(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1940

Died: 2021

Summary of Chuck Close

Chuck Close is most known for reviving the art of portrait painting from the late 1960s to the present day, during which time photography was challenging painting’s prior supremacy in this field and slowly earning critical acclaim as an independent creative medium. Close arose from the 1970s painting movement of Photorealism, also known as Super-Realism, but went on to explore how methodical, system-driven portrait painting based on photography’s underlying processes (rather than its superficial visual appearances) could suggest a wide range of artistic and philosophical concepts. Close’s personal struggles with dyslexia and, as a result, partial paralysis, have also suggested real-life parallels to his professional discipline as if his methodical and yet intuitive painting methods are inextricably linked to his daily reckoning with the body’s own vulnerable, material condition.

Close quickly moved to portraiture after attaining the glossy, mirror-like “look” of the image in 1970s photorealist painting, suggesting it as a manner of examining disturbing elements of how self-identification is always a composite and highly manufactured, if not ultimately conflicting fabrication. The camera’s analytical, serial approach to any given topic is a conceptual parallel to Close’s reliance on the grid as a metaphor for his analytical methods, which indicate that the “whole” is rarely more (or less) than the sum of its parts. Every bright, street-smart Polaroid is as much a time-based and fragmented gesture as any more painstaking brushstroke in the cloistered studio. Close has experimented with a variety of mediums, including oil and acrylic painting, photography, mezzotint printing, and others. Close boldly shifts from one to the other, implying that his conceptual objectives are eternal, yet his means or materials are infinitely interchangeable. This is one of the reasons why Close’s portrait painting has stayed unexpectedly “contemporary,” for over four decades, even while the wider trend of Photorealism, his first artistic idiom, has faded into history. Close’s slow, accumulative processes, which employ a variety of abstract colour applications in the service of creating “realistic,” or illusory portraits, have recently found application in the art of modern tapestry, thanks to a highly illusionistic, computer-aided method of industrial weaving that Close favours for its ability to suggest the hyper-real appearance of 19th-century glass photographs (daguerreotypes).

Childhood

Leslie and Mildred Close, a couple who favoured creative activities, gave birth to Charles Thomas Close at home. Charles’ first easel was made by Leslie Close, a jack-of-all-trades with a knack for workmanship. His mother was a trained pianist who, due to financial restrictions, was unable to continue a musical career. Mildred pushed Charles to participate in a variety of extracurricular activities during his school years and hired a local tutor to offer him individual painting classes, determined to provide him with possibilities she had never had. Because of his dyslexia, Charles struggled in school, but his professors praised him for his innovative approach to tasks. He was also diagnosed with facial blindness and neuromuscular disease at an early age, which prohibited him from participating in sports and made social parts of school life tough. He thrived in college after opting to pursue a profession in painting.

Early Life

After his junior year at the University of Washington in Seattle, Close won a scholarship to attend the Yale Summer School of Music and Art, which aided his admittance to the Yale MFA programme in 1962. In Yale’s demanding atmosphere, he competed against a slew of outstanding contemporaries, including Nancy Graves, Brice Marden, and Robert Mangold. The new head of the MFA programme, Jack Tworkov, advocated for the inclusion of current art trends (such as Pop art and Minimalism) in addition to the traditional concentration on Abstract Expressionism; the redesigned curriculum had a significant impact on Close’s later work.

Close began teaching lectures at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst in 1965, after finishing his trips overseas. He began experimenting with new shapes and materials after deciding that his own Abstract Expressionist style of painting had become stale. Painting a huge nude from a series of pictures was one of his most ambitious ideas at the time, but he abandoned the project owing to unresolved colour and texture issues. Close had a solo show of other pop-inspired paintings at the college in January 1967, which sparked controversy from the administration owing to his use of full-frontal naked male pictures. Close returned to Manhattan that fall, taking a new teaching post at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, where he reconnected with former student Leslie Rose. In December of that year, the two married. Close’s search for a trademark style was a never-ending source of aggravation for him, and with Rose’s encouragement, he continued to explore many modern art forms. Process work, in particular, was quite popular at the time, because of the increasing renown of Sol LeWitt and others. Returning to the huge photographic-based nude he had started in Amherst, Close decided to take a systematic approach to the challenge.

He parsed the picture into a grid, which he then reproduced onto a nine-foot-long canvas, again using photos. Close created a larger-than-life black and white replica of the female nude’s picture by painstakingly hand-copying the photograph’s gridded segments onto each matching cube of the canvas. Big Nude (1967) is a picture that reads as both abstract and realistic. Furthermore, depending on the viewing distance, the painting seems to be either a classic figure drawing or an abstract landscape of a close-up, hardly identifiable subject.

