Fauvism and Expressionism

Fauvism, derived from the French word 'fauves' meaning 'wild beasts,' emerged in the early 20th century, deviating from Impressionism's gentle whispers. Artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain favored bold colors and simplified forms, capturing nature's emotional resonance rather than its mimicry.

Expressionism took hold in Germany and central Europe, viscerally rendering emotion on canvas. Wassily Kandinsky and Edvard Munch explored the human psyche's chaos, disregarding aesthetic conventions. Their approach mingled with the era's sociopolitical turmoils, reflecting societal shifts. Munch's 'The Scream' epitomizes this theater of pain, a visual symphony of psychic disturbance.1

These movements challenged taboos and redefined art's subject matter, extending the boundaries of color and form to narrate human experience. Fauvists liberated color from natural law, while Expressionists brutalized shapes and forms. Their legacy intertwines a rejection of realism and prefiguration of later explorations in abstraction and conceptual articulations.

Cubism and Futurism

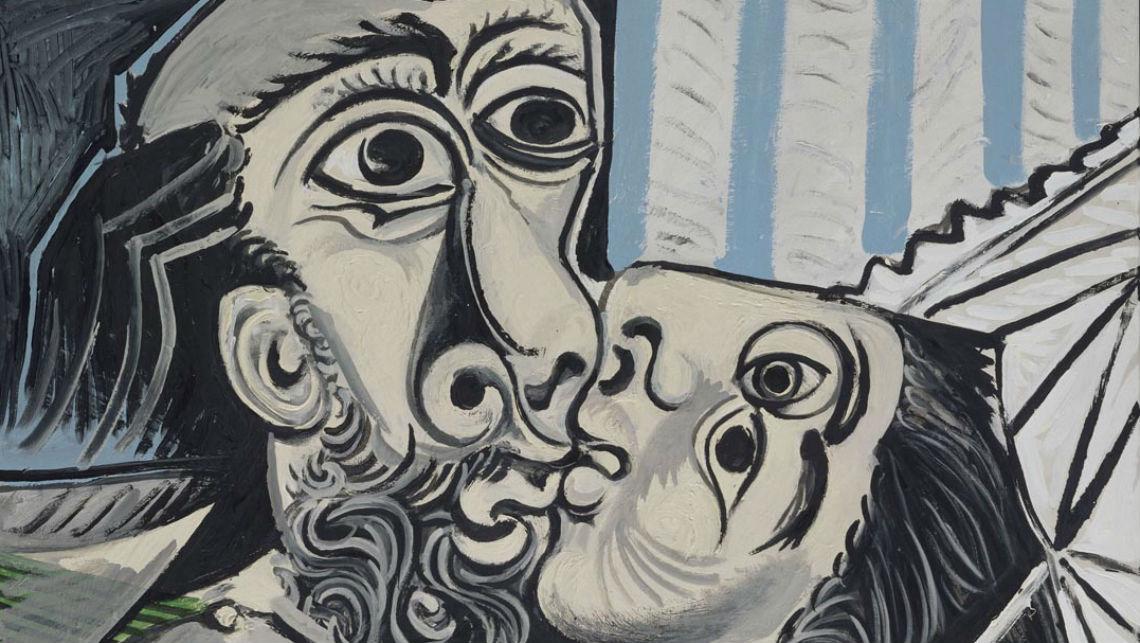

Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, dissected old perspectives, presenting the world from multiple angles within a single frame. This approach rebooted the principles of figure and space, requiring viewers to piece together images and meaning from the visual jigsaw puzzle. Picasso's 'Les Demoiselles d'Avignon' (1907) fiercely deconstructed traditional portrayal of form, mocking classical sensibilities.

Futurism, catalyzed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, thrived on a lust for modern velocity and technological advance. Born from a 1909 manifesto, Futurism celebrated speed, machinery, and youth, embracing the industrial age's aggressive energy.2 Artists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla expressed the era's kinetic frenzy and vibrational energy. Boccioni's 'Unique Forms of Continuity in Space' (1913) sculpts fluid motions, cascading over rigidity of form.

- Both movements decentralized old-fashioned viewpoints, exploring the abstract.

- Their radical distortion disassembled reality, inviting viewers to leap into the 20th century's unfolding uncertainty.

- By breaking old perspectives, they insisted society reflect on its breakneck change through these many-storied artistic lenses.

Dada and Surrealism

Dada emerged amidst the aftermath of World War I as a nihilistic outcry against bourgeois complacency and nationalistic ideologies. Originating in Zurich's Cabaret Voltaire, Dada was staunchly anti-art. Marcel Duchamp and Tristan Tzara eschewed traditional artist roles, sparking debates with provocative ready-mades like Duchamp's 'Fountain'—a urinal signed as art. This subversive narrative questioned the essence and value of art venues.

