When making a drawing, all artists, regardless of talent level, employ five fundamental skills. These abilities are essential for making any type of artwork, including landscapes, portraits, still lives, and cartoons. When looking at elaborate drawings, it’s easy to forget that any excellent work begins with a pencil and paper, as well as these five fundamental abilities.

Understanding the ability to work with the following are among the 5 fundamental sketching skills: 1) Edges 2) Spaces 3) Light and Shadow 4) Relationships 5) The Whole, or Gestalt. When these five fundamental drawing abilities are combined, they form the components of a finished work of art.

You might be perplexed as to how five skills may serve as the foundation for all forms of sketching. It astonished me at first as well. You’ll notice, though, that each of these abilities covers a lot of ground. Consider how broad a concept like “light and shadows” is.

Even though five abilities may not seem like a lot, mastering each one takes a long time. Let’s take a closer look at each of them individually.

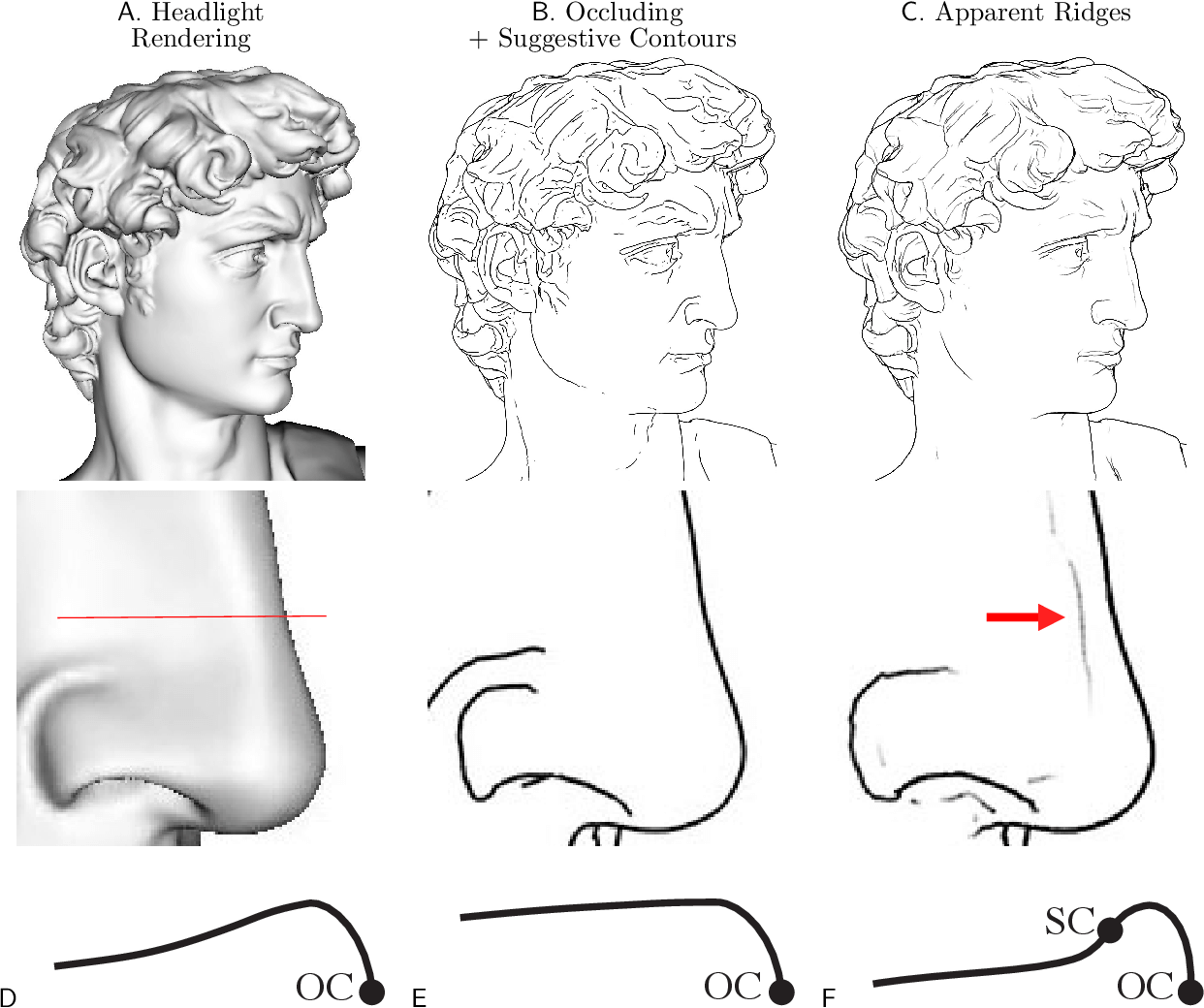

1. Edges:

Every defined form is merely a collection of edges or sides. A simple line drawing, a stippling piece, a complex still life, or a flowing landscape all require an understanding of how edges operate in order to show you what’s going on and the forms that should be presented.

Let’s go right back to the basics here. A square has four sides, a triangle has three sides, and a circle has none. It was pounded into our heads at a young age that if we formed a form with three sides by mistake, it couldn’t be a square. There have to be four sides to a square. For the rest of our lives, every square we would come across in the world would have four sides. We began to comprehend the world via these boundaries.

As artists, we begin to engage with a greater number of edges. We’ve given up counting them since there are so many. What is the number of edges on a hand? Probably quite a bit. It would be a waste of time to count. However, every time you build a section of the hand’s shape, you’re creating an edge. And, maybe more significantly, you’re deciding on that edge. What is its location? What’s the angle? How long should it be?