Mid Life

Close’s career took off after the Walker Art Museum bought a similar-looking Big Self-Portrait (1967-68) in 1969, which led to other sales immediately after. In his first “Heads” series, he tried to perfect his technique, inspired by the newly discovered way of painting. These paintings, which were also in black and white, highlighted their photographic roots. Close utilised the large-scale format to magnify the camera’s less favourable interpretations, resulting in close-up pictures he refers to as “mug shots.” A Close picture of musician Philip Glass was purchased by the Whitney Museum of American Art in December 1969. Close looked to photography for inspiration when he needed to restore colour into his work. Close created a method that used distinct layers of cyan, magenta, and yellow to mimic the photographic dye-transfer process. The hues, which are painted on top of each other, urge the observer’s eye to combine them in order to get a genuine, full-colour image. Kent (1970-71) was the first portrait created using this technique, and it took Close over a year to finish. He worked on three-colour-process portraits for the following few years, during which time his first child, Georgia, was born.

Close was commissioned by Parasol Press to create a series of prints using any manner he wanted in the summer of 1972. Close was intrigued, so he picked mezzotint, a nearly-forgotten printing technique popular in 18th-century portrait reproductions. The print accidentally exposed the schematic checkerboard design while reproducing an existing gridded image of Keith Hollingworth. As a result of these unanticipated outcomes, the same images were used again and over again for paintings using diverse methods and mediums. Fingerprinting, the use of pulp paper, and the quick Polaroid, “snapshot” pictures were among the more unconventional methods he used.

Famous Art by Chuck Close

Big Nude

1967

Close’s distinctive grid method is used for the first time in “Big Nude” and its scale and self-aware title reveal its ambitious nature. The painting’s varied brushstrokes indicate Big Nude to be more of a prototype for future development than a completely resolved picture, yet the transferred image “reads” as a flat reproduction of light and dark characteristics of a photograph. “Big Nude” which is dangerously balanced between a conventional studio exercise in figure drawing and a 1960s girly magazine shoot, also questions the future of representational painting at a time when the genre would appear to have long since exhausted its prospects for further growth.

Kent

1970

For Kent, Close used preliminary sketches for the first time to experiment with the three-color technique, a re-use of the photographic dye-transfer approach. Close believes that illusion is ultimately in the eye of the beholder, whose own optical equipment “completes” the picture by adopting a mechanical method and physically replicating it, or by hand constructing what is typically carried out by the camera. Close was shocked that the piece took three times as long to create, despite the fact that he actually painted the identical picture three times, one on top of the other in different hues.

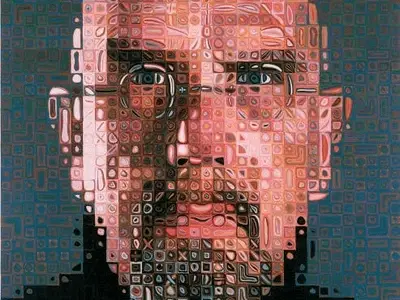

Self-Portrait

1997

In the common imagination, Chuck Close’s art is most typically connected with his own likeness. Close’s self-portraits provide an intriguing arena for measuring the growth of his ideas and work over four decades, despite the fact that he picked them primarily for the sake of convenience. The youthful man’s insouciant look in Big Self-Portrait contrasts sharply with the elder Close’s stolid, knowing gaze as depicted in this 1997 self-portrait. Indeed, the analogy exemplifies the transition from emerging artist to global icon. In comparison to prior work, Closes’ 1990s Self-Portrait demonstrates how abstraction has become increasingly prevalent in his work.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Chuck Close is most known for reviving the art of portrait painting from the late 1960s to the present day, during which time photography was challenging painting’s prior supremacy in this field and slowly earning critical acclaim as an independent creative medium.

- Close arose from the 1970s painting movement of Photorealism, also known as Super-Realism, but went on to explore how methodical, system-driven portrait painting based on photography’s underlying processes (rather than its superficial visual appearances) could suggest a wide range of artistic and philosophical concepts.

- Close’s personal struggles with dyslexia and, as a result, partial paralysis, have also suggested real-life parallels to his professional discipline as if his methodical and yet intuitive painting methods are inextricably linked to his daily reckoning with the body’s own vulnerable, material condition.

- Close quickly moved to portraiture after attaining the glossy, mirror-like “look” of the image in 1970s photorealist painting, suggesting it as a manner of examining disturbing elements of how self-identification is always a composite and highly manufactured, if not ultimately conflicting fabrication.

- The camera’s analytical, serial approach to any given topic is a conceptual parallel to Close’s reliance on the grid as a metaphor for his analytical methods, which indicate that the “whole” is rarely more (or less) than the sum of its parts.

- Every bright, street-smart Polaroid is as much a time-based and fragmented gesture as any more painstaking brushstroke in the cloistered studio.

- Close has experimented with a variety of mediums, including oil and acrylic painting, photography, mezzotint printing, and others.

- Close boldly shifts from one to the other, implying that his conceptual objectives are eternal, yet his means or materials are infinitely interchangeable.

- This is one of the reasons why Close’s portrait painting has stayed unexpectedly “contemporary,” for over four decades, even while the wider trend of Photorealism, his first artistic idiom, has faded into history.

- Close’s slow, accumulative processes, which employ a variety of abstract colour applications in the service of creating “realistic,” or illusory portraits, have recently found application in the art of modern tapestry, thanks to a highly illusionistic, computer-aided method of industrial weaving that Close favours for its ability to suggest the hyper-real appearance of 19th-century glass photographs (daguerreotypes).

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.