(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1894

Died: 1954

Summary of Claude Cahun

It’s impossible not to be taken aback by Claude Cahun’s vivid self-portraits.

Claude Cahun was born in France, but grew up on Jersey with his longtime girlfriend, Marcel Moore. During their adolescence, both Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe chose gender-neutral pen names. Moore, although frequently invisible, was constantly present – generally taking the images and also creating collages – and in this sense was as much artist collaborator as Cahun’s personal support. It’s a “search” in Cahun’s words, and it’s a study of the self that is both relentless and unnerving. Cahun’s journey from circus performer to Buddhist monk is a continuous conversation with a variety of different perspectives. Unfortunately, much of Cahun’s work was destroyed during his time in prison for resisting the Nazis, in keeping with his fragmentary outlook. What remains bares interesting relation to the title of Cahun’s diaristic publication Aveux Non Avenus, translated as Disavowels, which enigmatically suggests that for all that is shown and given, much is still concealed or has been lost.

Themes of melancholy, futility, and uncertainty run deep through Cahun’s oeuvre. All of Cahun’s images and texts are part of a larger and yet unfinished whole, which is the point of his work. For the first time in a long time, Cahun reveals the rawness and pain of not knowing.

“Who Am I?” is the recurring theme of Nadja (1928), and Moore collaborated with Breton on collages depicting symmetry and prismatic vision, just as the book’s images. In general, Cahun shares an interest in specific motifs such as hair, hands, and animal familiars with other female Surrealists, and similarly uses techniques of doubling and reflection to bring into question established concepts of gender and identity.

Francesca Woodman, Cindy Sherman, and Gillian Wearing can all be found in Cahun’s work. Drawing on Joan Rivière’s landmark thesis on women who use “womanliness as disguise,” Sherman and Wearing both go on to investigate the idea of many “masked” identities, influenced by Cahun’s plays (1929). Cahun’s more recent outdoor images, on the other hand, were the inspiration for Woodman. Both artists are entwined in seaweed, surrounded by plants, and submerged in water as they masterfully mix eros and thanatos in the grandeur of nature.

Cahun has become a reclusive character because of the artist’s obscurity. Cahun was an intense loner in character, yet he was also inseparable from Moore. After moving from Paris to Jersey in 1937, the pair became awkward, alienated, and unavailable as a result of their isolation. As a result, the whole known output of Cahun was reduced to a relatively small number of works, further increasing the mystery. As though they were clues to a far larger treasure hunt, the original works that remain are relatively modest.

Biography of Claude Cahun

Childhood

The daughter of a middle-class French Jewish family, Lucy Schwob became Claude Cahun in 1894. The artist and writer Lucy Schwob changed her name to Claude Cahun later in life in order to be more gender neutral. A well-known Symbolist author was Lucy’s uncle Marcel, who had a younger brother, George. A well-known Parisian figure, Marcel Schwob was close friends with Oscar Wilde. When Cahun was just a youngster, his grandfather David Leon Cahun was an important player in the Orientalist movement, therefore the artist was already steeped in a creative and intellectual milieu.

Acute mental illness in Cahun’s mother led to her being institutionalised and Cahun being raised mostly by their blind grandma. When his mother became sick and an anti-semitic event occurred at school in France, Cahun was sent to boarding school in Surrey, England. At the age of 15, Cahun had anorexia and suicidal tendencies, just like their mother. Fortunately, Cahun met love and his eventual lifetime spouse Suzanne Malherbe at this time as well. After this “thunderbolt encounter,” Cahun’s life and work were forever changed, and their friendship had a major influence. The father of Malherbe became the stepfather of Cahun’s mother when he remarried. Despite this, Cahun and Malherbe became lovers and travelled to Paris in 1919, when Dada was at its peak, when they acquired the gender-neutral aliases Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore.