The difference between drawing a hand that looks like a tree and drawing a hand that looks like it might jump off the paper as a real hand is understanding how edges function and being able to draw them precisely. These edges aid in determining the forms required for your artwork.

2. Space:

When we say “space,” we’re referring to both the space that your subject occupies and the space that it does not occupy. Consider a doughnut. The warm, fluffy dough defines a doughnut, but the hole in the centre, or the empty space, also defines it. This is technically known as ‘negative space’.

Every form occupies a certain amount of space. Negative space is the area that it does NOT occupy. In certain cases, such as with a ball, the negative space is just what is outside of the item. Or it might be included within the item, such as a doughnut. You must grasp both of these principles and how they interact in order to create proper forms.

Consider negative space to be nothing more than a collection of forms.

Artists who are stuck sketching an item might benefit from looking at negative space. Many painters get sucked into concentrating just on the shapes they’re creating. Alternatively, there’s the doughnut. You’ll have an easier time sketching both the doughnut and its hole if you realise that the hole is just as much of a form as the doughnut itself.

Rather, concentrate on the negative space. Because our minds are accustomed to seeing a doughnut as a doughnut, this method works. It’s a familiar thing; therefore, it’s difficult for us to separate it from the pictures we remember of it. When we examine the doughnut’s negative space, though, it becomes more abstract.

Suddenly, we’re looking at a collection of forms rather than a single subject. Because our brains don’t grasp what we’re looking at, they break it down into simple components. From a fundamental form standpoint, looking at negative space might help you see what’s going on.

