newly constructed municipal railway, the introduction of electric street lighting, and city engineers rerouting the Danube River to minimise floods. Vienna, on the other hand, lacked a revolutionary spirit when it came to the arts.

Early Life

Klimt never questioned or criticised the Kunstgewerbeschule’s curriculum or teaching techniques, which were quite typical for their day. He was tasked with precisely replicating embellishments, patterns, and plaster castings of ancient sculptures after receiving extensive sketching instruction. Only until he had shown himself in this area was he allowed to draw figures from life. Klimt wowed his teachers from the start, and he was immediately accepted into a special painting class, where he shown significant aptitude for painting live figures and working with a range of materials. Close examinations of the works of Titian and Peter Paul Rubens were also part of the young artist’s education.

Klimt also had access to the Vienna Museum of Fine Arts’ extensive collection of paintings by Spanish artist Diego Velázquez, whose work he admired so much that he subsequently said, “There are only two painters: Velázquez and I.”

Klimt also admired Hans Makart (the most famous Viennese historical painter of the time), especially his style, which incorporated dramatic light effects and a clear love of theatricality and pomp. Klimt is said to have paid one of Makart’s attendants to get him inside the painter’s studio so that he may examine the newest works in progress while still a student.

Klimt’s painting class was joined by his younger brother Ernst and a young painter named Franz Matsch, another brilliant Viennese artist who specialised in large-scale decorative works, just before he left the Kunstgewerbeschule. Klimt and Matsch finished their studies in 1883 and hired a big studio in Vienna together. Despite his early success and the relocation, Klimt continued to live with his parents and sisters. Klimt and Matsch quickly established themselves as highly sought-after painters among the city’s cultural elite, which included renowned architects, social leaders, and government officials.

Klimt and Matsch were commissioned to produce four paintings for a Viennese architectural business specialised in theatrical design by their painting professor, Ferdinand Laufberger, as early as 1880.

Despite the high demand, Klimt and Matsch’s services were not well compensated. When Klimt, his brother Ernst, and Matsch were tasked with decorating the grand stairwell of the new Burgtheater, they discovered that their contract wouldn’t cover the price of hiring models, so they sought the help of friends and family. Today, Hermine and Johanna Klimt (together with all three painters) may be seen among the audience at Shakespeare’s theatre, where their brother Georg portrays the dying Romeo. This is Klimt’s sole surviving self-portrait, by the way.

Mid Life

By the end of 1892, both Gustav’s father, Ernst Klimt, and his younger brother, Ernst, had died, the latter unexpectedly from pericarditis. Gustav was left financially responsible for his mother, sisters, brother’s widow, and their baby daughter as a result of these deaths. Helene Flöge, the widow of his brother Ernst – to whom he had only been married for fifteen months – and her middle-class family had houses in both the city and the country, where Klimt became a frequent visitor. Klimt quickly developed a close connection with Helene’s sister, Emilie Flöge, that would last the rest of his life and serve as the inspiration for one of his most renowned portraits.

Following the deaths of his brother and father, Klimt’s output decreased. Klimt also began challenging academic painting traditions, which caused a schism between him and his long-time collaborator Matsch. Matsch was commissioned to paint the ceiling of the newly completed Great Hall of the University of Vienna by the Artistic Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Education in 1893. Klimt ultimately joined the project (either at Matsch’s invitation or at the Ministry’s request), but it would be their final cooperation.

The university commissioned Klimt to paint three huge ceiling paintings for the Great Hall, comprising Philosophy (1897-98), Medicine (1900-01), and Jurisprudence (1900-01). (1899-1907). Klimt chose a highly ornate symbolism that is difficult to decipher for these paintings, much to the astonishment of his commissioners, signalling a dramatic shift in his approach toward painting and art in general. Klimt’s University paintings sparked a lot of debate, partly because of the nuance of some of the figures in Medicine, and partly because of allegations that the subject matter was unclear.

The University paintings were never placed, and Klimt decided never to accept another public commission as a result of the dispute.

Klimt’s work on the paintings at the University of Vienna coincided with a rift in the Vienna art scene. He abandoned his membership in the Kunstlerhaus, Vienna’s main society of artists, in 1897, along with numerous other contemporary painters and designers. Klimt had been a member since 1891. Klimt and his fellow modernists protested that the Kunstlerhaus, which took a commission on works exhibited there, was denying them the same rights of displaying work there because the Kunstlerhaus, which took a commission on works displayed there, favoured the better-selling conservative works.

In 1897, the modernists reunited and founded the Vienna Secession (also known as the Union of Austrian Artists). Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and Joseph Maria Olbrich were all members of the ensemble. Klimt was elected as the Secession’s first president. Its founding principles were to provide an outlet for young and unconventional artists to show their work; to expose Vienna to great works of foreign artists (specifically the French Impressionists, which the Kunstlerhaus had failed to do); and to publish a periodical, eventually titled Ver Sacrum (“Sacred Spring”), which took its name from the Roman tradition of cities sending younger emissaries to Rome.