Early Life

Although Cahun and Moore’s attempt at gender agnosticism was widely derided, the pair grew to identify with the small group of avant-garde individuals in Paris who were also experimenting with gender at the time. Rrose Selavy, Marcel Duchamp’s female alter-ego, first introduced in 1920. It wasn’t about changing gender for Cahun and Moore, but about breaking free of these antagonistic manufactured relationships.

Cahun attended the Sorbonne in Paris to study literature and philosophy. Cahun and Moore began inviting avant-garde writers and artists to their home salons and parties from 1922. He had been fascinated in photography and self-portraiture since the age of 12, but he didn’t start experimenting with the medium until the 1920s when he created some of his most memorable and iconic photos. Although he wasn’t a member of the Surrealist movement, Cahun found himself on the outskirts. Pierre Albert-Birot, the director of Le Plateau, the experimental theatre where Cahun acted and Moore designed stage sets and costumes, became familiar to Cahun and Moore. In the 1920s, in addition to photography, Cahun concentrated on writing. The novel Heroines was released in 1925, and Aveux Non Avenus (1930) was an important collection of texts and photo-collages – in a restricted edition of 500 copies.

Mid Life

While working with Moore in the 1930s, Cahun developed a greater interest in politics, and they both protested against fascism throughout Europe. To meet Andre Breton, one of the founders of the Surrealist movement, Cahun joined the “Association des Ecrivains et Artistes Revolutionnaires” in Paris in 1932. Cahun gave Breton a copy of Aveux Non Avenus when they first met, and the experimental wording impressed him. Their friendship became stronger over time, and Breton once referred to Cahun as “one of our time’s most intriguing spirits.” As a member of the Surrealist movement, Cahun’s work with Moore was also admired by the likes of René Crevel and Robert Desnos, as well as poet and painter Henri Michaux, with whom Cahun made hospital visits. Meetings with the Surrealist group became more frequent, and Cahun began to display his work alongside them, notably at key Surrealist exhibits in London and Paris, which took place the next year (in 1936).

Surrealists split from the French Communist Party in 1935, and Cahun remained on the side of Breton and Bataille as they tried to use art to halt the spread of the Second World War. For Cahun’s part, Breton encouraged him to write a rejoinder to Louis Aragon, who had abandoned Surrealism in favour of Communism. As a response to Aragon’s views, Cahun wrote “The Bets are Open,” a text that uses poetry rather than propaganda to disseminate its point.

In 1937, Cahun and Moore relocated to Jersey, a British island between England and France, where they lived in a mansion called La Rocquaise. Even though Cahun and Moore continued to produce art (both photographic and textual) beyond this moment, their involvement in the Surrealist movement practically came to an end. Cahun and Moore began to use their original names again and became known as “les mesdames” to the other local people of Jersey and earned a reputation for unusual actions, such as taking their cat for a walk on a lead and wearing pants.

Late Life

The Nazis seized Jersey in 1940, the closest they ever came to mainland British soil, as the pair watched the expansion of Nazism across Europe. They opted not to run, but rather to stay and participate in the resistance, creating anti-Nazi propaganda. Because they were two older women, they were not first considered suspects of espionage. In order to undermine the morale of the German troops and incite them to desert, they would sneak their homemade flyers into the pockets of the latter. Using the phrase “militant surrealist activity,” Cahun described their resistance as an extension of the “indirect action” Cahun supported as member of the Surrealist group. Resistance by Cahun and Moore, according to certain art historians like Lizzie Thynne, should be understood as a continuation of their radical artistic practises.

They were sentenced to death in July 1944 after being caught on charges of inciting the troops to revolt by listening to the BBC. For nearly a year, they were held in separate cells, finally being released when the island was liberated in May 1945. On their return, they discovered that the Nazis had demolished much of their artwork.

Cahun received the Medal of French Gratitude in 1951 as a result of his role in the resistance. Cahun died in 1954 following a long battle with illness, which may have been exacerbated by his time in prison.