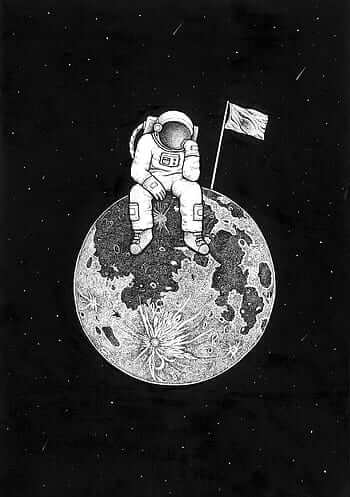

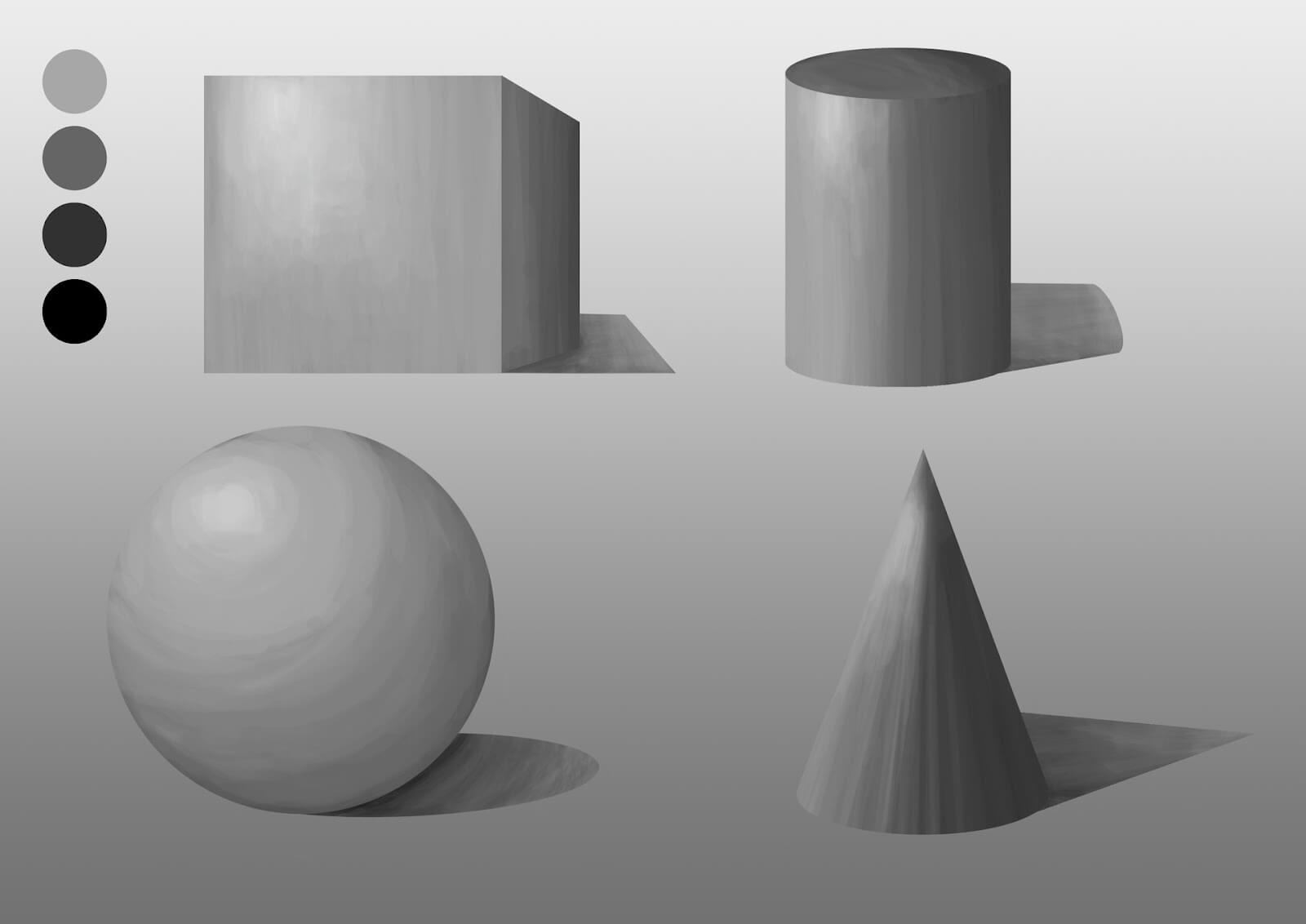

3. Light and Shadow:

Consider glancing at your room when the lights are turned out in the middle of the night. Consider what would happen if you abruptly flipped the switches and were swamped with light.

You couldn’t see any forms in one case because the room was so dark. The next moment, the room was so bright that you couldn’t see anything without straining. This isn’t a perfect representation of how lights and shadows operate, but it is a representation of how we see them. Alternatively, we don’t notice them.

We can’t tell one thing from another when there are too many shadows, such as when we’re in a totally black room.