Through a series of exhibits, the Secession swiftly established itself in the city’s creative landscape, with Klimt playing a key part in their planning. Many of them included work by international contemporary artists who were invited to join the group as corresponding members. Given that the Viennese had little to no exposure to modern art, the shows earned widespread acclaim and sparked remarkably little debate.

In 1902, the Secessionists staged their 14th exhibition, a celebration of the musician Ludwig van Beethoven, for which Klimt created his renowned Beethoven Frieze, a huge and intricate piece that, ironically, made no apparent reference to any of Beethoven’s compositions. Instead, it was viewed as a sophisticated, poetic, and extremely elaborate metaphor of the artist as God.

Though the Secession was dedicated to the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or a completely and harmoniously designed environment, it attempted to keep art separate from commercial concerns, which proved problematic for its members, particularly decorative artists, whose work in designing useful objects necessitated a commercial outlet in order to be successful. In 1903, two of the group’s most renowned members, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, founded the Wiener Werkstätte, a new organisation committed to the promotion and design of ornamental arts and architecture for such purposes.

Klimt, who was close to both Hoffmann and Moser, would later participate on a number of Werkstatte projects, including the monumental multi-panel tree-of-life painted frieze for the Palais Stoclet in Brussels, which was the Werkstatte’s biggest Gesamtkuntswerk between 1905 and 1910.

Klimt and a number of his friends withdrew from the Vienna Secession in 1905, citing a disagreement about the group’s use of local galleries to promote their work, which were not particularly strong in Vienna. Despite having their own exhibition venue, the Secessionists struggled to sell their art due to a lack of a centralised location.

The Klimtgruppe (Klimt and his supporters, including Moser and Josef Maria Auchentaller) proposed that the Secession purchase the Gallery Miethke, but the proposal was rejected by one vote when it was put to the membership, as the opposition wanted to keep the Secession completely separate from commercial interests. Despite the fact that the Klimtgruppe’s resignation stripped the Secession of its most internationally prominent members, it has reinvented itself many times since then – often coinciding with changes in leadership – and is now the only Austrian artist-run society dedicated to the promotion of contemporary art.

Late Life

Klimt’s unique style, which richly blended aspects of both the pre-modern and modern eras, attained full maturity between 1898 and 1908, while working as a member of the Secession and on commissions for the University. During these years, he created some of his most renowned works, which have come to be known as his “Golden Phase,” so named because of Klimt’s frequent use of gold leaf.

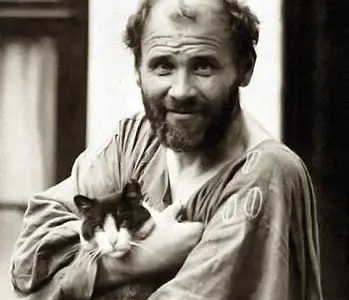

Field of Poppies (1907), The Kiss (1907-08), and Pallas Athene (1898), Judith I (1901), and Adele Bloch-Bauer I are among these works (1903-07). Despite the acclaim they now have, their response at the time was not always warm: one critic joked that Bloch-Bauer I was “more blech than Bloch” when he first saw it (“blech” actually being the German word for tin). Klimt was the early-20th-century male version of the classic crazy cat woman, so if he disliked the reaction to his paintings, he was probably pleased that critics never got to see his sketchbooks.

His sketchbooks were frequently coated in cat urine, which he claims is the finest fixative.

Klimt spent the last decade of his life dividing his time between his studio and garden in Heitzing, Vienna, and the Flöge family’s country house, where he and Emilie spent a lot of time together. Although they had an undeniable love relationship, it is commonly assumed that they never gave in to sexual yearning.

Klimt’s hatred for written language did not diminish as a result of their closeness: in one letter to Emilie, he was so upset that he simply exclaimed, “To hell with words!” When it came to locations he had seen, Klimt was similarly brief and unflattering; on one trip to Italy, he could only remark to Emilie that “there is much that is pathetic in Ravenna – the mosaics are tremendously splendid.”

Many of Klimt’s magnificent (but sometimes underestimated) en plein air landscape paintings, such as The Park (1909-10), were created during these summers, typically from the vantage point of a rowboat or an open field. Klimt had two passions in life: painting and women, and he seemed to have an insatiable desire for both. Klimt’s personal life, which he took great efforts to keep private, has become the topic of much conjecture among critics and historians, particularly considering Klimt’s numerous portraits of women.

In many cases, there has been no consensus on Klimt’s relationship with specific ladies; although many accounts swear by Klimt’s personal liaisons, others – in part owing to a lack of clear proof – deny that Klimt and those same sitters had any romantic involvement.

While Klimt’s subject matter remained the same throughout his final years, his painting manner changed dramatically.

The artist began utilising delicate colour combinations, such as lilac, coral, salmon, and yellow, in place of gold and silver leaf and decoration in general. During this period, Klimt also created an astonishing amount of drawings and sketches, the bulk of which were of female nudes, some of which were so sexual that they are rarely displayed today. At the same time, several of Klimt’s later portraits have been lauded for the artist’s increased focus on character and ostensibly renewed care for resemblance.

Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912) and Mada Primavesi (1913), as well as the curiously sensuous The Friends (c. 1916-17), depict a lesbian pair – one nude and the other dressed – amid a stylised backdrop of birds and flowers.

Klimt suffered a stroke on January 11, 1918, which left him paraplegic on his right side. Klimt fell into depression and caught influenza while bedridden and unable to paint or even draw. He died on February 6th, one of the more well-known casualties of the flu epidemic that year.

Klimt never married, never painted a self-portrait for the purpose of it, and never claimed to be a revolutionary in the field of painting. Klimt did not travel widely, but he did leave Austria on many occasions to visit other European countries (although on the one occasion he visited Paris, he left thoroughly unimpressed). Klimt’s major goal with the pioneering Secession was to draw attention to contemporary Viennese artists, and via them, to the far larger world of modern art outside Austria’s boundaries. Klimt is credited for assisting in the transformation of Vienna into a major centre for culture and the arts at the turn of the century.

Gustav Klimt Facts

How much is The Kiss by Gustav Klimt worth?

The auction price of 25,000 crowns (approximately $240,000 in today’s money) was five times greater than any other picture in Vienna had ever fetched.

How much are Gustav Klimt paintings worth?

Multiple auctions of Gustav Klimt’s work have yielded values ranging from $7 USD to $87,936,000 USD based on the artwork’s size and media.

Who was Gustav Klimt and what was his artwork about?

Artist Gustav Klimt, born in Austria in 1862, is most known for his flamboyant, sensual paintings that were considered a rebellion against the academic tradition of art at the time. The Kiss and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer are two of his best-known works.

What was Gustav Klimt famous for?

The Austrian painter Gustav Klimt is credited with starting the Vienna Sezession school of painting. Klimt founded his own studio in 1883 after completing his studies at the Vienna School of Decorative Arts.

How much money did Oprah make when she sold her Gustav Klimt painting for $150 million?

Winfrey sold the Klimt painting for an incredible $150 million in what Bloomberg labelled “one of the greatest private art purchases of 2016.” The Color Purpleactor made $62.1 million in profit from the sale, a return on investment of 71%.

Famous Art by Gustav Klimt

The Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater

1888-1889

Klimt and his colleague Franz Matsch were commissioned by the Vienna city council to paint pictures of the old Burgtheater, the city’s opera house, which was erected in 1741 and was set for demolition once its successor was completed in 1888, as a record of the theater’s existence. Unlike Matsch’s equivalent, which depicts the stage of the Burgtheater from a seat in the auditorium, Klimt’s approach reveals the whole arrangement of loges and auditorium floor seats, as well as the ceiling ornamentation – an unusual decision, but one that is architecturally significant.

Medicine

1900-1901

Klimt was commissioned by the Ministry of Culture in 1894 to create paintings for the University of Vienna’s new Great Hall, which had just been completed on the Ringstrasse. Klimt was tasked with painting three gigantic paintings on the subjects of philosophy, medicine, and law, respectively. Klimt had joined the Secession and abandoned the Old Burgtheater’s naturalism to question the traditional subject matter by the time he began painting the paintings four years later. The underlying subject that was meant to tie the three University paintings together was “the triumph of light over darkness,” and Klimt was given creative licence within that framework.

Adele Bloch-Bauer I

1903-1907

Many believe this piece to be Klimt’s best, and it may also be his most well-known because of its key part in one of the most notorious incidents of Nazi art theft. Adele Bloch-Bauer, the wife of Viennese banking and sugar tycoon Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, was one of Klimt’s favourites among the numerous ladies he painted from life, sitting for two portraits and acting as the basis for several other works, including his renowned Judith I. (1901). Despite the fact that Klimt was supposed to be intimately connected with a number of the ladies he painted, his extraordinary secrecy means that historians are still divided on the nature of his connection with Adele Bloch-Bauer.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Gustav Klimt, an Austrian painter, was known for his eccentricities.

- Friederika Maria Beer-Monti, a supporter of Klimt’s, once came to his studio to have her picture painted while wearing a flamboyant polecat jacket made by Klimt’s Wiener Werkstätte colleagues.

- Klimt, Vienna’s most famous artist at the time, had the power to do so.

- He is regarded as one of the finest decorative painters of the twentieth century, as well as the creator of one of the most important works of erotic art.

- Klimt’s role as co-founder and first president of the Vienna Secession guaranteed that the movement’s influence grew significantly.

- Klimt never sought out controversy, but his work’s extremely contentious subject matter in a historically conservative creative centre plagued his career.

- Although Klimt’s art is now well-known, he was mostly ignored for much of the twentieth century.

- Klimt’s works for public areas sparked a storm of controversy in his day, with allegations of obscenity levelled against them owing to their sexual nature, finally forcing him to resign from government commissions entirely.

- His paintings are equally provocative, expressing his voracious sexual hunger to the fullest extent possible.

- Despite his celebrity and generosity in teaching younger artists like as Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, Klimt generated practically no direct disciples, and his work has remained very personal and distinctive until this day.

- Even if many of them were unfamiliar with Klimt’s work, his paintings share many stylistic and subject elements with the Expressionists and Surrealists of the interwar years.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.