As a result of his many personae and odd personal life, Cahun has become an important character in the development of contemporary art. It is Cahun’s gender-shifting self-presentation and non-heterosexual relationship that made Cahun essential to both gay activists and feminists. As a result, the use of photography in self-portraiture by Cahun marks the beginnings of a new trend among non-male artists, as well. Cahun’s technique draws into an artist’s dual urge to examine questions of gender, sexuality, and power. As an example, Gillian Wearing’s Me as Cahun Holding a Mask of My Face is a direct answer to Cahun’s work (2012). Wearing recreates Cahun’s renowned self-portrait from the I Am In Training Don’t Kiss Me series in this photo self-portrait (c.1927). Wearing photos of herself in a mask of Cahun’s face, while holding a mask that is an exact copy of her own features.

Cahun’s work has also had an impact on renowned personalities like David Bowie, who have fought against gender stereotypes. An exhibition of Cahun’s art was organised by Bowie in New York City in 2007. About Cahun, he said: “You could describe her as provocative or as a surrealist Man Ray dressed as a woman. In the nicest possible sense, I find this work insane. She hasn’t received the attention she deserves outside of France and the United Kingdom as a founding member, friend, and worker of the original Surrealist movement.”

Famous Art by Claude Cahun

Self Portrait as a Young Girl

1945

One of Cahun’s first known self-portraits, this image captures the artist’s strong and penetrating gaze. The disembodied head of the artist suggests an imbalance as if the head is abnormally heavy and the body is unnecessary. Art historian Sarah Howgate, a specialist in the works of Claude Cahun, believes that “she seems like an invalid in a hospital bed” and proposes that this may be a visual reference to Cahun and Cahun’s mother’s depressive periods. The woman appears to be dead and at a morgue, thus this is a viable avenue of investigation. However, Cahun’s eyes are wide open and clearly alive despite his seeming death, maybe because he is burdened by an inner knowledge of life’s darker and more hidden parts.

Self Portrait, Head Between Hands

1920

Lucy Schwob’s identity as a little girl has been subsumed under the gender-neutral character of Claude Cahun in this arresting portrait. Shaved heads have taken the place of women’s long locks, eradicating the romantic notion that flowing locks are a sign of femininity. It is one of a handful of bald-headed portraits created in the same year An existentialist image of The Scream by Edvard Munch appears in this painting, while another shows Cahun in a suit and another shows him sitting cross-legged on the ground in a monk-like stance. All three images depict a concept of gender-neutrality that reflects Cahun’s personal experience at the time, developed while he was involved in the Parisian lesbian avant-garde community. It’s worth noting that in postwar Europe as a whole, gender conceptions are being questioned. Frida Kahlo, for example, wore a man’s costume in family photos in the 1920s, and later painted Self Portrait with Cropped Hair in 1940, in which she posed with her hair cropped.

Photograph from the series “I am in training don’t kiss me”

1927

In contrast to earlier works, Cahun displays a clearly created identity in this and other images made in the latter years of the 1920s employing props, highly exaggerated attire, and make-up. A series of photos depicts Cahun as a feminised strongman and he executes various stances as such in the photographs. Converging masculine and feminine stereotypes, Cahun uses this persona to adorn the flat costume shirt with fake nipples, and even the customary weightlifter handlebar moustache has been shifted onto Cahum’s hair. Cahun’s chest said, “I am in training, don’t kiss me,” with coquettishly pursed lips. With a flirtatious and tempting glance, it mocks the observer for being drawn to something that is obviously not on offer. With the strongman series’ theatrical nature, it highlights the intriguing gap between the two extremes of gender identity. It wasn’t long after this photograph was shot in 1929 that Cahun published essays in magazines outlining contentious views about a third gender, one that included masculine and feminine qualities yet existed as neither one nor the other.

