(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1832

Died: 1883

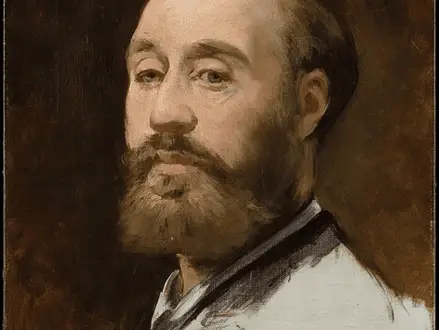

Summary of Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet was the most prominent and influential artist to follow poet Charles Baudelaire’s call for artists to become modern-day painters.

Manet was born into a wealthy family but led a bohemian lifestyle, and he was motivated to shock the French Salon public with his disdain for academic traditions and shockingly contemporary depictions of urban life.

He has long been linked with the Impressionists; he was undoubtedly a major influence on them, and he absorbed a great deal from them.

However, experts have now accepted that he drew inspiration from his French contemporaries’ Realism and Naturalism, as well as 17th-century Spanish art.

This dual interest in Old Masters and current Realism provided him with the necessary groundwork for his new approach.

Manet’s modernism stems mostly from his desire to modernise previous painting genres by adding new content or changing traditional aspects.

He did it with a keen awareness of both historical tradition and current events.

This was unquestionably the source of many of the scandals he sparked.

He is credited for popularising the alla prima painting style.

Rather than layering colours, Manet would start with the hue that most nearly resembled the ultimate effect he desired.

The Impressionists adopted the technique because it was well-suited to the challenges of portraying the effects of light and atmosphere while painting outside.

His so-called ‘sloppy’ painting style and schematic representation of volumes resulted in regions of “flatness” in his paintings.

This flatness may have evoked popular advertisements or the artifice of painting in the artist’s day, rather than its reality.

This characteristic is now regarded as the first example of “flatness” in modern art by critics.

Childhood

Édouard Manet grew raised in a Parisian upper-middle-class family. August, his father, was a committed and high-ranking civil worker, and Eugenie, his mother, was the daughter of a diplomat. Manet grew raised in a bourgeois household, both socially orthodox and financially wealthy, with his two younger brothers. He joined in a sketching class at The Rollin School at the age of thirteen, despite being a poor student at best.

Manet had a strong desire to be an artist since he was a child, but he consented to attend the Naval Academy to satisfy his father. He joined the Merchant Marine to obtain experience as a student pilot after failing the admission exam and sailed to Rio de Janeiro in 1849. He returned to France the next year with a portfolio of sketches and paintings from his travels, which he used to convince his father, who was dubious of Manet’s goals, of his talent and enthusiasm.

Early Life

Suzanne Leenhoff, Manet’s family’s piano teacher, had an affair with him in 1849. This encounter gave birth to Leon in 1852, who was adopted by Suzanne’s family and introduced to society as Suzanne’s younger brother and Manet’s godson to prevent controversy (from Manet’s aristocratic family). Manet proceeded to Italy the next year for both artistic and social reasons.

Manet’s father reluctantly permitted him to pursue his creative aspirations. In January 1850, Manet, true to his rebellious character, joined Thomas Couture’s workshop instead of attending the Ecole des Beaux-Arts to learn what he deemed obsolete styles. Despite the fact that Couture was an academic painter and a product of the Salon system, he encouraged his students to pursue their own personal expression rather than just adhering to the aesthetic standards of the day.

He spent six years studying under Couture before departing in 1856 to open his own workshop on rue Lavoisier. His capacity to open his own place (although in collaboration with painter Albert de Balleroy) was completely owing to his financial stability, which also allowed him to live his life and produce work in his own unique style.

It came easily to Manet to become a flâneur of Parisian life and to translate his views onto his canvases. He was also able to go across Holland, Germany, and Austria, as well as visit Italy on numerous times, thanks to his financial security. He met Edgar Degas and Henri Fantin-Latour, whom he would become friends with for the rest of his life.

Mid Life

Manet was a progressive thinker who thought that art should reflect current life rather than history or mythology. He was friends with poet Charles Baudelaire and artist Gustave Courbet. This was a turbulent creative transition that pitted the Salon’s status quo against avant-garde artists who were victimised by a conservative audience and harsh critics. Manet was at the centre of numerous of these debates, and his paintings were rejected by the Salon of 1863. After Manet and others objected, the Emperor relented and placed all of the rejected pieces in the secondary Salon des Refusés, allowing the public to view what had been considered unacceptable.

