Feminist Art Simplified

The feminist movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s influenced a wide range of art forms, including feminist art. In feminist art, the societal and political differences women face are depicted to highlight the unique experiences they have.

Summary of Feminist Art

The late 1960s saw the emergence of the Feminist Art movement amid the fervour of anti-war demonstrations in the United States and the burgeoning movements for gender, civil, and queer rights all over the world. Feminist artists drew inspiration from the utopian ideals of early-20th-century modernist movements to rewrite a falsely male-dominated art history, change the contemporary world around them through their art, and challenge the established art canon. Women and minorities had previously been unable to participate in the art world because of the lack of opportunities and spaces that Feminist Art provided.

Women’s perspectives were an important part of feminist artists’ efforts to engage the viewer in conversation with their work. Art was more than just a beautiful object; it had the power to inspire the viewer to question the social and political landscape and, in doing so, potentially change the world. Feminist art, according to artist Suzanne Lacy, aims to “influence cultural attitudes and transform stereotypes.”

Women artists were largely ignored by the public before the emergence of feminism. They were frequently excluded from gallery shows and representation simply because of their gender. Abstract Expressionism’s hard-drinking, womanising members were glamorised in the art world, which was viewed as a boy’s club. Artists of the Feminist movement fought back by creating alternative venues and influencing existing institutions’ policies to increase visibility for female artists in the market.

Textiles and other materials associated with the female gender were often used by feminist artists to create their work rather than painting and sculpture, which had a more male-dominated precedent. Women sought to broaden the definition of fine art by expressing themselves in non-traditional ways and by including a wider range of artistic perspectives.

Feminist art connects women’s voices from all over the world, regardless of where they live. Popular Feminist artists have come from all over the world over the movement’s long history. They represent a wide range of countries and cultures and have fought for equal rights and visibility in their respective cultural landscapes for decades.

An “intersectional” approach has emerged in feminist art and discourse since the 1990s. This means that many feminist artists are exploring not only their own gender identity but also their racial and queer identities, as well as their (dis)abilities.

Why is it Called Feminist Art?

As a category of art, “Feminist Art” emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when feminists were actively engaged in the movement for women’s rights and feminist theory.

Everything About Feminist Art

The Beginnings of Feminist Art

A long history of feminist activism preceded the “second-wave” of feminism in the United States and England in the late 1960s. As early as the mid-19th century, women were fighting for the right to vote, and this movement was known as the “first wave” of feminism. During this early period, no “Feminist Art” was produced, but it laid the groundwork for the activism and art of the 1960s and 1970s, which in turn influenced the art. There was no organised feminist activism during this time period, but women were still concerned about their place in the society..

For example, some artists have been identified as proto-feminists after their death, many of them from Europe and Russia. Even if they did not explicitly identify as feminists, artists like Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois created works that included imagery related to the female body, personal experience, and notions of domesticity. Later, during the “second-wave” of feminism, during the upsurge of the broader women’s movement in the late 1960s, the Feminist Art movement took up these themes. They expanded on the themes that the “second-wave” had already explored, but with a new visual vocabulary and a more explicit connection to the fight for gender equality.

New York City had a well-established art gallery and museum system, so women artists were primarily concerned with equal representation. As a result, they created a number of organisations, such as the Art Worker’S Coalition, Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), and the AIR Gallery, to specifically address the rights and concerns of feminist artists. Museums such as the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art were protested by these groups because they exhibited few or no female artists. There was a dramatic increase in the percentages of female artists included in the Whitney Annual in 1969 and 1970, from 10% to 23%.

Instead of battling an established system, women artists in California focused on creating a new and distinct space for women’s art. As part of the California Institute of the Arts’ Feminist Art Program, artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro organised a massive property in Los Angeles called “Womanhouse” in 1972, where various female artists created on-site installations. Chicago, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, and Arlene Raven founded the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW) in 1973, a two-year programme for women in the arts that covered both studio practise and theory and criticism. FSW was part of the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, which was created by feminist artists as an inclusive space for all women in the community, and contained gallery space as well as cafes and bookstores.

