(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

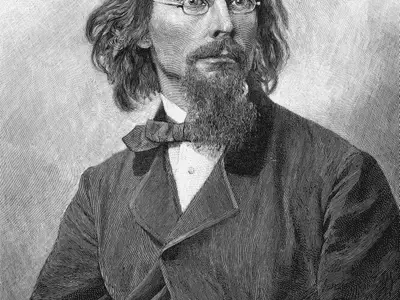

Born: 1825

Died: 1894

Summary of George Inness

Inness’s atmospheric, illustrative compositions are a significant contribution to nineteenth-century landscape painting in North America. It is also worth noting that Inness remained defiantly unaffected by the prevailing cultural trends of the time. When compared to the likes of Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church, Inness sought to explore and repurpose the European Romantic origins of his work. Proto-Impressionist Camille Corot’s soft brushwork and emphasis on light and tonal effects in his early works are reminiscent of the French Barbizon School. Turner-inspired boldness is evident in his later works. The tenacity with which Inness insisted on maintaining the uniqueness of his work made him an obstinate and unyielding figure in his field. For as long as there has been modern American painting, he has been a major influence.

Instead of breaking away from European Romanticism like the other early Hudson River School artists, George Inness stuck with it his entire life and became one of the Hudson River School’s most unique artists. Inness was a committed Europhile throughout his lifetime. As opposed to his contemporaries from the Hudson River School, George Inness travelled to Italy and rural France in search of new inspiration. In this regard, his work may be seen as a contribution to both European Naturalism and the classic American landscape of the 1950s and ’60s.

A cultural as well as a natural space is offered by George Inness’ paintings in his landscapes. In nineteenth-century American painting, large canvases were popular, in which all signs of human habitation were removed in order to evoke a wild, untamable setting. Humanity’s interaction with the landscapes they created was more important to Inness. In this way, his paintings represent a singularly optimistic view of social progress in the nineteenth century: they are monuments to an industrialization and urbanisation process that was felt to be able to bring about a new era of harmony between humanity and nature.

With studio work and an approach to landscape painting that combined elements of the real world with those invented by Inness, other artists like Frederic Edwin Church were unable to accept Inness’s vision of landscape painting as a hybrid. Aside from Church, who painted landscapes that could be considered both imaginative and artificial, Inness was the only Hudson River School artist to forego the plein air technique and devotion to nature that marked so many of his contemporaries’ landscapes.

Childhood

Born in 1825, George Inness grew up in the Hudson River valley near Newburgh. He was born to Clarissa and John Inness, a farmer and grocer, as the fifth of their thirteen children. In Newark, New Jersey, when he was just five, he was encouraged to read and learn about art by his parents, who were both artists. At 14, Inness began taking drawing lessons. His father had wanted him to become a grocer, but Inness had other plans. Despite the fact that his father was well-off and could afford to pay for his son’s education, his early training in the arts was cut short here. A child with epilepsy, Inness claimed that he had no formal education because of his illness. In fact, he is said to have been inspired by one of his father’s books on art, in particular the paintings of Claude Lorrain, which he would read and reread.

He began working as an engraver when he was just 16 years old, which was a common path for budding artists at the time. In New York, he worked for Sherman & Smith and N. Currier before returning to Chicago. Artworks by Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand had a profound impact on him, and he was inspired by their work. First real teacher John Jesse Barker met him in 1839, and he is thought to have been responsible for some of Inness’s colorist skills. His primary mentors, however, were the Old Masters: Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa are clearly visible in his compositions.

Early Life

François Gignoux, a French Hudson River School painter who specialised in snow scenes, approached Inness in 1843 and offered him a month of instruction. With the help of the group, Inness would become a close confidant of theirs. For all that he collaborated with the school and produced distinctly American landscape paintings, Inness’s goals and methods were markedly different from the school’s. Inspired by the great European traditions, Gignoux taught his young pupil to be Europhiles as well. He was hailed as a “young artist with good promise” at the National Academy of Design in 1844 when he exhibited there for the first time. He established a studio in New York in 1845.

George married Delia Miller in 1849, a woman whose identity has not been revealed. Inness remarried the following year to Elizabeth Abigail Hart, with whom he would have six children before she passed away.