For a variety of reasons, the startling Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (1863) received the most condemnation. Viewers didn’t get the Renaissance allusions, but they did get the blatant and realistically portrayed nudity of a lady – most likely a prostitute – gazing at them from the painting. Critics said the picture was “vulgar,” “immodest,” and “unartistic,” which upset Manet and possibly contributed to his melancholy.

Manet’s ego and personal reputation would have been harmed by his inclusion at the Salon des Refusés. His rebellious inclinations led him to desire to modify the exclusive structure that the institutions – the Salon and Ecole des Beaux Arts – functioned under, but he did not want them to be abolished. Manet was firmly rooted in his upper-middle-class upbringing, and he aspired to succeed at the Salon – but only on his terms, not theirs. As a consequence, an unknowing revolutionary and, possibly, the first modern artist was born.

The following year, when he released Olympia (1863), which showed another nude of his favourite model, Victorine Meurent, he sparked even more controversy. While painting her complete body for the world to see, Manet claimed to perceive the truth in her face. When shown in the 1865 Salon, this was deemed too aggressive and unpleasant by the Parisian audience. “They are raining insults upon me, I’ve never been led such a dance.” he wrote to his close friend Baudelaire.

Manet and Suzanne married to legalise their relationship when Manet’s father died in 1862, however their son Leon may never have learned his actual origin. Manet’s mother had most likely assisted the two in keeping the secret from Manet’s father, who would not have accepted the humiliation of having an illegitimate child in the family. There has also been conjecture that Leon is the son of Manet’s father, although this is quite doubtful.

In 1864, Manet moved to rue des Batignolles, and in 1866, he began holding court at the Café Guerbois every Thursday with artists such as Henri Fantin-Latour, Edgar Degas, Emile Zola, Nadar, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, and, by 1868, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley. The “the Batignolles Group” gatherings brought together a diverse range of personalities, attitudes, and social classes, all of whom came together as independent-minded, avant-garde artists to establish the principles of their new artistic approaches.

The Fifer (1866) and The Tragic Actor (1866) were rejected by the Salon of 1866. (1866). Manet responded by holding a public display in his studio. Zola was sacked from L’Evenement for writing an essay about Manet in support of this avant-garde approach. Following his exclusion from the Paris Exposition Universelle the following year, Manet chose not to submit anything to the Salon and instead put up a tent beside Courbet’s to display his work outside the Exposition, where he was roundly chastised.

Manet was fascinated in Spanish culture after painting a company of Spanish entertainers in 1861, and after visiting Spain in 1865, he was influenced by the works of Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya. This was reflected in his writing style as well as his subject matter. Manet, an ardent Republican, was dissatisfied with Napoleon III’s administration. In the picture The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867), he linked the French government in Maximilian’s sad end in Mexico, a compositional homage to Goya. This art was deemed too politically charged to be displayed, therefore it was prohibited.

In 1868, Henri Fantin-Latour introduced Manet to the Morisot sisters, which was a pivotal encounter. Manet’s relationship with Berthe Morisot, a painter, was tumultuous at best. She became his student, and he admired her as a painter, using her as a model on several occasions. A real affair was impossible despite a multi-year mutual desire (both were from proper families, Manet was married, and Morisot only saw him with a chaperone). When Manet painted and also tutored the young Eva Gonzales on one occasion, Morisot was terribly wounded.

Morisot eventually married Manet’s younger brother Eugene to prevent any household strife (who was certainly not the charismatic star that Manet was). This completely terminated their personal connection, since Morisot never sat for him again, but she remained Manet’s most ardent supporter.

Manet’s importance to the contemporary art world is seen in Fantin-A Latour’s Studio at Batignolles (1870), which portrays a meeting of Monet, Zola, Bazille, and Renoir, among others, all admiring Manet as he paints in his own studio. While several of his friends, including Monet, fled to London to avoid the Franco-Prussian War, Manet enlisted in the National Guard. Manet was compelled to stay out of Paris for the following few years due to political circumstances, returning only temporarily during the Versailles persecution. In 1872, he was compelled to abandon his wrecked studio and establish himself on the rue de Saint-Petersbourg.

In 1875, Manet enraged the Salon once more with his contribution Argenteuil (1874), which had a brighter palette and Monet’s Impressionism. Manet sent the Salon Argentueil, which was essentially a manifesto of the new style, aimed to individuals who had not seen the group’s key show in 1874.

In response to the Salon’s rejection of some of his paintings at 1876, Manet held another show in his studio, which drew over 4,000 people. Despite the fact that many in the press felt the Salon’s rejection was unjust, he continued to be shunned, eventually receiving a refusal in 1877.

