Expressionism Simplified

Expressionism is a twentieth-century art and culture trend. The art aims to elicit an emotional response and to convey personal feelings and thoughts. Rather than expressing physical truth, expressionist painters tried to communicate the notion of “being alive” and emotional experience.

Summary of Expressionism

As a response to widespread worry over humanity’s increasingly dissonant connection with the planet, as well as accompanying lost sense of authenticity and spirituality, expressionism arose concurrently in several towns across Germany. Expressionism was significantly influenced by Symbolist currents in late-nineteenth-century painting, and was also a response to Impressionism and academic art. The Expressionists were notably influenced by Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and James Ensor, who encouraged the distortion of form and the use of powerful colours to communicate a range of worries and yearnings.

The Expressionist movement’s classic era spanned about 1905 to 1920, and it expanded across Europe. Many people and organisations, including Abstract Expressionism, Neo-Expressionism, and The School of London, would subsequently benefit from its example.

With the introduction of Expressionism, new criteria in the creation and evaluation of art were established. The criteria for judging the quality of a piece of art became the character of the artist’s sentiments rather than a study of the composition, and art was now supposed to emerge from within the artist rather than a portrayal of the exterior visual world.

In depicting their topics, Expressionist artists frequently used swirling, swaying, and exaggeratedly produced brushstrokes. These approaches were intended to portray the artist’s turgid emotional condition in response to the modern world’s worries.

Expressionist artists created a forceful form of social critique in their serpentine figural representations and bright colours as a result of their encounter with the metropolitan life of the early twentieth century. Their depictions of the contemporary city included alienated people – a psychological by-product of recent urbanisation – as well as prostitutes, who were utilised to remark on capitalism’s involvement in the emotional separation of people inside cities.

Why is it Called Expressionism

The word “expressionism” “was probably first applied to music in 1918, particularly to Schoenberg,” since, like Kandinsky, he eschewed “traditional forms of beauty” in his music to convey intense sentiments.

The word “Expressionism” is considered to have been invented by Czech art historian Antonin Matejcek in 1910, with the intention of denoting the polar opposite of Impressionism. Unlike the Impressionists, who used paint to portray the majesty of nature and the human form, Matejcek claims that the Expressionists used paint to express their inner lives, frequently via the depiction of harsh and realistic subject matter. However, neither Die Brücke nor comparable sub-movements ever identified to themselves as Expressionists, and the word was extensively used in the early years of the century to refer to a number of styles, including Post-Impressionism.

Everything About Expressionism

The Beginnings

Upheavals in creative techniques and vision emerged around the turn of the century in Europe as a response to fundamental shifts in society’s environment. Artists addressed the psychological influence of new technology and large urbanisation efforts by shifting away from a realistic portrayal of what they saw and toward an emotional and psychological interpretation of how the environment affected them. Certain Post-Impressionist painters, such as Edvard Munch of Norway and Gustav Klimt of the Vienna Secession, are credited with establishing the foundations of Expressionism.

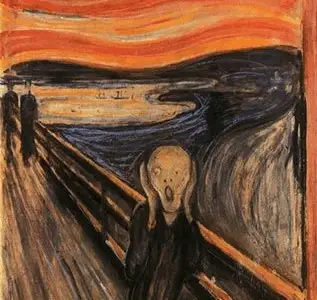

Edvard Munch, a late-nineteenth-century Norwegian painter, became a major source of inspiration for the Expressionists. His colourful, emotionally charged compositions provided new avenues for introspective expression. Munch’s frenzied paintings, in particular, reflected individual angst amid a more modernised European society; his renowned painting The Scream (1893) exemplified the clash between spirituality and modernity as a key topic of his work. Munch’s work was well-known in Germany by 1905, and he spent a lot of time there, placing him in close touch with the Expressionists.

Gustav Klimt, who produced in the Austrian Art Nouveau style and led the Vienna Secession in the late nineteenth century, was another individual who influenced the development of Expressionism. Klimt’s extravagant style of portraying his figures in a vivid palette, intricately patterned surfaces, and elongated bodies was a precursor to the later Expressionists’ exotic hues, expressive brushwork, and jagged shapes. Klimt was a mentor to painter Egon Schiele, and at an exhibition of their work in 1909, he exposed him to the works of Edvard Munch and Vincent van Gogh, among others.