Mid Life

Hudson River School painters like Frederic Edwin Church were travelling across the United States in the 1850s in search of new landscapes to paint, including the Andres. Contrast this with the European Romantic tradition of the Grand Tour, which Inness emulated by visiting Rome and Florence. While in Europe, Inness came across the works of Emanuel Swedenborg, the Swedish scientist and mystic who would have a lasting impact on Inness’ work and philosophy. Once, he said, “theology is the only thing except art that interests me.” —Inness. Contrary to fellow Swedenborgians William Page and Hiram Powers, Inness “does not express but hides” his religious beliefs in his art, according to Charles de Kay, an influential art critic of the time.

Controversial artist Inness is said to have cut short his 1851 trip to Italy after an altercation with a guard at an event held by the Pope in the Piazza of San Pietro. It is said that a French officer standing near Inness ordered him to take his hat off, to which the officer “rapped [the man in his army uniform’s epaulettes] over the head; whereupon there was an enormous disturbance among the soldiers…[they] took the little artist into custody and carried him to prison.” But it is possible that he was expelled from Italy after his release.

While in Paris in 1853, Inness became acquainted with the emerging French Realism movement, which included works by Gustave Courbet and others. “The fresh, loose brushwork, and overt emotional tenor of Barbizon paintings” were the influences that drew him to the work of Théodore Rousseau at the Paris Salon.

Inness’s nomadic lifestyle was in sync with his personal life, as he travelled the world. He was unstable, frequently ill, and prone to mood swings that were often depressive. In the past, he was known for kicking people out of his studio when they asked dumb questions. From the time he was a child and through his adulthood he moved away from the Hudson River Valley and the rest of North America, it symbolised a shift in his emotional state. The Hudson River School’s Jasper Francis Cropsey, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and Frederic Edwin Church were among the artists he grew distant from as he matured. While many of his contemporaries were heading in one direction, the mid-20th century curator and critic Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. was going the other way. The pioneering and nativist spirit of nineteenth-century American painting was out of sync with Inness’ fascination with European tradition, which was admittedly still influenced by it. “In Cikovsky’s view, “one of the worst things an American artist could do was to study the old masters.” It was the quickest and most effective way to lose one’s nationality.’ “For more information, please see the following link:

Many of the critics were of the same opinion. “Shallow affectations of that which is at best superficial to art—the accomplishment rather than the subject” was how one commentator characterised Inness’s early work in the art world. Reducing his enthusiasm for European art and instead painting what he saw in nature was a suggestion given to Inness. Inness wanted to show how man’s impact on the natural world contrasted with the grandeur and majesty of the American wilderness that surrounded him. “instead of minute fidelity to the facts of nature, he focused on the emotions the landscape evoked through the use of indefinite forms and suggestive colour,” curator Margi Conrad explains in her essay.

When Inness was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1853, he was only an associate member, whereas most of his Hudson River School contemporaries had already been granted full membership. When he returned to Europe in the mid-1850s, he was inspired by the paintings of Meindert Hobbema in the Rijksmuseum.

It was only in 1855 that Inness produced a series of paintings that were clearly influenced by the Barbizon School, but critics in the United States continued to be disappointed. When an artist with proven talent and a body of work this impressive prostitutes his ability to paint, it’s “scarcely credible.”

Inness moved to Medfield, Massachusetts, in an attempt to improve his health five years later. In addition to epilepsy, he was plagued by anxiety and depression because of his poor critical reception and financial insecurity. When he moved to Amsterdam, he began painting in the style of Dutch landscape painters and refined the Barbizon School’s influence. It is said that Inness and Rousseau shared the belief that an immaterial, even supernatural force generated all forms of life.

Late Life

Just as the first generation of the Hudson River School disbanded, Inness’s fortunes changed, but the Civil War seemed to change everything for Inness rather than the waning of the Hudson River flame. After failing the medical, he enlisted as an ardent abolitionist. Instead, he drummed up support for the cause by organising rallies, giving speeches, and attempting to persuade people to donate and volunteer. It appeared that Inness’ work gained favour as public opinion on the subject changed: people finally understood that it was intended to be interpretive rather than descriptive. Wartime tensions “created an emotional climate that was sensitive to his expressive style,” Cikovsky wrote. One critic called him “a man of unquestionable genius” by the end of the 1870s, and others began to see Inness in a new light.

Art Nouveau designer Louis Comfort Tiffany and landscape painter Carleton Wiggins were both students of Inness in 1863. Inness and his wife Elizabeth were baptised in the Swedenborgian New Church in Brooklyn five years after they first joined the congregation.

In 1870, Inness returned to Europe for the second time in four years, and stayed there until 1875. Before relocating to Normandy in 1874, he lived in Rome and painted a number of landscapes. Although he was present at the first Paris exhibition of Impressionism, he said that the style was “sham” and that it was a “passing trend.” Boston became his new home after he returned to the United States.