The scenario is the same when we turn on the lights and get dazzled to the point of squinting. It’s not a good idea to have too much shade or too much light. To comprehend what a form is and how it operates in the environment, you need a balance of both.

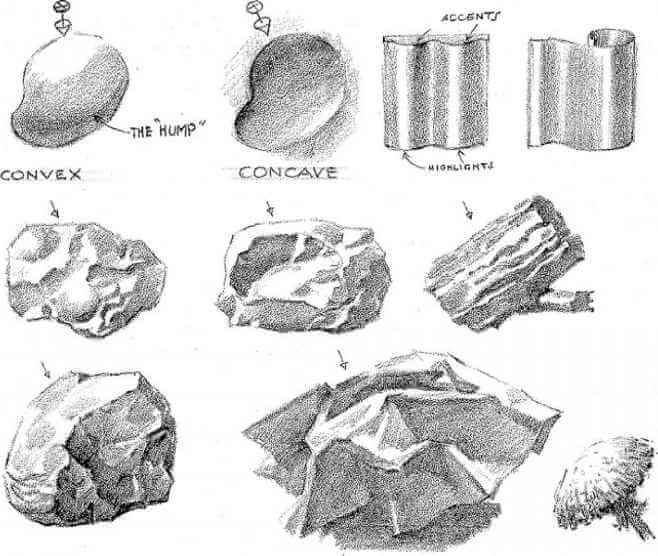

When light strikes an item, it creates light and shadow, which give it shape and depth, making it appear more lifelike.

To express light and shadow in an item, many painters use shading. The more shade there is, the darker the shadow. The highlight will be lighter if the shading is lighter.

To comprehend light and shadow, you must first comprehend colour. Even if you’re using a graphite pencil to create a black-and-white image, your reference image will almost certainly be in colour. Even if your reference photo is in black and white, it’s still crucial to know how the colours in that picture play a part.

We live in a world of many hues. When light strikes an object, it changes the colours we see, which affects how we sketch light and shadows. Take note of how bright lights diminish colours until they are nearly completely gone. Observe how shadows subdue colours until they are nearly saturated. This awareness of colour will affect the tones of your shadows and highlights if you’re sketching in black and white.

When you’re sketching in colour, it’s obvious that colour knowledge is essential. Examine the colours of an object as the light falls on it. It’s not as if you’re suddenly pressing harder or lighter on the same coloured pencil hue. No, those bright and dark colours are entirely distinct hues of the same value. Consider how light and shadow alter and broaden your colour palette.