"Dada is a state of mind. . . . Dada applies itself to everything, and yet it is nothing, it is the point where the yes and the no and all the opposites meet, not solemnly in the castles of human philosophies, but very simply at street corners, like dogs and grasshoppers."

– Tristan Tzara3

Surrealism, rising from Dada's ashes, explored unconscious landscapes under André Breton's stewardship. Rooted in Sigmund Freud's ideas, Surrealism modeled everyday 'reality' through dream-infused canvases. Works employed startling juxtapositions and uncanny scenarios to unlock mindscapes. Salvador Dalí's 'The Persistence of Memory' conjures time warping within the psyche's depths.

Both movements embroidered critiques upon society through metaphor and ironic collapses. Dada cleared the field for Surrealism's expansion into conscious delirium. Surrealists dissected mind's manifestations, while figures like Georges Bataille weaved disruptive texts. The upheaval gestated media for feverish exploration, advancing altered digestions of cultural and inter-subjective dissonance.

Dada and Surrealism weren't merely artistic detours—they grappled with modern civilization's enigmas. By postulating artistry within psychological stretches, the movements reconceived the artist's interactions and innovated around cognition and cultural attainment.

Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art

In post-World War II America, Abstract Expressionism emerged as a visceral, paint-splattered scream, breaking from traditional forms. Artists like Jackson Pollock surveyed new frontiers of emotive depth and abstraction. Pollock's iconic 'drip paintings' indulged in intuitive flux, expressing the existential angst of an atomic age.

Pop Art, a witty rebuttal to Abstract Expressionism's intensity, embraced commercialism and popular culture. With vivid hues and ironic applications, it rejoiced in mundane familiarity while interrogating consumerist society. Andy Warhol turned everyday consumption into iconography. His Campbell's Soup Cans and celebrity silkscreens unhinged art from high culture's grasp, engaging with collective experiences echoed by media.

Both movements were vibrant counterparts within dialogues of resistance and spontaneity amidst significant socio-economic shifts.

- Abstract Expressionists smashed through depicted reality to explore emotive infinity.

- Pop Artists spotlighted intellectual depth in ubiquity.

Together, they forged pathways that thrust American art upon the global platform, renegotiating artistic value.

As the century progressed, these tides echoed a duality between tumult and tranquility, buffering state-of-the-nations' sanctities. Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art's legacy carved modern marks, shaking philosophical roosts from which future vogues would sprout amidst cultural and economical waves.

Minimalism and Postmodernism

Minimalism emerged as a serene counterpoint to the vibrant art movements of the 20th century, championing eloquence through austere aesthetic reductions. Its advocates, such as Donald Judd, espoused a creed of 'less but better,' stripping opulence to terse lines and elemental geometries.

Judd's body of work, noted for standoffish postures of wood, steel, and concrete, imbued spaces with a lacerating simplicity of dimension that cleaved through clutter and practiced profundity without contagion of noise. In Judd's celebrated works, such as his starkly utilitarian chairs and unadorned boxes arrayed in silent conversation, each item's stark purpose and essential self evolves plainly, whispered without ornament.

Minimalism advocated an aesthetic uncorrupted by indulgence, stripped back until nothing but its deeply truthful veneer remained—seen as physical, phatic touchstones to the bare bones of materiality.

Paralleling Minimalism's quiet resolve, Postmodernism drew itself up from a significant flourish of disruptive chutzpah. Contrasting with Minimalism's commitment to straightforward verity, Postmodernism embraced complexity with a delight found typically in enfant terribles—a witnessing of finery frequently wattled by a sharp and relatable wit.

Jeff Koons, Postmodernism's wily impresario, tired throngs with visual soup conversations colored with mischief well-playable in markets of contrarian wit. Koons' signature works—an alloyed fusion of vernacular panache and marketplace glean—serve as whispered bibliographies overleaped into intrigued glances; Pop machinations unboxed chic philosophic ribbits echoing their cult-pulp sermons sprawled demure by excessive normalcy before thumb wrestles unhook grandeur dashed with democratic dazzle.1

These stripped serenades orchestrate dabblings by Minimalists with thoughtful deliberations, pairing delight with Postmodernist paradoxes consistently cultivating impulses that become modular subs abruptly handing out agile credits to rewritten fluency. Minimalism and Postmodernism provide an engaging dynamic contrast on philosophical artistic engagements within the late 20th century, continually spawning pivotal debates about art's role in testing conceptual boundaries against decorative digressions.

The journey through these art movements is an engagement with the emotional and cultural currents that shaped modern artistic expression. Their legacy continues to influence contemporary art, challenging us to reflect on our perceptions and appreciate the depth of human creativity.

Key aspects of Minimalism and Postmodernism:

- Minimalism: Austerity, simplicity, and reduction

- Postmodernism: Complexity, wit, and disruption

- Contrasting approaches to artistic expression

- Influential figures: Donald Judd (Minimalism) and Jeff Koons (Postmodernism)

- Ongoing impact on contemporary art and philosophical debates