(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

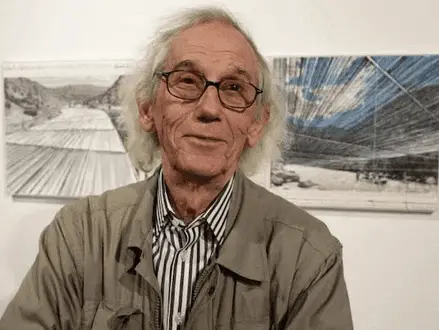

Born: 1935

Died: 2020

Summary of Christo

Christo’s early education in Soviet Socialist Realism, as well as his experience abandoning his country as a political revolution refugee, influenced his career’s repeated incursions into real-world politics as a main topic and source of his work. His 35-year partnership with artist Jeanne-Claude, as well as the large-scale site-specific works they co-authored, are among his career highlights. The pair collaborated on monumentally scaled sculptures and installations, frequently draping or wrapping vast sections of existing landscapes, buildings, and industrial items in specifically designed fabric.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude created works that are among the most enormous, ambitious, and site-specific works ever created. While they frequently claimed that the aesthetic qualities of their work were its primary value, audiences and critics around the world have long recognised a broader commentary running through their work, with themes ranging from environmental degradation to the tumultuous history of the twentieth century and the Cold War, to the persistence of democratic and humanist ideals.

Christo and Jeanne-interventions Claude’s in the natural world and the constructed environment changed the physical shape and visual experience of the locales, allowing viewers to appreciate their formal, energetic, and volumetric aspects in new ways.

The artists’ decision to operate both within and outside of legal structures gives most of their work a built-in element of dissent and resistance. It also builds on and strengthens a long tradition of quasi-legality in art, in which art resides halfway between the “real” world and fantasy, with specific advantages and limits for the art world.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude frequently worked outside of the gallery system, refusing to sell drawings or commissions through a gallery. In this way, they took a firm stance on the global art market’s political and economic architecture, and set a pattern for artists who worked outside the system but nevertheless achieved international acclaim.

Unlike Land Artists, who sometimes blurred the borders between the art piece and its natural location and/or materials, Christo and Jeanne-works Claude’s depended on creating a strong contrast between the constructed, man-made components and the organic qualities of the site. As a result, their work pushes the boundaries of what defines site-specific, large-scale installation art, as well as broadening the genre’s discourse to include contentious issues like industrialization, bureaucratization, and late capitalism.

Early Life

Christo was born in the tiny village of Gabrovo, Bulgaria, amid the Balkan Mountains. Christo Vladimirov Javacheff was his given name, and his parents were Ivan Vladimir Javacheff, a chemist and fabric mill owner, and Tzveta Dimitrova, a political activist and secretary at Sofia’s Academy of Fine Arts. Ivan and Tzveta knew a lot of artists and intellectuals in Gabrovo, and Christo grew up in a world of progressive ideals and culture. Christo began making art at a young age, influenced by his parents’ bohemian social group, and was supported by many professors from the Academy of Fine Arts who visited his parents at their house.

In 1952, Christo joined at Sofia’s Fine Art Academy, where he studied and worked until 1956. The academy’s curriculum centred mostly on Soviet Socialist Realism, a government-mandated style of artistic creation that emerged in the early twentieth century in the Soviet Union as a non-capitalist type of populist art. Christo also joined a campus Communist Youth club, where he helped create propaganda posters based on the principles and techniques of Socialist Realist political art.

Christo moved to Prague, Czechoslovakia, after graduating from the academy. There, he dabbled in theatrical design and studied at the Burian Theatre, where he first encountered Matisse, Miró, Klee, and Kandinsky’s work. The Hungarian Revolution erupted in 1956 during his first year in Prague, posing a particular threat to students and members of the creative and intellectual elite. By paying a railway worker to stow him away on a train carrying medications and medical supplies, Christo was able to flee Hungary.

He made it to Vienna, Austria, safely, but the transfer resulted in his losing his Bulgarian citizenship and becoming a “stateless person,” a UN classification created in 1954 to deal with the post-World War II refugee problem. He spent one semester at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, studying sculpting under the artist Wotruba. He then moved to Geneva for a year before moving to Paris in 1958, where he met his future spouse, Jeanne-Claude de Guillebon, and stayed for the following six years.

Mid Life

Christo struggled to learn the language and adapt into the Parisian society during his early years in the city. He earned a career painting portraits on the street, which he thought did not reflect his ability or real creative identity, so he signed them “Javacheff” rather than his own name. During this time, he encountered artists like as Arman, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely, and Yves Klein, who were all part of the Nouveau Realisme movement, which saw ordinary objects and materials taken and merged into multi-media works. Christo started experimenting with commonplace items like beer cans, bicycles, and traffic signs.

When Christo created a street picture of Jeanne-mother, Claude’s he first met her. He was originally smitten by Jeanne-half-sister Claude’s Joyce, even though she was engaged to Phillipe Planchon at the time. When Christo and Jeanne-Claude discovered that they were born on the same day, in the same year, and at the same hour, they forged an artistic and personal relationship. Even though she was pregnant with Christo’s kid, Jeanne-Claude stayed engaged to Planchon and married him. Christo and Jeanne-son Claude’s Cyril was born in 1960 after she told the truth to Planchon and broke ways with him.