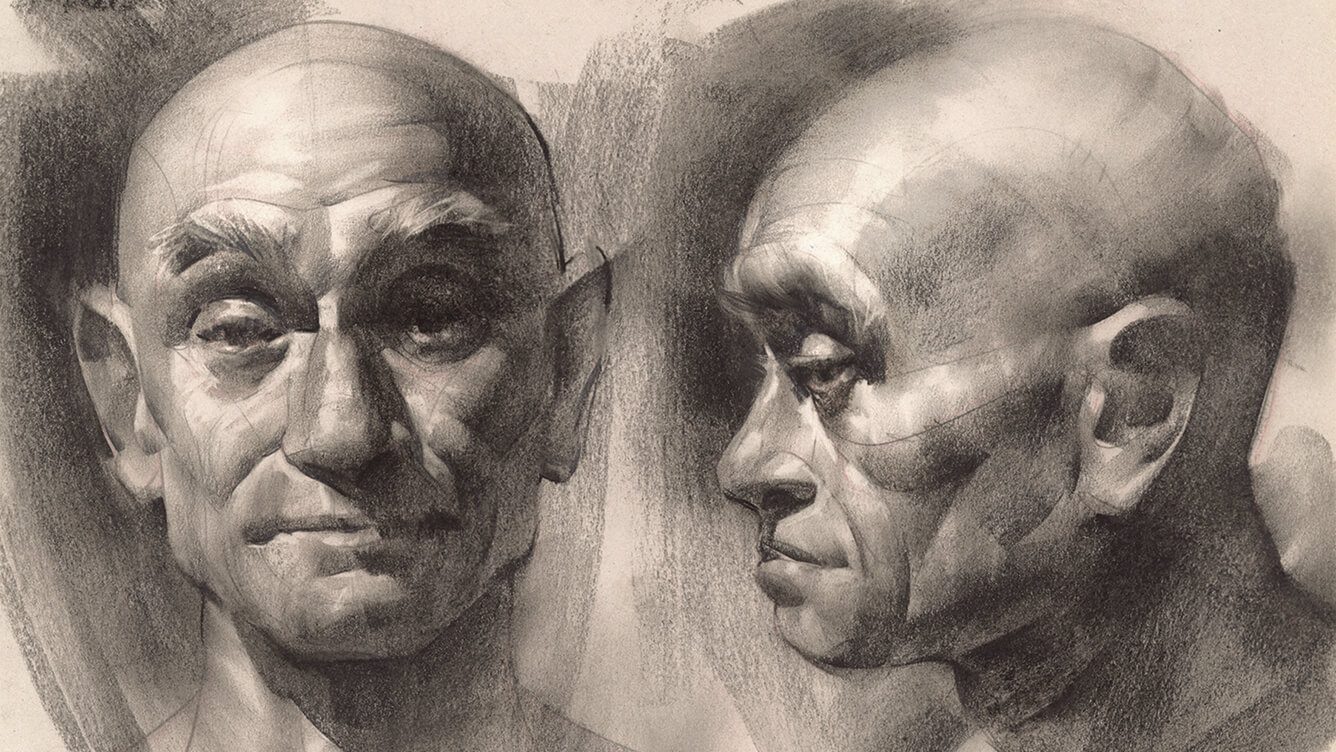

4. Relationships:

Every line on the paper has a relationship with every other line on the paper when you’re sketching. Do you recall that a square has four sides?

We may wind up with a strange-looking abstract inchworm if we don’t connect those sides together correctly. To make a square, all of the sides must co-operate. They can’t be viewed as separate lines. How do the lines we’re working on come together to form the forms we’re working on? A hand is only a hand if it has a specific amount of rounded, curved, and straight lines that join together to make a hand’s shape.

Objects must work together with other objects in the same manner that the lines of an item must work together to provide an accurate picture of that subject. If I place an apple next to a tree on the same plane, the tree must be larger than the apple.

Every single item you create on your sheet of paper has a connection to everything else on the page. To ensure that your entire work of art makes sense, you must ensure that these relationships make sense.

In order to make the interactions between your items work, you may need to master sophisticated concepts like perspective. If the tree is a mile behind the apple and our viewpoint is directly in front of the apple, it would make sense for the apple to be larger than the tree.

However, in order for it to function, you must nail that viewpoint.

Consider how all of your pieces work together to create your ultimate piece of art while you’re looking at your drawing. If anything doesn’t seem right, check the relationships, whether they’re within the item or between the items on the page.

Before you begin, it’s critical to understand the relationships inside your drawing.

Making a rudimentary drawing of where all of your things will go before you start may be really useful. This will let you know if there are any possible snags before you get too far.

5. The Whole, or Gestalt:

This final one is a little deceptive. It isn’t a brand-new, stand-alone skill. Instead, it’s the capacity to combine all skills from 1-4. You’ve probably noticed that skills 1-4 are rather similar. For example, the lights and shadows we discussed in 3 are frequently used to generate the borders from 1.

Despite the fact that they are separate skills, they have a lot in common and may be employed together. They should, in fact, be used together. This is where skill number 5 comes in.

We naturally incorporate all of the abilities we’ve discussed when we draw. As we construct the borders of our subjects, we generate negative space. As we learn how one thing is positioned in relation to another, we produce light and shadow. As artists, we naturally work on combining these talents on a daily basis. These are the abilities we want to master.

Do you have mastery of all four of the talents we’ve discussed as an artist?

No, neither do I. These are abilities that we will all be working on for the rest of our artistic life, regardless of our talent levels. Even when we believe we’ve mastered one of them, there’s always a way to take it to the next level or merge it with another ability we haven’t tried yet.

We’ll never run out of opportunities to develop.