Inness didn’t really start making money from his art until the last decade of his life. When he purchased an estate in Montclair, New Jersey, in December of that year he decided to settle there permanently. Up until the age of sixty, he was still producing a lot of work and travelling a lot. He travelled to the Adirondacks, Niagara Falls, Nantucket, Virginia, Georgia, Chicago, California, Montreal, and England over the course of the last ten years of his life. These trips were fueled by “the unbridled energy that fueled these trips,” Baxter Bell writes, citing the “many accounts of Inness at work in his studio, which often focus on his physical engagement.”

Inness had finally found happiness, but he was still plagued by dyspepsia and rheumatism, and he was unable to lead a normal life. Friends were also concerned about his bouts of depression; he was reported to have attempted suicide. When life seemed too dark to bear, he was found bleeding to death in his studio, according to an early biography. He had cut open an artery in his arm.

By the time he died, Inness had been hailed as “America’s greatest living landscape artist” by the public. With regard to the spiritual and philosophical foundations of his work, Baxter Bell referred to Inness as the “leading American artist-philosopher of his generation.

At the age of 69, Inness died of a heart attack on a trip to Scotland. After watching the sun set, he yelled, “Oh, my God! Oh, how beautiful!” before falling to the ground. After his death, his body was returned to the United States and buried at the National Academy of Design in Washington. It is said that “[w]hen [Innes’] paintings had for a long time epitomised American artistic understanding and sensibility,” according to Cikovsky. He had produced around 1,150 works of art, including watercolours, sketches, and paintings.

Inness was hailed as “the father of American landscape painting” at the time of his death. After his death, he left behind a son and son-in-law, George Inness Jr. and Jonathan Scott Hartley, both of whom became painters and sculptors in their own right.

George Inness, despite not being a modern artist in the conventional sense, generated a lot of attention and debate during his lifetime. Many people were disgusted by his landscape paintings, while others were moved to rapturous praise by them, according to art historian Andrew Butterfield. One reviewer in the New York Times in 1878 speculated that Inness might be insane because of his “diseased” and “perverted” paintings.

New York landscape painter Inness has been compared to the English Romantic painter J.M.W. Turner because of his expressionistic approach to depicting landscapes. On the contrary, Inness scorned Turner’s ground-breaking Slave Ship, describing it as “Most depraved painting ever created. It’s a waste of time.” When it came to his work, he shunned comparisons to other artists because he was fiercely independent both professionally and personally.

Critics only began to appreciate Inness’s impact on art in his later years, whether it was paving the way for Tonalism or aligning the interests of the French Impressionists – whom Inness, of course, despised – with the march of American Art. Joseph Decker and William Keith were both influenced by this combination of influences. African American artist Charles White was also a fan of Inness’ landscape paintings, which he studied at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Famous Art by George Inness

The Lackawanna Valley

1855

For the first president of the Delaware Lackawant to and Western Railroad, George Inness produced one of his earliest paintings. By combining pastoral and industrial elements, Inness’ composition was paid $75. Fields on the outskirts of Scranton, Pennsylvania, are cut through by the tracks of the expanding railroad. Before us are tree stumps cut down to make way for progress, as well as a reclining man who is watching the approaching train with interest. When asked to add more tracks than existed, exaggerate the prominence of the roundhouse, and paint the company logo on the train, Inness was irritated. The steam engine and its roundhouse are visible beyond the intersection of the two sets of tracks in the middle of the layout. Toward the horizon, a church’s steeple stands out in black, while the calming blues and purples of the Pennsylvanian hills can be seen in the distance.

The Delaware Water Gap

1857

Similar to The Lackawant to Valley, this work depicts the emergence of the steam train network in North America, but the locomotive’s prominence is far less prominent in this work. On the border between Pennsylvania and New Jersey, we can see the Delaware Water Gap. Tonalism is predicated on the darkening of the rocks and grasses in the foreground by the cloud cover above. Despite the fact that Inness would reject impressionism on a trip to France 13 years later, this work contains a delicate light study in the style of European pre-Impressionists like Corot. A rainbow emerges from the ground to the left of the canvas, while the Kittatinny Mountains are blanketed in a white and yellow drizzle. A raft of people is seen bobbing up the Delaware River as cows laze on the water’s flat surface. In the distance, a small dark train can be seen steaming out of the canvas. In the same way that man and nature work in harmony, so do man and technology.