Although it featured a wide range of artists and genres, Expressionism began in 1905, when Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Erich Heckel, four German architecture students who wanted to be painters, established the group Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden. After Wassily Kandinsky’s work The Last Judgment (1910) was rejected from a local show, a group of like-minded young painters established Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in Munich in 1911. In addition to Kandinsky, members of the loosely connected group included Franz Marc, Paul Klee, and August Macke, among others.

Concepts in Expressionism

Members of the Dresden-based Die Brücke group attempted to communicate raw emotion via startling pictures of modern life, influenced by painters like as Munch, van Gogh, and Ensor. They showed city residents, prostitutes, and dancers in the city’s streets and nightclubs, exposing German society’s filthy underbelly. They emphasised the alienation inherent in modern society and the loss of spiritual communion between individuals in urban culture in works like Kirchner’s Street, Berlin (1913); fellow city dwellers are distanced from one another, acting as mere commodities, as the prostitutes at the centre of Kirchner’s composition.

In 1906, the group released Programme, a woodcut broadsheet that accompanied their debut show. It summed up their rejection of existing academic traditions in favour of a more liberated, youth-oriented aesthetic. Despite the fact that it was mainly authored by Kirchner, this billboard functioned as a manifesto for Die Brücke’s ideas. In terms of both their creative aim and intellectual basis, Die Brücke members leaned heavily on the teachings of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. “What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end,” According to Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-85), “What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end.”

Der Blaue Reiter’s painters have a similar interest in abstraction, symbolic meaning, and spiritual allusion. Through highly symbolic and brilliantly coloured representations, they aimed to communicate the emotional elements of existence. The horse and rider emblem, drawn from one of Wassily Kandinsky’s paintings, became their moniker; for Kandinsky, the rider signified the journey from the material world to the spiritual realm, and therefore served as a metaphor for creative activity. Other members, such as Franz Marc, Paul, Klee, and Auguste Macke, adopted this idea as a key concept for moving beyond realism and towards abstraction.

Despite the fact that Der Blaue Reiter never issued a manifesto, its members were bound together by their aesthetic innovations, which were influenced by mediaeval and primitivist art traditions, Cubism, and Fauvism. The ensemble, however, was short-lived; when World War I broke out in 1914, Franz Marc and Auguste Macke were recruited into German military duty and died shortly thereafter. Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, and other Russian members of the group were all compelled to return home. Der Blaue Reiter vanished very quickly after that.

Because of Expressionism’s pliability, it has been associated with numerous artists outside of Germany. Georges Rouault, a French Expressionist who inspired the Germans rather than the other way around, may have influenced them. Rouault inherited his vivid use of colour and distortion of form from Fauvism, and unlike his German Expressionist peers, he professed admiration for his Impressionist forefathers, notably Edgar Degas’ work. He is well-known for his dedication to religious topics, notably his numerous portrayals of the crucifixion, which are richly coloured and layered with paint.

Marc Chagall, a Russian-French Jewish artist, combined elements of Cubism, Fauvism, and Symbolism to develop his unique style of Expressionism, in which he frequently painted dreamlike vistas of Vitebsk, Belarus. Chagall developed a visual language of eccentric motifs while living in Paris during the height of the modernist avant-garde: “ghostly figures floating in the sky, the gigantic fiddler dancing on miniature dollhouses, the livestock and transparent wombs and, within them, tiny offspring sleeping upside down.” His art was shown in Berlin in 1914, and it had an effect on the German Expressionists that lasted far beyond World War I.

Chaim Soutine, a Russian-Jewish painter living in Paris, was a key figure in the creation of Parisian Expressionism. He created an original method and interpretation of the style by combining aspects from Impressionism, the French Academic heritage, and his own particular vision. The artist’s emotive approach has had a huge impact on future generations.

German Expressionism inspired Austrian artists such as Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele, but they interpreted the style in their own unique and personal ways, without creating an official organisation like the Germans. Both Kokoschka and Schiele tried to portray the decadence of contemporary Austria by similarly emotive images of the human body; both painters infused their subjects with extremely sexual and psychological elements through sinuous lines, gaudy colours, and deformed forms. Despite the fact that Kokschka and Schiele were the movement’s main proponents in Austria, Kokoschka got increasingly involved with German Expressionist groups, eventually leaving Austria and settling in Germany in 1910. In his early portraits, Kokoschka painted in a Viennese Art Nouveau manner, but starting in 1908, he intuitively worked as an Expressionist, fervently striving to uncover the sitter’s inner sensibility. Schiele left Vienna in 1912 but stayed in Austria, where he worked and exhibited until 1918, when he died as a result of the global influenza epidemic.