Women artists had been left out of the Western art canon since the 1970s, and art critics played an important role in this movement by drawing attention to this fact. Art critics and aestheticians like them fought hard to overturn traditionally male-dominated fields like art criticism and theory. Linda Nochlin’s provocatively titled essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” was published in ARTnews in 1971. Feminist revision of art history was sparked by the essay’s critical examination of the concept of “greatness” which had been defined primarily in male-dominated terms. The Women’s Art History Collective was founded in 1973 by art critics Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock in England to address the omission of women from the Western art historical canon. When Nochlin and fellow art historian Ann Sutherland Harris put together “Women Artists: 1550-1950” in 1976, they wanted to show the public 400 years worth of work that had gone largely unrecognised until that time.

The new conservatism of the Reagan and Thatcher administrations ushered in an end to the radical idealism of the arts at the end of the 1970s. In contrast to the embodied female experience that dominated 1970s art, the Feminist artists of the 1980s focused more on psychoanalysis and Postmodern theory. Though not always aligned with a unified social movement, artists continued to expand the definition of feminist art and their works still expressed the need for women’s equality. While feminist artists of the 1970s made significant strides, women’s representation was far from equal.

Guerrilla Girls, a group formed in 1985, is best known for its protests, speeches, and performances against sexism and racism in the art world while wearing gorilla masks and adopting pseudonyms to protect themselves from real-world consequences for speaking out against powerful institutions. Posters plastered all over Manhattan by the Guerrilla Girls were the first step in a new direction for feminist art. A political message was conveyed through a combination of humour and clean design in their posters. Additionally, Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger, two 1980s feminist artists known for their use of graphics and catchy slogans that drew inspiration from the visual vocabulary used in the advertising industry, were also interested in mass communication. Feminist artists of the 1970s focused more on the differences between men and women, but these artists aimed to destroy male-dominant social precepts rather than to celebrate them.

Concepts in Feminist Art

For Feminist artists, there is no single medium or style that binds them together, as they often incorporated elements from a variety of other movements into works that conveyed the need for gender equality.

Feminist Performance and Visual Art Since performance was a direct means for female artists to communicate a physical, visceral message in the 1970s and beyond, art often crossed paths. It gave the impression of being right in front of the viewer, making it more difficult to ignore.. As there was no separation between the artists and the work, performance kept the work on a very personal level.

In addition to painting and sculpture, body art was a popular medium for Feminist artists because it allowed the creators to communicate directly with the audience about their innermost thoughts and feelings. Feminist art made extensive use of both body and performance art.

Like Feminist Art, video art emerged in the art world only a few years before its predecessor and provided a medium with no prior precedent set by male artists. The Feminist Art movement saw video as a way to reach a wider audience by democratising access to television broadcasting technology and thereby kicking off a media revolution. The Los Angeles Women’s Video Center (LAWVC) was housed in the Woman’s Building, giving female artists in Los Angeles unprecedented access to the high-tech equipment needed to create video art.

In her 1973 series Maintenance Work, Mierle Laderman Ukeles investigated the idea of women’s work by performing everyday household tasks inside a museum. Viewers were forced to walk around her as she cleaned the steps leading to the entrance, and even mundane tasks were elevated to the level of art. Reclaiming the vagina as sacred source and birth passage was Carolee Schneemann’s goal when she pulled a scroll from her vagina in public. A performance by Yoko Ono where she sat submissively on stage as audience members were invited to cut off her clothes revealed her own vulnerability, The “knowledge is power” model was used by these artists to influence new ways of thinking about traditional female stereotypes and to inspire empathy and compassion for the female condition by sharing gender specific experiences with audiences.

In order to convey a deeply felt experience in the most visceral way possible, artists often distorted images of themselves, changed their bodies with other materials, or performed self-mutilation. Blood and the artist’s own body were used in Ana Mendieta’s performances, creating a primal but nonviolent connection between the artist’s body and her audience (and nature). Feminist artists, including Mendieta, saw blood as a powerful metaphor for a woman’s fertility and life.

To combat sexism and oppression, many feminist artists created works that defied the traditional view of women as beautiful objects to be admired. When women use their own bodies in their art, they are using themselves; a significant psychological factor converts these bodies or faces from object to subject. ‘ Viewers were compelled to question social and political norms by these works.