Claude Cahun Plate no.1 from Aveux non Avenus (1930)

1930

The first illustration of Cahun’s autobiographical narrative, Aveux not Avenus, is depicted here (translated as “Disavowals”). An eye, globe, and magnifying glass or hand mirror are all depicted in this image. The pinnacle has a double-headed bird perched atop a pair of isolated lips formed by the severance of one pair of hands. A dark, star-studded sky is topped with a probable breast, a shell, and a plethora of folded fabric. There is a celestial and dreamlike evocativeness to the whole effect. It shows Cahun at a time when he was most interested in Surrealism’s concepts and most receptive to external influences. In fact, the photomontage technique is a popular Surrealist method. While residing in Paris, Cahun may have come across this piece by Hannah Hoch, Max Ernst, and Hans Arp, pioneers of the technique. It is somewhat uncommon for Ernst and Arp to utilise birds in their early collages, but it is more common for Hoch to employ eyes and, like Cahun (in other photomontages), transform a large collection into a flower’s petals. Despite the fact that majority of the re-appropriated pictures were taken by Cahun, Marcel Moore may have been responsible for putting them together into a cohesive composite work. To make it replicable in Disavowels, the collage/photomontage was photographed after it was finished.

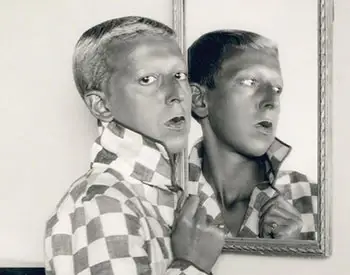

Untitled (Self-Portrait with Mirror)

Unknown Date

A mirrored-reflection doubles Cahun’s boldness and androgynous appearance. Rich in textures and tones, the image is bursting with life thanks to the checkerboard jacket, highlighted hair, and smooth, sun-kissed skin. Women’s vanity has been highlighted in art for centuries through the addition of mirrors, which have been utilised to show the subject from two different angles. The’real’ Cahun, on the other hand, glances away from the mirror and directly into the camera’s lens. Cahun defies the stereotype of a docile woman absorbed by her own adoration. The viewer is confronted with elements of deliberation, exploration, and self-assurance in this work. There is no vanity at work here. “‘refusing to be imprisoned in her own glass, Cahun resolved to live the fictional life within the carefully guarded walls of her own introverted mental theatre,” says art historian Shelley Rice. A mirror image of Cahun, the ‘false’ Cahun, appears to be looking out of the frame, maybe feeling more at ease in a fantasy-world than in the real one.

Self-Portrait with Masked Face and Graveyard

1947

In this relatively late work, Cahun investigates a cemetery because he is fascinated by the ongoing oscillation between the impulse to live and the instinct to die. Cahun would be buried in the same cemetery seven years later, when he died at the age of 60. This photograph was taken before Cahun had been imprisoned for one year in a Nazi camp, only to be released in 1945 with lasting effects on his health. While imprisoned, Cahun was certainly haunted by thoughts of death, especially as his health deteriorated and he became more and more isolated. His features are hardly discernible through the fabric-like mask that covers his face. As in Cahun’s earlier self-portrait Self Portrait, Head Between Hands (1920), his hands are elevated, holding the mask on either side, evoking the prior stance.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- It’s impossible not to be taken aback by Claude Cahun’s vivid self-portraits.

- Claude Cahun was born in France, but grew up on Jersey with his longtime girlfriend, Marcel Moore.

- During their adolescence, both Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe chose gender-neutral pen names.

- Moore, although frequently invisible, was constantly present – generally taking the images and also creating collages – and in this sense was as much artist collaborator as Cahun’s personal support.

- It’s a “search” in Cahun’s words, and it’s a study of the self that is both relentless and unnerving.

- Cahun’s journey from circus performer to Buddhist monk is a continuous conversation with a variety of different perspectives.

- Unfortunately, much of Cahun’s work was destroyed during his time in prison for resisting the Nazis, in keeping with his fragmentary outlook.

- What remains bares interesting relation to the title of Cahun’s diaristic publication Aveux Non Avenus, translated as Disavowels, which enigmatically suggests that for all that is shown and given, much is still concealed or has been lost.