In Paris, the two began collaborating artistically. They experimented with oil barrels, wrapping them initially and eventually constructing large-scale pieces that would later become signatures of the couple’s joint work. In the early 1960s, they began to establish themselves in the city and were regarded as legitimate artists. The pair arrived to New York City in 1964 and lived there as undocumented immigrants for three years, squatting in an illegal building that they finally bought in 1973, when Christo became an American citizen.

Christo developed life-size pieces called Store Fronts and Show Windows, which he sold to help fund his other, less marketable undertakings, such as covering entire buildings in Italy and the United States and working with landscapes from the Australian coast to the Colorado mountain ranges.

Late Life

Jeanne-Claude was first seen as Christo’s publicist and business manager, but her position as his creative and administrative collaborator was subsequently recognised. The duo underlines that everything they’ve done since the 1960s has been a collaborative effort, and they only put Christo’s name on their work for marketing reasons. The pair worked from their New York studio and home, seldom hired help, and self-funded their projects by selling drawings, blueprints, and 3-D models. Their collaboration was so important to their method that they frequently travelled on separate flights to guarantee that if one crashed, the other could keep working.

When Jeanne-Claude had a brain aneurysm in 2009, she was working on two projects at the same time: Over the River in Colorado and The Mastaba in the United Arab Emirates. On November 18, at the age of 74, she died as a consequence of the complications. Since her death, Christo has continued to work on the fulfilment of their large-scale works.

Outdoor works by Jeanne-Claude and Christo are considered as some of the most ambitious and inventive in the world, yet they are frequently contentious owing to their scale and uncertain environmental effect. To address these issues, the artists performed extensive environmental impact assessments and recycled all of the materials that they specifically created.

Famous Art by Christo

Wrapped Coast

1968-1969

In the late 1960s, Jeanne-Claude and Christo covered 1.5 miles of rocky shoreline near Little Bay in Sydney, Australia, with one million square feet of erosion-control synthetic fabric, 35 miles of polypropylene rope, 25,000 fasteners, threaded studs, and clips. Christo had previously experimented with this style of wrapping with smaller items, but this enormous endeavour surpassed Mount Rushmore as the largest single artwork ever made at the time. Beginning on October 28, 1969, it was wrapped for ten weeks.

Valley Curtain

1975

Valley, a 200,200 square foot length of orange woven nylon fabric that extended across an entire Colorado valley, was started by Christo and Jeanne-Claude in the spring of 1970. Between Grand Junction and Glenwood Springs in the Hogback Mountain Range, the massive crescent-shaped cloth was stretched on a steel cable and attached to two mountain peaks. It was anchored with 27 ropes and stretched over the valley at a maximum width of 1,250 feet and a height of 365 feet.

Wrapped Reichstag

1971-1995

The Reichstag in Germany was wrapped with 1,076,390 square feet of thick, glossy aluminum-based polypropylene fabric and 9.7 miles of blue polypropylene rope for this project. The building’s relief faces, towers, and roof were wrapped in vast swathes of fabric, while the remainder was covered with 70 panels of fabric fashioned and created particularly for the facade. The building’s unique characteristics were emphasised by the silvery fabric and blue ropes that surrounded it.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Christo’s early education in Soviet Socialist Realism, as well as his experience abandoning his country as a political revolution refugee, influenced his career’s repeated incursions into real-world politics as a main topic and source of his work.

- His 35-year partnership with artist Jeanne-Claude, as well as the large-scale site-specific works they co-authored, are among his career highlights.

- The pair collaborated on monumentally scaled sculptures and installations, frequently draping or wrapping vast sections of existing landscapes, buildings, and industrial items in specifically designed fabric.

- Christo and Jeanne-Claude created works that are among the most enormous, ambitious, and site-specific works ever created.

- While they frequently claimed that the aesthetic qualities of their work were its primary value, audiences and critics around the world have long recognised a broader commentary running through their work, with themes ranging from environmental degradation to the tumultuous history of the twentieth century and the Cold War, to the persistence of democratic and humanist ideals.

- Christo and Jeanne-interventions Claude’s in the natural world and the constructed environment changed the physical shape and visual experience of the locales, allowing viewers to appreciate their formal, energetic, and volumetric aspects in new ways.

- The artists’ decision to operate both within and outside of legal structures gives most of their work a built-in element of dissent and resistance.

- Christo and Jeanne-Claude frequently worked outside of the gallery system, refusing to sell drawings or commissions through a gallery.

- Unlike Land Artists, who sometimes blurred the borders between the art piece and its natural location and/or materials, Christo and Jeanne-works Claude’s depended on creating a strong contrast between the constructed, man-made components and the organic qualities of the site.

- As a result, their work pushes the boundaries of what defines site-specific, large-scale installation art, as well as broadening the genre’s discourse to include contentious issues like industrialization, bureaucratization, and late capitalism.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.