Manet did not display anything in 1878 because he refused to submit to the Salon or host his own exhibition. Instead, he shifted studios. That same year, his health began to interfere with his everyday activities.

Late Life

Following a period away from Paris to help his failing health, Manet was given a 2nd place medal in the Salon of 1880, earning him a pass from future competition and the opportunity to become a permanent exhibitor at all future Salons. In 1881, Manet received the Legion of Honor, among other honours. Manet continued his life as a flâneur, documenting modern developments in the streets of Paris and the lives of its citizens. Café concerts were a powerful symbol of these shifts, providing a space where men and women from all walks of life could interact while enjoying companionship, beverages, and entertainment.

Even from his sickbed, Manet continued to create portraits of women, still lifes, landscapes, and flowers (he was unable to visit his studio in the last months of his life). Manet had a horrific end after succumbing to a neurological ailment – most likely tertiary syphilis – after being confined to a wheelchair by gangrene and even losing his limb. He was just 51 years old when he died. He bequeathed his fortune to Suzanne in his will and required her to give everything to Leon upon her death, thereby confirming Leon as Manet’s son and heir.

Manet’s widow and friends fought hard after his death to preserve his memory and legacy, with remarkable sales of his paintings, government acquisitions, and the publication of many biographies. Many art historians consider Manet to be the founder of modern art, and his impact on modernism is undeniable. While his work life was marked by grandeur and scandal, his yearning for respectability eventually ruled his personal life. Despite his brief career, which spanned just over two decades, his work may be found in most major worldwide museums and galleries.

Edmond de Goncourt, a 19th-century writer, summed him up well. “We have the death of oil painting, that is, of painting with a beautiful, amber, crystalline transparency, of which Rubens’ Woman in a Straw Hat is the pinnacle, with Manet, whose methods are stolen from Goya, with Manet and all the artists who have followed him. Opaque painting, matt painting, chalky painting, and painting with all the qualities of furniture paint are now available. From Raffaelli to the last tiny Impressionist dauber, everyone is painting it this way.”

Famous Art by Édouard Manet

Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe

1863

It’s easy to see why this canvas startled bourgeois patrons and the Emperor himself as the main discussion point of the Salon des Refusés in 1863. Manet’s composition is influenced by Renaissance artist Giorgione and Raimondi’s etching of Raphael’s Judgment of Paris, but these inspirations are shattered by his lack of perspective and use of artificial light sources. The biggest popular indignation, however, was caused by the sight of an unidealized female nude, casually engaging with two elegantly dressed males.

Olympia

1863

Manet’s Olympia, which depicts a lower-class prostitute, confronts the bourgeois observer with a concealed but well-known reality. It startled the audience at the 1865 Salon because it was purposefully offensive. The references to Titan’s Venus of Urbino (1538) and Goya’s Maja Desnuda (1799-1800) fit comfortably within the classic “boudoir” genre, but they end in a fairly informal and unique picture of a lady unafraid of her body. Olympia is considered to be a visual representation of portions from Charles Baudelaire’s famous collection of poetry, Les Fleurs du Mal (1857).

A Bar at the Folies-Bergere

1882

Manet’s final masterwork is probably this melancholy café scene. The Folies-Bergere was a stylish and varied crowd’s favourite café concert. Behind the focal figure, the sorrowful bar lady, the vibrant bar scene is mirrored in the mirror. Her lovely, weary eyes avoid making eye contact with the spectator, who also serves as the client in this moment. The distorted perspective from the mirror image has gotten a lot of attention, although it was clearly part of Manet’s concern in artifice and reality.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Édouard Manet was the most prominent and influential artist to follow poet Charles Baudelaire’s call for artists to become modern-day painters.

- Manet was born into a wealthy family but led a bohemian lifestyle, and he was motivated to shock the French Salon public with his disdain for academic traditions and shockingly contemporary depictions of urban life.

- He has long been linked with the Impressionists; he was undoubtedly a major influence on them, and he absorbed a great deal from them.

- However, experts have now accepted that he drew inspiration from his French contemporaries’ Realism and Naturalism, as well as 17th-century Spanish art.

- This dual interest in Old Masters and current Realism provided him with the necessary groundwork for his new approach.

- Manet’s modernism stems mostly from his desire to modernise previous painting genres by adding new content or changing traditional aspects.

- He did it with a keen awareness of both historical tradition and current events.

- He is credited for popularising the alla prima painting style.

- Rather than layering colours, Manet would start with the hue that most nearly resembled the ultimate effect he desired.

- This flatness may have evoked popular advertisements or the artifice of painting in the artist’s day, rather than its reality.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.