- Themes of melancholy, futility, and uncertainty run deep through Cahun’s oeuvre.

- All of Cahun’s images and texts are part of a larger and yet unfinished whole, which is the point of his work.

- For the first time in a long time, Cahun reveals the rawness and pain of not knowing.

- “Who Am I?”

- is the recurring theme of Nadja (1928), and Moore collaborated with Breton on collages depicting symmetry and prismatic vision, just as the book’s images.

- In general, Cahun shares an interest in specific motifs such as hair, hands, and animal familiars with other female Surrealists, and similarly uses techniques of doubling and reflection to bring into question established concepts of gender and identity.

- Francesca Woodman, Cindy Sherman, and Gillian Wearing can all be found in Cahun’s work.

- Drawing on Joan Rivière’s landmark thesis on women who use “womanliness as disguise,” Sherman and Wearing both go on to investigate the idea of many “masked” identities, influenced by Cahun’s plays (1929).

- Cahun has become a reclusive character because of the artist’s obscurity.

- Cahun was an intense loner in character, yet he was also inseparable from Moore.

- After moving from Paris to Jersey in 1937, the pair became awkward, alienated, and unavailable as a result of their isolation.

- As a result, the whole known output of Cahun was reduced to a relatively small number of works, further increasing the mystery.

- As though they were clues to a far larger treasure hunt, the original works that remain are relatively modest.

- Biography of Claude Cahun ChildhoodThe daughter of a middle-class French Jewish family, Lucy Schwob became Claude Cahun in 1894.

- The artist and writer Lucy Schwob changed her name to Claude Cahun later in life in order to be more gender neutral.

- A well-known Symbolist author was Lucy’s uncle Marcel, who had a younger brother, George.

- A well-known Parisian figure, Marcel Schwob was close friends with Oscar Wilde.

- When Cahun was just a youngster, his grandfather David Leon Cahun was an important player in the Orientalist movement, therefore the artist was already steeped in a creative and intellectual milieu.

- Acute mental illness in Cahun’s mother led to her being institutionalised and Cahun being raised mostly by their blind grandma.

- When his mother became sick and an anti-semitic event occurred at school in France, Cahun was sent to boarding school in Surrey, England.

- At the age of 15, Cahun had anorexia and suicidal tendencies, just like their mother.

- Fortunately, Cahun met love and his eventual lifetime spouse Suzanne Malherbe at this time as well.

- After this “thunderbolt encounter,” Cahun’s life and work were forever changed, and their friendship had a major influence.

- The father of Malherbe became the stepfather of Cahun’s mother when he remarried.

- Despite this, Cahun and Malherbe became lovers and travelled to Paris in 1919, when Dada was at its peak, when they acquired the gender-neutral aliases Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore.

- Early LifeAlthough Cahun and Moore’s attempt at gender agnosticism was widely derided, the pair grew to identify with the small group of avant-garde individuals in Paris who were also experimenting with gender at the time.

- Cahun attended the Sorbonne in Paris to study literature and philosophy.

- Cahun and Moore began inviting avant-garde writers and artists to their home salons and parties from 1922.

- He had been fascinated in photography and self-portraiture since the age of 12, but he didn’t start experimenting with the medium until the 1920s when he created some of his most memorable and iconic photos.

- Although he wasn’t a member of the Surrealist movement, Cahun found himself on the outskirts.

- Pierre Albert-Birot, the director of Le Plateau, the experimental theatre where Cahun acted and Moore designed stage sets and costumes, became familiar to Cahun and Moore.

- In the 1920s, in addition to photography, Cahun concentrated on writing.

- The novel Heroines was released in 1925, and Aveux Non Avenus (1930) was an important collection of texts and photo-collages – in a restricted edition of 500 copies.

- Mid LifeWhile working with Moore in the 1930s, Cahun developed a greater interest in politics, and they both protested against fascism throughout Europe.