Peace and Plenty

1865

To the middle of his career, Inness continued to defy the artistic norms promoted by the Hudson River School, as exemplified by this lush and expansive canvas. Inness, who prefers the pastoral to the grandiose, paints Peace and Plenty with soft brushstrokes of copper, gold, and green, ushering in the Tonalist movement with his careful use of colour and composition to suggest spiritual harmony. Workers are seen putting down their harvesting tools after a long day of work. They’ve worked hard, and their reward is a golden twilight filled with piled-high sheaves of wheat. Natural elements are brought together once more in this composition by Inness, who cleverly hides the sun’s setting glow behind a central tree. Painter Inness used rich pigments to amplify the tranquilly of this scene, which includes slow-moving riverbanks and distant homes, as well as blue and pink sky.

The Monk

1873

Typical of Inness’s spirituality, this is one of his more enigmatic and evocative works. In the fading light, a cloaked monk walks with his head bowed. His bowed spine and a single dab of white paint hint at his advancing years, which are clearly visible. Large black silhouetted pines tower over the figure as they walk through the olive trees of Albano, Inness’ favourite Italian city, in the darkness. Villa Barberini, a summer residence of the Pope, is the setting for this scene. As a result, religious and landscape art depicted it frequently.

Niagara

1889

Inness’s late-career stylistic departure is evident in this audacious piece. Even though he’s going back to the themes of the great American landscapists with his depiction of the Niagara Falls (1857), Inness chooses to express the noise and power of the falls through expressive paintwork and romantic colour effects rather than mesmerising hypernaturalism. The viewer is perched high above the American bank and has a clear view of the foreground, which is densely populated with shrubbery and people. This composition is dominated by blues and greens of cascading water, which crash loudly into the composition’s centre and dissipate into vaporous clouds of mist. On the top third of the composition, a dark stormy sky is depicted, but Inness depicts a towering chimney belching out purple smoke that blends into the grey black sky, contrary to a common Hudson River school device.

Sunset in the Woods

1891

Just three years before Inness’s death, this painting exemplifies the artist’s ongoing dedication to his own artistic vision. When it comes to conveying an emotional response to the piece, the dark, almost magical-seeming wood at nighttime is the most effective medium. The gloaming obscures much of the detail, making it impossible to see any human figures or animals. To the right, a beech tree stands out against the green forest floor, which runs horizontally across the canvas in yellow gold tones. Backlight is blocked out by an enormous rock formation. A green strip of light can be seen in the distance, with more illuminated trees in the background, to the right of this. The ethereal and ghostly silence pervades the scene.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Inness’s atmospheric, illustrative compositions are a significant contribution to nineteenth-century landscape painting in North America.

- It is also worth noting that Inness remained defiantly unaffected by the prevailing cultural trends of the time.

- When compared to the likes of Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church, Inness sought to explore and repurpose the European Romantic origins of his work.

- Proto-Impressionist Camille Corot’s soft brushwork and emphasis on light and tonal effects in his early works are reminiscent of the French Barbizon School.

- Turner-inspired boldness is evident in his later works.

- The tenacity with which Inness insisted on maintaining the uniqueness of his work made him an obstinate and unyielding figure in his field.

- For as long as there has been modern American painting, he has been a major influence.

- Instead of breaking away from European Romanticism like the other early Hudson River School artists, George Inness stuck with it his entire life and became one of the Hudson River School’s most unique artists.

- Inness was a committed Europhile throughout his lifetime.

- As opposed to his contemporaries from the Hudson River School, George Inness travelled to Italy and rural France in search of new inspiration.

- In this regard, his work may be seen as a contribution to both European Naturalism and the classic American landscape of the 1950s and ’60s.

- A cultural as well as a natural space is offered by George Inness’ paintings in his landscapes.

- In nineteenth-century American painting, large canvases were popular, in which all signs of human habitation were removed in order to evoke a wild, untamable setting.

- Humanity’s interaction with the landscapes they created was more important to Inness.

- In this way, his paintings represent a singularly optimistic view of social progress in the nineteenth century: they are monuments to an industrialization and urbanisation process that was felt to be able to bring about a new era of harmony between humanity and nature.

- With studio work and an approach to landscape painting that combined elements of the real world with those invented by Inness, other artists like Frederic Edwin Church were unable to accept Inness’s vision of landscape painting as a hybrid.

- Aside from Church, who painted landscapes that could be considered both imaginative and artificial, Inness was the only Hudson River School artist to forego the plein air technique and devotion to nature that marked so many of his contemporaries’ landscapes.