The End of Expressionism

While some painters abandoned Expressionism, others continued to build on the style’s ideas. In the 1920s, for example, Kandinsky moved away from figurative representation and into entirely non-objective paintings and watercolours that focused on colour harmony and archetypal shapes rather than realistic depiction. However, Expressionism’s biggest immediate effect would be in Germany, where it would continue to dominate the country’s art for decades. Expressionism began to lose steam and disintegrate after World War I.

The Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement arose as a direct response to Expressionism’s highly emotive beliefs, while Neo-Expressionists appeared much later in the twentieth century in Germany and the United States, reviving the older Expressionist style.

“Expressionism…no longer has anything to do with the efforts made by active people.” declared the Dada manifesto in 1918. But its spirit would live on; it was crucial in the early formation of painters Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann, who together founded the Neue Sachlichkeit movement (New Objectivity). As the name implies, these artists were looking for a non-emotional and objective approach to creative creation. Their realistic depictions of persons and urban landscapes emphasised this new style while also reflecting the Weimar culture’s general pragmatic mentality.

In the 1960s, Georg Baselitz’s paintings of layered, vibrant colours and distorted figures, and in the 1970s, Anselm Kiefer’s images buried beneath thick impasto built up from a variety of materials on the canvas, signalled a significant and influential revival of the style within Germany, which would eventually culminate in a global Neo-Expressionist movement in the 1980s. To harken back to the Expressionist movement earlier in the twentieth century, artists in New York City, such as Julian Schnabel, used thick layers of paint, strange colour palettes, and expressive brushwork.

The original Expressionist movement’s ideals on spirituality, primitivism, and the importance of abstract art influenced a variety of unrelated groups, including Abstract Expressionism. The Expressionists’ philosophical worldview and innate dissatisfaction with the modern world drove them to hostile attitudes that would persist throughout the century in various avant-garde movements.

Key Art in Expressionism

The Scream

By Edvard Munch

1893

Munch concentrated on death, anguish, and anxiety in deformed and emotionally charged pictures throughout his creative career, all subjects and techniques that would be embraced by the Expressionists. Munch shows the conflict between the individual and society in his most renowned painting. The Scream’s setting came to Munch as he was walking over a bridge overlooking Oslo; as he remembers, “The sky had become blood-red. I came to a halt and leaned against the fence, trembling with terror. Then I heard nature’s colossal, endless cry.”

Sitting Woman with Legs Drawn Up

By Egon Schiele

1917

Schiele is recognised for his startling and often grotesque depictions of overt sensuality, making him one of the key protagonists of Austrian Expressionism. Schiele depicts his wife, Edith Schiele, in a half-dressed state, her body twisted in an unnatural way. Her strong and passionate expression completely violates artistic norms of passive feminine beauty by immediately confronting the observer. Schiele was known for his excellent draughtsmanship and use of sinewy lines to depict the extravagance and depravity of contemporary Austria, despite being unashamedly contentious during his lifetime. Schiele’s expressive line-work and colour position him firmly in the Expressionist movement.

Portrait of a Man

By Erich Heckel

1919

Heckel, a founding member of Die Brücke, worked extensively with woodblock printing, a popular medium among Expressionists, and was first drawn to the method because of its raw emotionalism and harsh aesthetic, as well as its historic German history. In this melancholy self-portrait from 1919, Heckel takes on a more contemplative topic than many of his other works, which feature nudes and scenes of city life. The individual’s spiritual, psychological, and bodily exhaustion is highlighted by the figure’s drawn face, twisted jaw, and weary eyes, which seem to look distractedly into the distance.

Mad Woman

By Chaim Soutine

1920

Soutine created two versions of Mad Lady (each depicting a different woman), and this was definitely the darker of the two. His brusque brushstrokes and twisted lines convey an almost unsettling tension, but his subject retains a deep depth of personality. Soutine encouraged visitors to pay great attention to the subject, peering into her eyes and studying her asymmetrical face and shape. This picture epitomises the Expressionist approach in many ways; Mad Woman clearly vibrates, contorts, twists, pushes, and pulls, giving the viewer with Soutine’s depiction of his sitter’s inner agony. It altered the genre of portrait painting in certain ways.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.