- To meet Andre Breton, one of the founders of the Surrealist movement, Cahun joined the “Association des Ecrivains et Artistes Revolutionnaires” in Paris in 1932.

- Cahun gave Breton a copy of Aveux Non Avenus when they first met, and the experimental wording impressed him.

- Their friendship became stronger over time, and Breton once referred to Cahun as “one of our time’s most intriguing spirits.”

- As a member of the Surrealist movement, Cahun’s work with Moore was also admired by the likes of René Crevel and Robert Desnos, as well as poet and painter Henri Michaux, with whom Cahun made hospital visits.

- Meetings with the Surrealist group became more frequent, and Cahun began to display his work alongside them, notably at key Surrealist exhibits in London and Paris, which took place the next year (in 1936).Surrealists split from the French Communist Party in 1935, and Cahun remained on the side of Breton and Bataille as they tried to use art to halt the spread of the Second World War.

- For Cahun’s part, Breton encouraged him to write a rejoinder to Louis Aragon, who had abandoned Surrealism in favour of Communism.

- In 1937, Cahun and Moore relocated to Jersey, a British island between England and France, where they lived in a mansion called La Rocquaise.

- Even though Cahun and Moore continued to produce art (both photographic and textual) beyond this moment, their involvement in the Surrealist movement practically came to an end.

- Cahun and Moore began to use their original names again and became known as “les mesdames” to the other local people of Jersey and earned a reputation for unusual actions, such as taking their cat for a walk on a lead and wearing pants.

- Late LifeThe Nazis seized Jersey in 1940, the closest they ever came to mainland British soil, as the pair watched the expansion of Nazism across Europe.

- They opted not to run, but rather to stay and participate in the resistance, creating anti-Nazi propaganda.

- Because they were two older women, they were not first considered suspects of espionage.

- In order to undermine the morale of the German troops and incite them to desert, they would sneak their homemade flyers into the pockets of the latter.

- Using the phrase “militant surrealist activity,” Cahun described their resistance as an extension of the “indirect action” Cahun supported as member of the Surrealist group.

- Resistance by Cahun and Moore, according to certain art historians like Lizzie Thynne, should be understood as a continuation of their radical artistic practises.

- They were sentenced to death in July 1944 after being caught on charges of inciting the troops to revolt by listening to the BBC.

- For nearly a year, they were held in separate cells, finally being released when the island was liberated in May 1945.

- On their return, they discovered that the Nazis had demolished much of their artwork.

- Cahun received the Medal of French Gratitude in 1951 as a result of his role in the resistance.

- Cahun died in 1954 following a long battle with illness, which may have been exacerbated by his time in prison.

- As a result of his many personae and odd personal life, Cahun has become an important character in the development of contemporary art.

- It is Cahun’s gender-shifting self-presentation and non-heterosexual relationship that made Cahun essential to both gay activists and feminists.

- As a result, the use of photography in self-portraiture by Cahun marks the beginnings of a new trend among non-male artists, as well.

- Cahun’s technique draws into an artist’s dual urge to examine questions of gender, sexuality, and power.

- As an example, Gillian Wearing’s Me as Cahun Holding a Mask of My Face is a direct answer to Cahun’s work (2012).

- Wearing recreates Cahun’s renowned self-portrait from the I Am In Training Don’t Kiss Me series in this photo self-portrait (c.1927).

- Wearing photos of herself in a mask of Cahun’s face, while holding a mask that is an exact copy of her own features.

- Cahun’s work has also had an impact on renowned personalities like David Bowie, who have fought against gender stereotypes.

- An exhibition of Cahun’s art was organised by Bowie in New York City in 2007.

- About Cahun, he said: “You could describe her as provocative or as a surrealist Man Ray dressed as a woman.

- In the nicest possible sense, I find this work insane.

- She hasn’t received the attention she deserves outside of France and the United Kingdom as a founding member, friend, and worker of the original Surrealist movement.”

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.