Video artist Dara Birnbaum, for example, used video art to deconstruct the media’s representation of women by appropriating and re-presenting images from television broadcasts in her video-collages. She used images from the popular hit television show Wonder Woman to expose its sexist subtexts in her most prominent piece, the 1978-79 video Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman. Judith Bernstein, a colleague of Birnbaum’s, was well-known for her use of sexually explicit images, many of which drew inspiration from the male phallus and were reminiscent of graffiti-scrawled men’s restroom signs. In Horizontal (1973), her monumental drawing, a domineering, swirling screw is depicted.

For works she began making in the 1970s that combined fabric, paint, and other materials by using “femmage” Miriam Schapiro coined the term “traditional women’s techniques – sewing, piercing, hooking, cutting, appliqueing, cooking and the like…” “women’s work” was highlighted as a viable alternative to “high art.” as a result of this. Some artists, such as Faith Wilding and Harmony Hammond, have used fabric in their work to question the exclusion of feminine craft from the arts.

Martha Rosler investigated the many facets of being a woman and a housewife. We see a video of a woman describing her attempts to better herself and her family through gourmet cooking in her 1974 film A Budding Gourmet. Slides from glossy food and travel magazines randomly interrupt her dialogue, depicting consumerism’s baiting of the everyday housewife.

In an effort to highlight the lack of women in historical cultural texts and documentation, a number of feminist artists created art. Many contemporary female artists have been influenced by Frida Kahlo, Lee Krasner, Gertrude Stein, and others in Judy Chicago’s seminal Dinner Party, 1974-1979. Nancy Spero, a prominent feminist artist, was a major force in the movement to dismantle male dominance. Using a long scroll-like format, her 1979 work, Notes in Time, explores the role of women throughout history, traversing eras, continents, and space to give them the documentation and significance they have long deserved.

The End of Feminist Art

The Feminist Art movement had a major impact on the art world of its time, according to Kiki Smith “A lot of the art we take for granted and the subject matter we assume to be covered by art wouldn’t exist without the feminist movement, and I wouldn’t be here today if it weren’t for it. Feminism has broadened our understanding of art, including what it is, how we view it, and who is included in it. It sparked a major shift in society, in my opinion. You don’t want to create the cultural stereotype that only one gender is capable of original thought. All of us, regardless of our gender, sexual orientation, or other self-definitions, are inherently creative beings. To not embrace feminism as a model, like many other liberation models, is against the interests of the culture at large, because they liberate not only women, but everyone.”

Many contemporary female artists no longer feel the need to identify as “women artists” or to explicitly address the “women’s perspective.” because of the progress made by previous generations of feminist artists. More and more female artists began to produce work that was more focused on their own personal issues and less about the larger feminist movement.

Photographers such as Cindy Sherman have reappropriated iconic stereotypes from film and history to question the male gaze that pervades film theory and popular culture. Cindy Sherman’s work is an example of this. For example, in Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998), which featured her own slept-in bed covered in used condoms and blood-stained underwear, the influence of Feminist Art could be seen in the use of personal narratives and unconventional materials. Even if they aren’t labelled as feminist, these diverse practises have their roots in the first and second generations of feminist artists and critics and can be traced back to their use of materials, roles, and perspectives.

With the exhibition WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, the Feminist Art movement received its due in the annals of art history in 2008. From around the world, 120 artists and artists’ groups took part in the groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

The term “intersectional” has come to mean a lot in feminist art and writing these days. Intersectionality is a term coined by feminist legal scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989 to express the idea that people’s identities, such as gender, race and sexual orientation aren’t discrete parts of themselves to be studied separately, but rather should be seen as overlapping parts of one’s self that compound the power imbalances that people face. This approach to identity has been used by proto-feminist and feminist artists for much longer than the term and theory of “intersectionality” which only appeared in the last few decades. When it comes to the gender identity of artists like Mexican painter Frida Kahlo and South African artist Helen Sebidi, their work is intertwined with their struggles as women of colour as well as their struggles as women.

Female sexuality and body image continue to be politically charged and to express the conflict between private life and public life. They continue to be a political issue. Women artists like Kara Walker and Jennifer Linton continue to speak out against sexism and inequality in their work today. Artworks by artists such as Mickalene Thomas and Mary Schelpsi show the subject repeatedly, with Schelpsi’s Beauty Interrupted, 2001, showing a model walking down a runway covered in a blur of the artist’s white brush strokes that obscure both her eyes and her rail thin ideal. In contrast to the Feminist Art movement, which opened the way for these vital discussions, female artists are continuing to highlight the pervasiveness of the issues it raises.

Key Art in Feminist Art

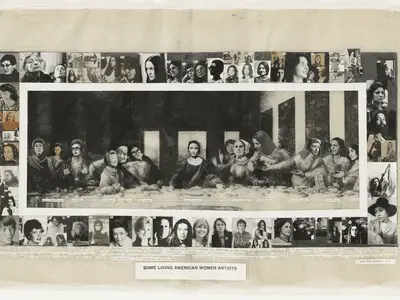

Some Living Women Artists/Last Supper

By Mary Beth Edelson

1972

She used a picture of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous mural as the basis for this collage and added the heads of notable female artists to replace those of the original men. A picture of Georgia O’Keeffe was placed on Christ’s body. Additionally, the painting’s male-only club challenged the religious subordination of women. Women’s erasure from history was a major goal of Feminist Art, and this image became a symbol of the movement’s efforts.

ArtForum Advertisement

By Lynda Benglis

1974

Angry at being marginalised in an art world dominated by men, artist Lynda Benglis created a series of advertisements for magazines that poked fun at stereotypical portrayals of women. One of her most well-known ads, which appeared in ArtForum, featured a photo of her bare-naked, holding a dildo with two heads and wearing shades to promote her upcoming show at Paula Cooper Gallery. It cost her just $3,000 for the ad, which would go on to establish her as a major figure in the history of feminist art. Even more importantly, Benglis was able to guarantee the uncut transmission of her message because she paid for the advertisement. The dildo sculptures she made later on were a cheeky “f*** you” to the male-dominated art institutions she was protesting against.

Anatomy of a Kimono

By Miriam Schapiro

1974

One of Schapiro’s many “femmages” Anatomy of a Kimono is based on the patterns of Japanese Kimonos, Fans, and Robes and was created in the 1970s. It was Schapiro’s idea to use the term “femmage” to describe works that incorporated a variety of “high art” and “decorative art” techniques while also emphasising women’s relationship to the materials and processes involved in creating them.

Interior Scroll

By Carolee Schneemann

1975

At the “Women Here and Now” exhibition in 1975, Carolee Schneemann performed the unforgettable Interior Roll. She stripped down to her apron in front of the audience for the performance. The book by Cézanne, She Was a Great Painter (1975) inspired her to begin painting her own body. Once her clothes were off, she began reading aloud from a scroll of paper that had been pulled from her vagina. Filmmaker talked about women and how they couldn’t access certain traits, like logic or rationality, he claimed to be male-specific. The text was inspired by this recording. As a result, he concluded that women were only capable of stereotypical attributes like intuition, emotion, and so forth. Schneemann made the point that only a woman could truly represent or speak on behalf of the female experience – anything else was just hearsay. She showed that she was no longer interested in suppressing her authentic femininity or asking for permission to fully inhabit her female sexuality or reality by placing her vagina front and centre and using it to birth a provocative message.

THE ADVANTAGES OF BEING A WOMAN ARTIST

By The Guerrilla Girls

1989

To defuse and break down discrimination in the art world, the Guerrilla Girls used humour. This is one of their early posters. To make light of the “advantages” that women artists had in the late 1980s, they list things like “Knowing your career might pick up after you’re eighty.”

The Guerrilla Girl “High art, according to Lee Krasner, “is run by a small group of people who get their work into museums and history books. These people, no matter how intelligent or well-intentioned, have repeatedly shown a bias against women and artists of colour.” In 1989, despite nearly two decades of feminist activism, this poster shows how pervasive that bias was. The fact that the Guerrilla Girls are still making posters and appearing around the world suggests that this issue is still a problem.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.